(Press-News.org) According to the traditional theory of nerves, two nerve impulses sent from opposite ends of a nerve annihilate when they collide. New research from the Niels Bohr Institute now shows that two colliding nerve impulses simply pass through each other and continue unaffected. This supports the theory that nerves function as sound pulses. The results are published in the scientific journal Physical Review X.

Nerve signals control the communication between the billions of cells in an organism and enable them to work together in neural networks. But how do nerve signals work?

Old model

In 1952, Hodgkin and Huxley introduced a model in which nerve signals were described as an electric current along the nerve produced by the flow of ions. The mechanism is produced by layers of electrically charged particles (ions of sodium and potassium) on either side of the nerve membrane that change places when stimulated. This change in charge creates an electric current.

This model has enjoyed general acceptance. For more than 60 years, all medical and biology textbooks have said that nerves function is due to an electric current along the nerve pathway. However, this model cannot explain a number of phenomena that are known about nerve function.

New model

Researchers at the Niels Bohr Institute at the University of Copenhagen have now conducted experiments that raise doubts about this well-established model of electrical impulses along the nerve pathway.

"According to the theory of this ion mechanism, the electrical signal leaves an inactive region in its wake, and the nerve can only support new signals after a short recovery period of inactivity. Therefore, two electrical impulses sent from opposite ends of the nerve should be stopped after colliding and running into these inactive regions," explains Thomas Heimburg, Professor and head of the Membrane Biophysics Group at the Niels Bohr Institute at the University of Copenhagen.

Thomas Heimburg and his research group conducted experiment in the laboratory using nerves from earthworms and lobsters. The nerves were removed and used in an experiment in which allowed the researchers to stimulate the nerve fibres with electrodes on both ends. Then they measured the signals en route.

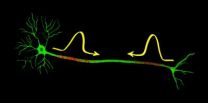

"Our study showed that the signals passed through each other completely unhindered and unaltered. That's how sound waves work. A sound wave doesn't stop when it meets another sound wave. Both waves continue on unimpeded. The nerve impulse can therefore be explained by the fact that the pulse is a mechanical wave in the form of a sound pulse, a soliton, that moves along the nerve membrane," explains Thomas Heimburg.

The theory is confirmed

When the sound pulse moves through the nerve pathway, the membrane changes locally from a liquid to a more solid form. The membrane is compressed slightly, and this change leads to an electrical pulse as a consequence of the piezoelectric effect. "The electrical signal is thus not based on an electric current but is caused by a mechanical force," points out Thomas Heimburg.

Thomas Heimburg, along with Professor Andrew Jackson, first proposed the theory that nerves function by sound pulses in 2005. Their research has since provided support for this theory, and the new experiments offer additional confirmation for the theory that nerve signals are sound pulses.

INFORMATION:

For more information contact:

Thomas Heimburg, Professor and head of the Membrane Biophysics Group at the Niels Bohr Institute, University of Copenhagen, +45 3532-5389, +45 2629-5233, theimbu@nbi.dk

Nerve impulses can collide and continue unaffected

2014-09-10

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Non-dominant hand vital to the evolution of the thumb

2014-09-10

New research from biological anthropologists at the University of Kent has shown that the use of the non-dominant hand was likely to have played a vital role in the evolution of modern human hand morphology.

In the largest experiment ever undertaken into the manipulative pressures experienced by the hand during stone tool production, researchers analysed the manipulative forces and frequency of use experienced by the thumb and fingers on the non-dominant hand during a series of stone tool production sequences that replicated early tool forms.

It is well known that ...

Living liver donors ambivalent with donation

2014-09-10

Living donors are important to increasing the number of viable grafts for liver transplantation. A new study published in Liver Transplantation, a journal of the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases and the International Liver Transplantation Society, found that ambivalence is common among donor candidates. However, providing social support may help minimize the donors' concerns regarding donation.

There is much demand for organs and a shortage of deceased organ donations. One solution to this shortage is the use of living donors for liver transplantation. ...

How skin falls apart: Pathology of autoimmune skin disease is revealed at the nanoscale

2014-09-10

BUFFALO, N.Y. –University at Buffalo researchers and colleagues studying a rare, blistering disease have discovered new details of how autoantibodies destroy healthy cells in skin. This information provides new insights into autoimmune mechanisms in general and could help develop and screen treatments for patients suffering from all autoimmune diseases, estimated to affect 5-10 percent of the U.S. population.

