(Press-News.org) DURHAM, N.C. – Dangerous new pathogens such as the Ebola virus invoke scary scenarios of deadly epidemics, but even ancient scourges such as the bubonic plague are still providing researchers with new insights on how the body responds to infections.

In a study published online Sept. 18, 2014, in the journal Immunity, researchers at Duke Medicine and Duke-NUS Graduate Medical School Singapore detail how the Yersinia pestis bacteria that cause bubonic plague hitchhike on immune cells in the lymph nodes and eventually ride into the lungs and the blood stream, where the infection is easily transmitted to others.

The insight provides a new avenue to develop therapies that block this host immune function rather than target the pathogens themselves – a tactic that often leads to antibiotic resistance.

"The recent Ebola outbreak has shown how highly virulent pathogens can spread substantially and unexpectedly under the right conditions," said lead author Ashley L. St. John, Ph.D., assistant professor, Program in Emerging Infectious Diseases at Duke-NUS Singapore. "This emphasizes that we need to understand the mechanisms that pathogens use to spread so that we can be prepared with new strategies to treat infection."

While bubonic plague would seem a blight of the past, there have been recent outbreaks in India, Madagascar and the Congo. And it's mode of infection now appears similar to that used by other well-adapted human pathogens, such as the HIV virus.

In their study, the Duke and Duke-NUS researchers set out to determine whether the large swellings that are the signature feature of bubonic plague – the swollen lymph nodes, or buboes at the neck, underarms and groins of infected patients – result from the pathogen or as an immune response.

It turns out to be both.

"The bacteria actually turn the immune cells against the body," said senior author Soman Abraham, Ph.D. a professor of pathology at Duke and professor of emerging infectious diseases at Duke-NUS. "The bacteria enter the draining lymph node and actually hide undetected in immune cells, notably the dendritic cells and monocytes, where they multiply. Meanwhile, the immune cells send signals to bring in even more recruits, causing the lymph nodes to grow massively and providing a safe haven for microbial multiplication."

The bacteria are then able to travel from lymph node to lymph node within the dendritic cells and monocytes, eventually infiltrating the blood and lungs. From there, the infection can spread through body fluids directly to other people, or via biting insects such as fleas.

Abraham, St. John and colleagues note that there are several potential drug candidates that target the trafficking pathways that the bubonic plague bacteria use. In animal models, the researchers successfully used some of these therapies to prevent the bacteria from reaching systemic infection, markedly improving survival and recovery.

"This work demonstrates that it may be possible to target the trafficking of host immune cells and not the pathogens themselves to effectively treat infection and reduce mortality," St. John said. "In view of the growing emergency of multi-resistant bacteria, this strategy could become very attractive."

INFORMATION:

In addition to Abraham and St. John, study authors include W. X. Gladys Ang, Min-Nung Huang, Christian Kunder, Elizabeth W. Chan, and Michael D. Gunn.

The National Institutes of Health funded the study (R01 AI35678, R01 DK077159, R01 AI50021, R37 DK50814 and R21 AI056101).

New insights on an ancient plague could improve treatments for infections

2014-09-18

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Sensing neuronal activity with light

2014-09-18

For years, neuroscientists have been trying to develop tools that would allow them to clearly view the brain's circuitry in action—from the first moment a neuron fires to the resulting behavior in a whole organism. To get this complete picture, neuroscientists are working to develop a range of new tools to study the brain. Researchers at Caltech have developed one such tool that provides a new way of mapping neural networks in a living organism.

The work—a collaboration between Viviana Gradinaru (BS '05), assistant professor of biology and biological engineering, and ...

No sedative necessary: Scientists discover new 'sleep node' in the brain

2014-09-18

BUFFALO, N.Y. – A sleep-promoting circuit located deep in the primitive brainstem has revealed how we fall into deep sleep. Discovered by researchers at Harvard School of Medicine and the University at Buffalo School of Medicine and Biomedical Sciences, this is only the second "sleep node" identified in the mammalian brain whose activity appears to be both necessary and sufficient to produce deep sleep.

Published online in August in Nature Neuroscience, the study demonstrates that fully half of all of the brain's sleep-promoting activity originates from the parafacial ...

