(Press-News.org) Putnam Valley, NY. (Oct. 13, 2014) – Two studies recently published in Cell Transplantation reveal that cell transplantation may be an effective treatment for spinal cord injury (SCI), a major cause of disability and paralysis with no current restorative therapies.

Using laboratory rats modeled with SCI, researchers in Spain found in laboratory tests on cells harvested from rats - specifically ependymal progenitor cells (epSPCs), multipotent stem cells found in adult tissues surrounding the ependymal canal of the spinal cord - responded to a variety of compounds through the activation of purinergic receptors P2X4, P2X7, P2Y1 and P2Y4. In addition, the epSPCs responded to adenosine triphosphate (ATP) through this activation. ATP, a chemical produced by a wide variety of enzymes that works to transport energy within cells, is known to accumulate at the sites of spinal cord injury and cooperate with growth factors that induce remodeling and repair.

"The aim of our study was to analyze the expression profile of receptors in ependymal-derived neurospheres and to determine which receptors were functional by analysis of intercellular Ca2+ concentration," said study co-author Dr. Rosa Gomez-Villafuertes of the Department of Biochemistry at the Veterinary School at the University of Complutense in Madrid, Spain. "We demonstrated for the first time that epSPCs express functional ionotropic P2X4 and P2X7 and metabotropic P2Y1 and P2Y4 receptors that are able to respond to ATP, ADP and other nucleotide compounds."

When they compared the epSPCs from healthy rats to epSPCs from rats modeled with SCI, they found that a downregulation of P2Y1 and an upregulation of P2Y4 had occurred in the epSPCs in the SCI group.

"This finding opens an important avenue for potential therapeutic alternatives in SCI treatments based on purinergic receptor modulation," the researchers concluded.

INFORMATION:

The study will be published in a future issue of Cell Transplantation and is currently freely available on-line as an unedited early e-pub at: http://www.ingentaconnect.com/content/cog/ct/pre-prints/content-CT-1257_Gomez_Villafuertes.

Contact: Dr. Rosa Gomez-Villafeurtes, Department of Biochemistry, Veterinary School, University of Complutense, Av. Puerta de Hierro s/n, 28040, Madrid, Spain.

Email: marosa@vet.ucm.es

Ph: +34913943890

Fax: + 34913943909

Citation: Gómez-Villafuertes, R.; Rodríguez-Jiménez, F. J.; Alastrue-Agudo, A.; Stojkovic, M.; Miras-Portugal, M. T.; Moreno-Manzano, V. Purinergic receptors in spinal cord-derived ependymal stem/progenitor cells and its potential role in cell-based therapy for spinal cord injury. Cell Transplant.

Appeared or available online: July 15, 2014

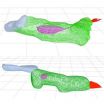

Spinal cord injury results in demyelination of surviving axons and impairment of motor and sensory function. In a second study on cell transplantation and SCI, a combined Egyptian/U.S. research team from Cairo University and Rutgers University's Robert Wood Johnson Medical School discovered that transplanted and manipulated adherent, autologous (self-donated) bone marrow cells (ABMCs), when transplanted into dogs modeled with SCI, augmented the remyelination process and enhanced neurological repair of the damaged area. They used bone marrow cells because bone marrow is known to contain multiple cell types that contribute differently to injury repair.

"Our study demonstrated that the transplantation of autologous canine ABMCs contributed considerably to the inadequate axonal regeneration resulting from SCI," said Dr. Hatem E. Sabaawy of the Regenerative and Molecular Medicine Program at the Robert Wood Johnson Medical School at Rutgers University. "These data were in accordance with the beneficial effects seen with ABMC transplantation in humans with SCI as based on the outcome of our Phase I/II clinical trial."

The researchers noted that it was possible that ABMCs or their derivative cells are reprogrammed in the body (in vivo) to adapt to or exhibit a remyelinating fate "in response to clues in the SCI microenvironment."

"Further studies of each of these potential mechanisms of repair will shed light on the roles of ABMCs in mediating SCI repair and allow for defining targets for an added enhancement of these repair features to achieve a more significant neural regeneration," they concluded.

The study will be published in a future issue of Cell Transplantation and is currently freely available on-line as an unedited early e-pub at: http://www.ingentaconnect.com/content/cog/ct/pre-prints/content-CT-0904_Gabr.

Contact: Dr. Hatem E. Sabaawy, Regenerative and Molecular Medicine Program, Robert Wood Johnson School of Medicine, Rutgers University. 195 Little Albany St., New Brunswick, NJ 08901, USA.