The research, published in PLoS One on Sept. 8, has the potential to help clinicians identify who may be at risk for developing Pemphigus vulgaris (PV), an autoimmune ...

CNIO successfully completes its fisrt clinical trial on HER-2-negative breast cancer with nintedanib

2014-09-10

The experimental drug nintedanib, combined with standard chemotherapy with paclitaxel, causes a total remission of tumours in 50% of patients suffering from early HER-2- negative breast cancer, the most common type of breast cancer. These are the conclusions of the Phase I Clinical Trial, sponsored by the Spanish National Cancer Research Centre (CNIO) and carried out by CNIO ́s Breast Cancer Clinical Research Unit. The study has been published today in British Journal of Cancer, which belongs to Nature Publishing Group.

According to Miguel Ángel Quintela, ...

Monitoring the response of bone metastases to treatment using MRI and PET

2014-09-10

Imaging technologies are very useful in evaluating a patient's response to cancer treatment, and this can be done quite effectively for most tumors using RECIST, Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors. However, RECIST works well for tumors located in soft tissue, but not so well for cancers that spread to the bone, such as is the case for prostate and breast cancers. More effort, therefore, is needed to improve our understanding of how to monitor the response of bone metastases to treatment using magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and positron emission tomography (PET), ...

'Electronic skin' could improve early breast cancer detection

2014-09-10

For detecting cancer, manual breast exams seem low-tech compared to other methods such as MRI. But scientists are now developing an "electronic skin" that "feels" and images small lumps that fingers can miss. Knowing the size and shape of a lump could allow for earlier identification of breast cancer, which could save lives. They describe their device, which they've tested on a breast model made of silicone, in the journal ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces.

Ravi F. Saraf and Chieu Van Nguyen point out that early diagnosis of breast cancer, the most common type of cancer ...

A Mexican plant could lend the perfume industry more green credibility

2014-09-10

The mere whiff of a dreamy perfume can help conjure new feelings or stir a longing for the past. But the creation of these alluring scents, from the high-end to the commonplace, can also incur an environmental toll. That could change as scientists, reporting in the journal ACS Sustainable Chemistry & Engineering, examine a more sustainable way to produce a key perfume ingredient and supply it to fragrance makers around the world.

José M. Ponce-Ortega and colleagues explain that out of the three main ingredients in perfumes, the fixatives, which allow a scent to linger ...

Unnecessary antibiotic use responsible for $163M in potentially avoidable hospital costs

2014-09-10

Arlington, Va. (September 10, 2014) – The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and Premier, Inc. have released new research on the widespread use of unnecessary and duplicative antibiotics in U.S. hospitals, which could have led to an estimated $163 million in excess costs. The inappropriate use of antibiotics can increase risk to patient safety, reduce the efficacy of these drugs and drive up avoidable healthcare costs. The study is published in the October issue of Infection Control and Hospital Epidemiology, the journal of the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology ...

Ancient swamp creature had lips like Mick Jagger

2014-09-10

DURHAM, N.C. -- Sir Mick Jagger has a new animal named after him. Scientists have named an extinct swamp-dwelling creature that lived 19 million years ago in Africa after the Rolling Stones frontman, in honor of a trait they both share -- their supersized lips.

"We gave it the scientific name Jaggermeryx naida, which translates to 'Jagger's water nymph,'" said study co-author Ellen Miller of Wake Forest University. The animal's fossilized jaw bones suggest it was roughly the size of a small deer and akin to a cross between a slender hippo and a long-legged pig.

Researchers ...

Healthcare workers wash hands more often when in presence of peers

2014-09-10

CHICAGO (September 10, 2014) – Nationally, hand hygiene adherence by healthcare workers remains staggeringly low despite its critical importance in infection control. A study in the October issue of Infection Control and Hospital Epidemiology, the journal of the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America (SHEA), found that healthcare workers' adherence to hand hygiene is better when other workers are nearby.

"Social network effects, or peer effects, have been associated with smoking, obesity, happiness and worker productivity. As we found, this influence extends ...