(Press-News.org) Washington, D.C.— A team including Carnegie's Malcolm Guthrie and George Cody has, for the first time, discovered how to produce ultra-thin "diamond nanothreads" that promise extraordinary properties, including strength and stiffness greater than that of today's strongest nanotubes and polymer fibers. Such exceedingly strong, stiff, and light materials have an array of potential applications, everything from more-fuel efficient vehicles or even the science fictional-sounding proposal for a "space elevator." Their work is published in Nature Materials.

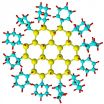

The team—led by John Badding, a chemistry professor at Penn State University and his student Thomas Fitzgibbons—used a specialized large volume high pressure device to compress benzene up to 200,000 atmospheres, at these enormous pressures, benzene spontaneously polymerizes into a long, thin strands of carbon atoms arranged just like the fundamental unit of diamond's structure—hexagonal rings of carbon atoms bonded together, but in chains rather than the full three-dimensional diamond lattice

"Because this thread is diamond at heart, we expect that it will prove to be extraordinarily stiff, extraordinarily strong, and extraordinarily useful," Badding said, explaining the long polymer threads made up of chains of carbon atoms bonded to each other, all threads being less than a nanometer in diameter.

But also, from a fundamental-science point of view, the discovery is intriguing, because "the threads we formed have a structure that has never been seen before," Badding added.

The molecule they compressed is benzene—a flat ring shaped molecule containing six carbon atoms bonded to each other and to six hydrogen atoms. After compression at high pressure, the resulting diamond-cored nanothreads are surrounded by a halo of hydrogen atoms. During the compression process, the normally flat benzene molecules stack together in a dense crystalline arrangement. As the researchers slowly release the pressure, the benzene molecules unexpectedly react with each other forming new carbon-carbon bonds with the carbon configuration of diamond extending out as a long, thin, nanothread.

The team's discovery comes after nearly a century of failed attempts by other labs to compress separate carbon-containing molecules, such as liquid benzene, into an ordered, diamond-like nanomaterial.

"We used the large high-pressure Paris-Edinburgh device at Oak Ridge National Laboratory to compress a 6-millimeter-wide amount of benzene—a gigantic amount compared with previous experiments," said Guthrie. "We discovered that slowly releasing the pressure after sufficient compression at normal room temperature gave the carbon atoms the time they needed to react with each other and to link up in a highly ordered chain of single-file carbon tetrahedrons, forming these diamond-core nanothreads."

The team is the first to coax molecules containing so-called aromatic carbon bonds to form larger scale molecular structures in the shape of long, thin nanothreads. The thread's width is phenomenally small, only a few atoms across, hundreds of thousands of times smaller than an optical fiber, and more than 20,000 times smaller than average human hair.

The scientists confirmed the structure of their diamond nanothreads using a number of advanced techniques. Parts of these first diamond nanothreads appear to be somewhat less than perfect, so improving their structure is a continuing goal the program, as is figuring out how to make the nanothreads under more-practical and larger scale conditions.

INFORMATION:

Other co-authors include En-shi Xu, Vincent Crespi, and Nasim Alem of Penn State, and Stephen Davidowski of Arizona State.

This research received financial support as part of the Energy Frontier Research in Extreme Environments (EFree) Center, and Energy Frontier Research Center funded by the U.S. Department of Energy.

The Carnegie Institution for Science is a private, nonprofit organization headquartered in Washington, D.C., with six research departments throughout the U.S. Since its founding in 1902, the Carnegie Institution has been a pioneering force in basic scientific research. Carnegie scientists are leaders in plant biology, developmental biology, astronomy, materials science, global ecology, and Earth and planetary science.

Smallest-possible diamonds form ultra-thin nanothread

2014-09-25

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Genes causing pediatric glaucoma contribute to future stroke

2014-09-25

(Edmonton, AB) Every year in Canada about 50,000 people suffer from a stroke, caused either by the interruption of blood flow or uncontrolled bleeding in the brain. While many environmental risk factors exist, including high blood pressure and smoking, stroke risk is also frequently inherited. Unfortunately, remarkably little is known regarding stroke's genetic basis.

A study from the University of Alberta, published in the Journal of Clinical Investigation, extends knowledge of stroke's genetic underpinnings and demonstrates that in some cases it originates in infancy.

The ...

Unlocking long-hidden mechanisms of plant cell division

2014-09-25

AMHERST, Mass. – Along with copying and splitting DNA during division, cells must have a way to break safely into two viable daughter cells, a process called cytokinesis. But the molecular basis of how plant cells accomplish this without mistakes has been unclear for many years.