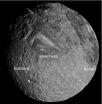

Miranda: An icy moon deformed by tidal heating

2014-09-18

Boulder, Colo., USA – Miranda, a small, icy moon of Uranus, is one of the most visually striking and enigmatic bodies in the solar system. Despite its relatively small size, Miranda appears to have experienced an episode of intense resurfacing that resulted in the formation of at least three remarkable and unique surface features -- polygonal-shaped regions called coronae.

These coronae are visible in Miranda's southern hemisphere, and each one is at least 200 km across. Arden corona, the largest, has ridges and troughs with up to 2 km of relief. Elsinore corona has ...

Research milestone in CCHF virus could help identify new treatments

2014-09-18

SAN ANTONIO, September 18, 2014 – New research into the Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever virus (CCHFV), a tick-borne virus which causes a severe hemorrhagic disease in humans similar to that caused by Ebolavirus, has identified new cellular factors essential for CCHFV infection. This discovery has the potential to lead to novel targets for therapeutic interventions against the pathogen.

The research, reported in a paper published today in the journal PLoS Pathogens and conducted by scientists at the Texas Biomedical Research Institute and their colleagues, represents ...

Microplastic pollution discovered in St. Lawrence River sediments

2014-09-18

A team of researchers from McGill University and the Quebec government have discovered microplastics (in the form of polyethylene 'microbeads', END ...

A new quality control pathway in the cell

2014-09-18

Proteins are important building blocks in our cells and each cell contains millions of different protein molecules. They are involved in everything from structural to regulatory aspects in the cell. Proteins are constructed as linear molecules but they only become functional once they are folded into specific three-dimensional structures. Several factors, like mutations, stress and age, can interfere with this folding process and induce protein misfolding. Accumulated misfolded proteins are toxic and to prevent this, cells have developed quality control systems just like ...

Small, fast, and crowded: Mammal traits amplify tick-borne illness

2014-09-18

(Millbrook, N.Y.) In the U.S., some 300,000 people are diagnosed with Lyme disease annually. Thousands also suffer from babesiosis and anaplasmosis, tick-borne ailments that can occur alone or as co-infections with Lyme disease. According to a new paper published in PLOS ONE, when small, fast-living mammals abound, so too does our risk of getting sick.

In eastern and central North America, blacklegged ticks are the primary vectors for Lyme disease, babesiosis, and anaplasmosis. The pathogens that cause these illnesses are widespread in nature; ticks acquire them when ...

Curcumin, special peptides boost cancer-blocking PIAS3 to neutralize STAT3 in mesothelioma

2014-09-18

A common Asian spice and cancer-hampering molecules show promise in slowing the progression of mesothelioma, a cancer of the lung's lining often linked to asbestos. Scientists from Case Western Reserve University and the Georg-Speyer-Haus in Frankfurt, Germany, demonstrate that application of curcumin, a derivative of the spice turmeric, and cancer-inhibiting peptides increase levels of a protein inhibitor known to combat the progression of this cancer. Their findings appeared in the Aug. 14 online edition Clinical Cancer Research; the print version of the article will ...

A new way to prevent the spread of devastating diseases

2014-09-18

For decades, researchers have tried to develop broadly effective vaccines to prevent the spread of illnesses such as HIV, malaria, and tuberculosis. While limited progress has been made along these lines, there are still no licensed vaccinations available that can protect most people from these devastating diseases.

So what are immunologists to do when vaccines just aren't working?

At Caltech, Nobel Laureate David Baltimore and his colleagues have approached the problem in a different way. Whereas vaccines introduce substances such as antigens into the body hoping ...

LSU Health research discovers means to free immune system to destroy cancer

2014-09-18

New Orleans, LA – Research led by Paulo Rodriguez, PhD, an assistant research professor of Microbiology, Immunology & Parasitology at LSU Health New Orleans' Stanley S. Scott Cancer Center, has identified the crucial role an inflammatory protein known as Chop plays in the body's ability to fight cancer. Results demonstrate, for the first time, that Chop regulates the activity and accumulation of cells that suppress the body's immune response against tumors. The LSU Health New Orleans research team showed that when they removed Chop, the T-cells of the immune system mounted ...