Email: sabaawhe@rutgers.edu

Ph: 732-235-8081

Fax: 732-235-8681

Citation: Gabr, H.; El-kheir, W. A.; Farghali, H. A. M. A.; Ismail, Z. M. K.; Zickri, M. B.; El Maadawi, Z. M.; Kishk, N. A.; Sabaawy, H. E. Intrathecal transplantation of autologous adherent bone marrow cells induces functional neurological recovery in a canine model of spinal cord injury. Cell Transplant.

Appeared or available online: July 15, 2014

"These two studies highlight the increasing evidence demonstrating that a variety of different types of stem cells could have benefit in the treatment of spinal cord injury" said Dr. Shinn-Zong Lin, professor of Neurosurgery and superintendent at the China Medical University Hospital, Beigang, Taiwan and Coeditor-in-chief of Cell Transplantation. "The first study highlights a potentially important role of purinergic receptors and neural stem cells in regenerative therapy, while the second study demonstrates benefit using autologous bone marrow cells that can be relatively easily obtained in a larger animal model than rodents."

INFORMATION:

The Coeditors-in-chief for CELL TRANSPLANTATION are at the Diabetes Research Institute, University of Miami Miller School of Medicine and Center for Neuropsychiatry, China Medical University Hospital, TaiChung, Taiwan. Contact, Camillo Ricordi, MD at ricordi@miami.edu or Shinn-Zong Lin, MD, PhD at shinnzong@yahoo.com.tw or David Eve, PhD at celltransplantation@gmail.com

News release by Florida Science Communications http://www.sciencescribe.net

Spinal cord injury victims may benefit from stem cell transplantation studies

Two studies provide positive results and provide hope for future patients

2014-10-14

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Treating cancer: UI biologists find gene that could stop tumors in their tracks

2014-10-14

The dirt in your backyard may hold the key to isolating cancerous tumors and to potential new treatments for a host of cancers.

University of Iowa researchers have found a gene in a soil-dwelling amoeba that functions similarly to the main tumor-fighting gene found in humans, called PTEN.

When healthy, PTEN suppresses tumor growth in humans. But the gene is prone to mutate, allowing cancerous cells to multiply and form tumors. PTEN mutations are believed to be involved in 40 percent of breast cancer cases, up to 70 percent of prostate cancer cases, and nearly half of ...

How metastases develop in the liver

2014-10-14

This news release is available in German. In order to invade healthy tissue, tumor cells must leave the actual tumor and enter the bloodstream or lymphatic system. For this purpose, they use certain enzymes, proteases that break down the tissue surrounding the tumor, thus opening the way for tumor cells to reach blood or lymphatic vessels. To keep the proteases in check, the body produces inhibitors such as the protein TIMP-1, which thwart the proteases in their work.

But during development of metastases, the control function of this inhibitor appears not only to ...

Size of minority population impacts states' prison rates, Baker Institute researcher finds

2014-10-14

HOUSTON – (Oct. 13, 2014) – New research from Rice University's Baker Institute for Public Policy found that states with a large minority population tend to incarcerate more people.

According to lead author Katharine Neill, states with large African-American populations are more likely to have harsher incarceration practices, worse conditions of confinement and tougher policies toward juveniles compared with other states. She said these findings provide some support for long-standing arguments among sociology and criminal justice experts that the criminal ...

Uncertain reward more motivating than sure thing, study finds

2014-10-14

Recently, uncertainty has been getting a bad rap. Hundreds of articles have been printed over the last few years about how uncertainty brings negative effects to the markets and creates a drag on the economy at large. But a new study appearing in the February 2015 edition of the Journal of Consumer Research finds that uncertainty can be motivating.

In "The Motivating-Uncertainty Effect: Uncertainty Increases Resource Investment in the Process of Reward Pursuit," Professors Ayelet Fishbach and Christopher K. Hsee of the University of Chicago Booth School of Business and ...

Inside the Milky Way

2014-10-14

Is matter falling into the massive black hole at the center of the Milky Way or being ejected from it? No one knows for sure, but a UC Santa Barbara astrophysicist is searching for an answer.

Carl Gwinn, a professor in UCSB's Department of Physics, and colleagues have analyzed images collected by the Russian spacecraft RadioAstron. Their findings appear in the current issue of The Astrophysical Journal Letters.

RadioAstron was launched into orbit from Baikonur, Kazakhstan, in July 2011 with several missions, one of which was to investigate the scattering of pulsars ...

PTPRZ-MET fusion protein: A new target for personalized brain cancer treatment

2014-10-14

Researchers at the University of California, San Diego School of Medicine have identified a new fusion protein found in approximately 15 percent of secondary glioblastomas or brain tumors. The finding offers new insights into the cause of this cancer and provides a therapeutic target for personalized oncologic care. The findings were published this month in the online edition of Genome Research.