In a new paper by cell biologist Magdalena Bezanilla of the University of Massachusetts Amherst, she and her doctoral student Shu-Zon Wu present a detailed new model that for the first time proposes how plant cells precisely position a "dynamic and complex" structure called a phragmoplast at the ...

Risk of esophageal cancer decreases with height

2014-09-25

Bethesda, MD (Sept. 25, 2014) — Taller individuals are less likely to develop esophageal cancer and it's precursor, Barrett's esophagus, according to a new study1 in Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology, the official clinical practice journal of the American Gastroenterological Association.

"Individuals in the lowest quartile of height (under 5'7" for men and 5'2" for women) were roughly twice as likely as individuals in the highest quartile of height (taller than 6' for men and 5'5" for women) to have Barrett's esophagus or esophageal cancer," said Aaron P. Thrift, ...

Putting the squeeze on quantum information

2014-09-25

CIFAR researchers have shown that information stored in quantum bits can be exponentially compressed without losing information. The achievement is an important proof of principle, and could be useful for efficient quantum communications and information storage.

Compression is vital for modern digital communication. It helps movies to stream quickly over the Internet, music to fit into digital players, and millions of telephone calls to bounce off of satellites and through fibre optic cables.

But it has not been clear if information stored in quantum bits, or qubits, ...

Looking for a spouse or a companion

2014-09-25

New Rochelle, NY, September 25, 2014—The increasing popularity of social media, online dating sites, and mobile applications for meeting people and initiating relationships has made online dating an effective means of finding a future spouse. The intriguing results of a new study that extends this comparison of online/offline meeting venues to include non-marital relationships, and explores whether break-up rates for both marital and non-marital relationships differ depending on whether a couple first met online or offline are reported in an article in Cyberpsychology, ...

World's smallest reference material is big plus for nanotechnology

2014-09-25

If it's true that good things come in small packages, then the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) can now make anyone working with nanoparticles very happy. NIST recently issued Reference Material (RM) 8027, the smallest known reference material ever created for validating measurements of these man-made, ultrafine particles between 1 and 100 nanometers (billionths of a meter) in size.

RM 8027 consists of five hermetically sealed ampoules containing one milliliter of silicon nanoparticles—all certified to be close to 2 nanometers in diameter—suspended ...

A galaxy of deception

2014-09-25

Astronomers usually have to peer very far into the distance to see back in time, and view the Universe as it was when it was young. This new NASA/ESA Hubble Space Telescope image of galaxy DDO 68, otherwise known as UGC 5340, was thought to offer an exception. This ragged collection of stars and gas clouds looks at first glance like a recently-formed galaxy in our own cosmic neighbourhood. But, is it really as young as it looks?

Astronomers have studied galactic evolution for decades, gradually improving our knowledge of how galaxies have changed over cosmic history. ...

The ideal age of sexual partners is different for men and women

2014-09-25

New evolutionary psychology research shows gender differences in age preferences regarding sexual partners.

Men and women have different preferences regarding the age of their sexual partners and women's preferences are better realized than are men's. Regarding the age of their actual sexual partners, the difference is however much smaller. Researchers in psychology at Åbo Akademi University in Turku, Finland, suggest that this pattern reflect the fact that when it comes to mating, women control the market.

Grounding their interpretation in evolutionary theory, the ...

Playing tag with sugars in the cornfield

2014-09-25

This news release is available in German. Sugars are usually known as energy storage units in plants and the insects that feed on them. But, sugars may also be part of a deadly game of tag between plant and insect according to scientists at the Max Planck Institute for Chemical Ecology. Grasses and crops such as maize attach sugars to chemical defenses called benzoxazinoids to protect themselves from being poisoned by their own protective agents. Then, when an insect starts feeding, a plant enzyme removes the sugar to deploy the active toxin. The Max Planck scientists ...

Brazilian zoologists discovered the first obligate cave-dwelling flatworm in South America

2014-09-25

Typical cave-dwelling organisms, unpigmented and eyeless, were discovered in a karst area located in northeastern Brazil. The organisms were assigned to a new genus and species of freshwater flatworm and may constitute an oceanic relict. They represent the first obligate cave-dwelling flatworm in South America. The study was published in the open access journal ZooKeys.

Freshwater flatworms occur on a wide range of habitats, namely streams, lagoons, ponds, among others. Some species also occur in subterranean freshwater environments.

Brazil has more than 11,000 caves, ...