(Press-News.org) Princeton University researchers have developed a new method to increase the brightness, efficiency and clarity of LEDs, which are widely used on smartphones and portable electronics as well as becoming increasingly common in lighting.

Using a new nanoscale structure, the researchers, led by electrical engineering professor Stephen Chou, increased the brightness and efficiency of LEDs made of organic materials (flexible carbon-based sheets) by 58 percent. The researchers also report their method should yield similar improvements in LEDs made in inorganic (silicon-based) materials used most commonly today.

The method also improves the picture clarity of LED displays by 400 percent, compared with conventional approaches. In an article published online August 19 in the journal Advanced Functional Materials, the researchers describe how they accomplished this by inventing a technique that manipulates light on a scale smaller than a single wavelength.

"New nanotechnology can change the rules of the ways we manipulate light," said Chou, who has been working in the field for 30 years. "We can use this to make devices with unprecedented performance."

A LED, or light emitting diode, is an electronic device that emits light when electrical current moves through two terminals. LEDs offer several advantages over incandescent or fluorescent lights: they are far more efficient, compact and have a longer lifetime, all of which are important in portable displays.

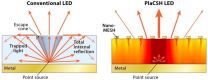

Current LEDs have design challenges; foremost among them is to reduce the amount of light that gets trapped inside the LED's structure. Although they are known for their efficiency, only a very small amount of light generated inside an LED actually escapes.

"It is exactly the same reason that lighting installed inside a swimming pool seems dim from outside – because the water traps the light," said Chou, the Joseph C. Elgin Professor of Engineering. "The solid structure of a LED traps far more light than the pool's water."

In fact, a rudimentary LED emits only about 2 to 4 percent of the light it generates. The trapped light not only makes the LEDs dim and energy inefficient, it also makes them short-lived because the trapped light heats the LED, which greatly reduces its lifespan.

"A holy grail in today's LED manufacturing is light extraction," Chou said.

Engineers have been working on this problem. By adding metal reflectors, lenses or other structures, they can increase the light extraction of LEDs. For conventional high-end, organic LEDs, these techniques can increase light extraction to about 38 percent. But these light-extraction techniques cause the display to reflect ambient light, which reduces contrast and makes the image seem hazy.

To combat the reflection of ambient light, engineers now add light-absorbing materials to the display. But Chou said such materials also absorb the light from the LED, reducing its brightness and efficiency by as much as half.

The solution presented by Chou's team is the invention of a nanotechnology structure called PlaCSH (plasmonic cavity with subwavelength hole-array). The researchers reported that PlaCSH increased the efficiency of light extraction to 60 percent, which is 57 percent higher than conventional high-end organic LEDs. At the same time, the researchers reported that PlaCSH increased the contrast (clarity in ambient light) by 400 percent. The higher brightness also relieves the heating problem caused by the light trapped in standard LEDs.

Chou said that PlaCSH is able to achieve these results because its nanometer-scale, metallic structures are able to manipulate light in a way that bulk material or non-metallic nanostructures cannot.

Chou first used the PlaCSH structure on solar cells, which convert light to electricity. In a 2012 paper, he described how the application of PlaCSH resulted in the absorption of as much as 96 percent of the light striking solar cells' surface and increased the cells' efficiency by 175 percent. Chou realized that a device that was good at absorbing light from the outside could also be good at radiating light generated inside the device – offering an efficient solution for both light extraction and the reduction of light reflection.

"From a view point of physics, a good light absorber, which we had for the solar cells, should also be a good light radiator," he said. "We wanted to experimentally demonstrate this is true in visible light range, and then use it to solve the key challenges in LEDs and displays."

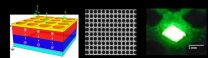

The physics behind PlaCSH are complex, but the structure is relatively simple. PlaCSH has a layer of light-emitting material about 100 nanometers thick that is placed inside a cavity with one surface made of a thin metal film. The other cavity surface is made of a metal mesh with incredibly small dimensions: it is 15 nanometers thick; and each wire is about 20 nanometers in width and 200 nanometers apart from center to center. (A nanometer is one hundred-thousandth the width of a human hair.)

Because PlaCSH works by guiding the light out of the LED, it is able to focus more of the light toward the viewer. The system also replaces the conventional brittle transparent electrode, making it far more flexible than most current displays.

"It is so flexible and ductile that it can be weaved into a cloth," Chou said.

Another benefit for manufacturers is cost. The PlaCSH organic LEDs were made by nanoimprint, a technology Chou invented in 1995, which creates nanostructures in a fashion similar to a printing press producing newspapers.

"It is cheap and extremely simple," Chou said.

Princeton has filed patent applications for both organic and inorganic LEDs using PlaCSH. Chou and his team are now conducting experiments to demonstrate PLaCSH in red and blue organic LEDs, in addition the green LEDs used in the current experiments. They also are demonstrating the system in inorganic LEDs.

INFORMATION:

Besides Chou, the paper's authors are Wei Ding, Yuxuan Wang and Hao Chen, graduate students in electrical engineering at Princeton. Support for the research was provided in part by the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency and the Office of Naval Research. Chou recently was awarded a major grant from the U.S. Department of Energy to further advance the use of PlaCSH as a solution for energy-efficient lighting.