Glioblastoma is the most common and deadliest form of brain cancer. The majority of these tumors – known as primary glioblastomas – occur in the elderly without evidence ...

Researchers say academia can learn from Hollywood

2014-10-14

HOUSTON, Oct. 13, 2014 – According to a pair of University of Houston (UH) professors and their Italian colleague, while science is increasingly moving in the direction of teamwork and interdisciplinary research, changes need to be made in academia to allow for a more collaborative model to flourish.

Professors Ioannis T. Pavlidis and Ioanna Semendeferi from UH and Alexander M. Petersen from the IMT Lucca Institute for Advanced Studies in Italy published a commentary in the October 2014 issue of Nature Physics, articulating policies that will harmonize academic ...

University of Tennessee study finds crocodiles are sophisticated hunters

2014-10-14

Recent studies have found that crocodiles and their relatives are highly intelligent animals capable of sophisticated behavior such as advanced parental care, complex communication and use of tools for hunting.

New University of Tennessee, Knoxville, research published in the journal Ethology Ecology and Evolution shows just how sophisticated their hunting techniques can be.

Vladimir Dinets, a research assistant professor in UT's Department of Psychology, has found that crocodiles work as a team to hunt their prey. His research tapped into the power of social media ...

Out-of-step cells spur muscle fibrosis in Duchenne muscular dystrophy patients

2014-10-14

AUDIO:

A study in The Journal of Cell Biology suggests that asynchronous regeneration of cells within muscle tissue leads to the development of fibrosis in patients with Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Listen...

Click here for more information.

Like a marching band falling out of step, muscle cells fail to perform in unison in patients with Duchenne muscular dystrophy. A new study in The Journal of Cell Biology reveals how this breakdown leads to the proliferation of stiff fibrotic ...

University of Calgary research leads to brain cancer clinical trial

2014-10-14

Researchers at the University of Calgary's Hotchkiss Brain Institute (HBI) and Southern Alberta Cancer Research Institute (SACRI) have made a discovery that could prolong the life of people living with glioblastoma – the most aggressive type of brain cancer. Samuel Weiss, PhD, Professor and Director of the HBI, and Research Assistant Professor Artee Luchman, PhD, and colleagues, published their work today in Clinical Cancer Research, which is leading researchers to start a human phase I/II clinical trial as early as Spring 2015.

Researchers used tumour cells derived ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

A shift from the sandlot to the travel team for youth sports

Hair-width LEDs could replace lasers

The hidden infections that refuse to go away: how household practices can stop deadly diseases

Ochsner MD Anderson uses groundbreaking TIL therapy to treat advanced melanoma in adults

A heatshield for ‘never-wet’ surfaces: Rice engineering team repels even near-boiling water with low-cost, scalable coating

Skills from being a birder may change—and benefit—your brain

Waterloo researchers turning plastic waste into vinegar

Measuring the expansion of the universe with cosmic fireworks

How horses whinny: Whistling while singing

US newborn hepatitis B virus vaccination rates

When influencers raise a glass, young viewers want to join them

Exposure to alcohol-related social media content and desire to drink among young adults

Access to dialysis facilities in socioeconomically advantaged and disadvantaged communities

Dietary patterns and indicators of cognitive function

New study shows dry powder inhalers can improve patient outcomes and lower environmental impact

Plant hormone therapy could improve global food security

A new Johns Hopkins Medicine study finds sex and menopause-based differences in presentation of early Lyme disease

Students run ‘bee hotels’ across Canada - DNA reveals who’s checking in

SwRI grows capacity to support manufacture of antidotes to combat nerve agent, pesticide exposure in the U.S.

University of Miami business technology department ranked No. 1 in the nation for research productivity

Researchers build ultra-efficient optical sensors shrinking light to a chip

Why laws named after tragedies win public support

Missing geomagnetic reversals in the geomagnetic reversal history

EPA criminal sanctions align with a county’s wealth, not pollution

“Instead of humans, robots”: fully automated catalyst testing technology developed

Lehigh and Rice universities partner with global industry leaders to revolutionize catastrophe modeling

Engineers sharpen gene-editing tools to target cystic fibrosis

Pets can help older adults’ health & well-being, but may strain budgets too

First evidence of WHO ‘critical priority’ fungal pathogen becoming more deadly when co-infected with tuberculosis

World-first safety guide for public use of AI health chatbots

[Press-News.org] Spinal cord injury victims may benefit from stem cell transplantation studiesTwo studies provide positive results and provide hope for future patients