Nanotechnology leads to better, cheaper LEDs for phones and lighting

2014-09-24

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Pressure mounts on FDA and industry to ensure safety of food ingredients

2014-09-24

Confusion over a 1997 Food and Drug Administration (FDA) rule that eases the way for food manufacturers to use ingredients "generally regarded as safe," or GRAS, has inspired a new initiative by food makers. Food safety advocates say the current GRAS process allows substances into the food supply that might pose a health risk, while industry defends its record. An article in Chemical & Engineering News (C&EN) details what changes are on the table.

Melody M. Bomgardner, a senior editor at C&EN, explains that the rule, which was never finalized, was initially established ...

Higher risk of autism found in children born at short and long interpregnancy intervals

2014-09-24

Washington D.C., September 24, 2014 – A study published in the MONTH 2014 issue of the Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry found that children who were conceived either less than 1 year or more than 5 years after the birth of their prior sibling were more likely to be diagnosed with autism than children conceived following an interval of 2-5 years.

Using data from the Finnish Prenatal Study of Autism (FIPS-A), a group of researchers led by Keely Cheslack-Postava, PhD, of Columbia University, analyzed records from 7371 children born between ...

Most breast cancer patients who had healthy breast removed at peace with decision

2014-09-24

ROCHESTER, Minn. — More women with cancer in one breast are opting to have both breasts removed to reduce their risk of future cancer. New research shows that in the long term, most have no regrets. Mayo Clinic surveyed hundreds of women with breast cancer who had double mastectomies between 1960 and 1993 and found that nearly all would make the same choice again. The findings are published in the journal Annals of Surgical Oncology.

The study made a surprising finding: While most women were satisfied with their decision whether they followed it with breast reconstruction ...

Solar explosions inside a computer

2014-09-24

The shorter the interval between two explosions in the solar atmosphere, the more likely it is that the second flare will be stronger than the first one. ETH Professor Hans Jürgen Herrmann and his team have been able to demonstrate this, using model calculations. The amount of energy released in solar flares is truly enormous – in fact, it is millions of times greater than the energy produced in volcanic eruptions. Strong explosions cause a discharge of mass from the outer part of the solar atmosphere, the corona. If a coronal mass ejection hits the earth, it can cause ...

Research shows alcohol consumption influenced by genes

2014-09-24

How people perceive and taste alcohol depends on genetic factors, and that influences whether they "like" and consume alcoholic beverages, according to researchers in Penn State's College of Agricultural Sciences.

In the first study to show that the sensations from sampled alcohol vary as a function of genetics, researchers focused on three chemosensory genes -- two bitter-taste receptor genes known as TAS2R13 and TAS2R38 and a burn receptor gene, TRPV1. The research was also the first to consider whether variation in the burn receptor gene might influence alcohol sensations, ...

Researchers identify brain areas activated by itch-relieving drug

2014-09-24

(Philadelphia, PA) – Areas of the brain that respond to reward and pleasure are linked to the ability of a drug known as butorphanol to relieve itch, according to new research led by Gil Yosipovitch, MD, Professor and Chairman of the Department of Dermatology at Temple University School of Medicine (TUSM), and Director of the Temple Itch Center. The findings point to the involvement of the brain's opioid receptors—widely known for their roles in pain, reward, and addiction—in itch relief, potentially opening up new avenues to the development of treatments for chronic itch.

The ...

New anti-cancer peptide vaccines and inhibitors developed by Ohio State Researchers

2014-09-24

COLUMBUS, Ohio – Researchers have developed two new anticancer peptide vaccines and two peptide inhibitors as part of a larger peptide immunotherapy effort at The Ohio State University Comprehensive Cancer Center – Arthur G. James Cancer Hospital and Richard J. Solove Research Institute (OSUCCC – James).

Two studies, published in the journal OncoImmunology, identify new peptide vaccines and inhibitors that target the HER-3 and IGF-1R receptors. All four agents elicited significant anti-tumor responses in human cancer cell lines and in animal models.

The studies suggest ...

Insect genomes' analysis challenges universality of essential cell division proteins

2014-09-24

Cell division, the process that ensures equal transmission of genetic information to daughter cells, has been fundamentally conserved for over a billion years of evolution. Considering its ubiquity and essentiality, it is expected that proteins that carry out cell division would also be highly conserved. Challenging this assumption, scientists from Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center have found that one of the foundational proteins in cell division, previously shown to be essential in organisms as diverse as yeast, flies and humans, has been surprisingly lost on multiple ...

'Funnel' attracts bonding partners to biomolecule

2014-09-24

Valeria Conti Nibali and Prof Dr Martina Havenith-Newen (Cluster of Excellence RESOLV – Ruhr explores Solvation) made this discovery by using a combination of terahertz absorption spectroscopy and molecular dynamics simulations. The researchers report their findings in the Journal of the American Chemical Society (JACS).

Choreography of water movements

New experimental technologies, such as terahertz absorption spectroscopy, pave the way for studies of the dynamics of water molecules surrounding biomolecules. Using this method, the researchers proved some time ago ...

States need to assume greater role in regulating dietary supplements

2014-09-24

Dietary supplements, which are marketed to adults and adolescents for weight loss and muscle building, usually do not deliver promised results and can actually cause severe health issues, including death. But because of lax federal oversight of these supplements, state governments need to increase their regulation of these products to protect consumers.

That's the finding of a new study, "The Dangerous Mix of Adolescents and Dietary Weight Loss and Muscle Building: Legal Strategies for State Action," published online Sept. 23, in the Journal of Public Health Management ...