(Press-News.org) Berkeley — Scientists at the University of California, Berkeley, have taken proteins from nerve cells and used them to create a "smart" material that is extremely sensitive to its environment. This marriage of materials science and biology could give birth to a flexible, sensitive coating that is easy and cheap to manufacture in large quantities.

The work, to be published Tuesday, Oct. 14, in the journal Nature Communications, could lead to new types of biological sensors, flow valves and controlled drug release systems, the researchers said. Biomedical applications include microfluidic devices that can handle and process very small volumes of liquid, such as samples of saliva or blood, for diagnostics.

"This work represents a unique convergence of the fields of biomimetic materials, biomolecular engineering and synthetic biology," said principal investigator Dr. Sanjay Kumar, UC Berkeley associate professor of bioengineering. "We created a new class of smart, protein-based materials whose structural principles are inspired by networks found in living cells."

Kumar's research team set out to create a biological version of a synthetic coating used in everyday liquid products, such as paint and liquid cosmetics, to keep small particles from clumping together. The synthetic coatings are often called polymer brushes because of their bristle-like appearance when attached to the particle surface.

To create the biological equivalent of a polymer brush, the researchers turned to neurofilaments, pipe cleaner-shaped proteins found in nerve cells. By acting as tiny, cylindrical polymer brushes, neurofilaments collectively assemble into a structural network that helps keep one end of the nerve cell propped open so that it can conduct electrical signals.

"We co-opted this protein and turned it into a polymer brush by cloning a portion of a gene that encodes one of the neurofilament bristles, re-engineering it such that we could attach the resulting protein to surfaces in a precise and oriented way, and then expressing the gene in bacteria to produce the protein in large, pure quantities," said Kumar. "We showed that our 'protein brush' had all the key properties of synthetic brushes, plus a number of advantages."

Kumar noted that neurofilaments are good candidates for protein brushes because they are intrinsically disordered proteins, so named because they don't have a fixed 3-D shape. The size and chemical sequence of these hair-like proteins are far easier to control when compared with their synthetic counterparts.

"In biology, precision is critical," said Kumar. "Proteins are generally synthesized with the exact same sequence every time; the length and biochemical order of the protein sequence affects all of its properties, including structure and the ability to bind to other molecules and catalyze biochemical reactions. This kind of sequence precision is difficult if not impossible to achieve in the laboratory using the tools of chemical synthesis. By harnessing the precision of biology and letting the bacterial cell do all the work for us, we were able to control the exact length and sequence of the bristles of our protein brush."

The researchers showed that the protein brushes could be grafted onto surfaces, and that they dramatically expand and collapse in reaction to changes in acidity and salinity. Materials that are environmentally sensitive in this way are often referred to as "smart" materials because of their ability to adaptively respond to specific stimuli.

INFORMATION:

Other co-authors on the paper are Nithya Srinivasan, Maniraj Bhagawati, and Badriprasad Ananthanarayanan, all of whom are postdoctoral fellows in Kumar's lab.

This work was supported by a Presidential Early Career Award for Scientists and Engineers from the Army Research Office and a Hellman Faculty Fund Award, both given to Kumar.

Scientists create new protein-based material with some nerve

2014-10-14

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Feeling guilty or ashamed? Think about your emotions before you shop

2014-10-14

Suppose you grabbed a few cookies before heading out to the grocery store and start to feel guilty or ashamed about breaking your diet. According to a new study in the Journal of Consumer Research, feeling guilty might find you comparing calories in different cartons of ice cream. Feeling ashamed might keep you from buying any ice cream in the first place.

"We examined the emotions of guilt and shame and found that when consumers feel guilty, they tend to focus on concrete details at the expense of the bigger picture. On the other hand, when consumers feel ashamed, they ...

Marketing an innovative new product? An exciting product launch could hurt sales

2014-10-14

Should every successful product launch involve some sort of dazzling spectacle? A new study in the Journal of Consumer Research tells us that this might be a great way to market an upgrade, but a flashy launch could backfire if a new product is truly innovative.

"The accepted wisdom is that consumers get excited about new and unique products they cannot immediately understand. However, these feelings of excitement can quickly change to tension and anxiety if we can't ultimately make sense of what a product does, especially if we are in a stimulating retail environment," ...

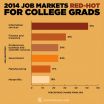

Jobs plentiful for college grads

2014-10-14

EAST LANSING, Mich. — The job market for new college graduates is red hot.

After several years of modest growth, hiring is expected to jump a whopping 16 percent for newly minted degree-holders in 2014-15, according to key findings from Recruiting Trends. The annual survey, by Michigan State University economist Phil Gardner, is the nation's largest with nearly 5,700 companies responding.

"Employers are recruiting new college graduates at levels not seen since the dot-com frenzy of 1999-2000," said Gardner, director of MSU's Collegiate Employment Research Institute. ...

New light on the 'split peak' of alcohols

2014-10-14

WASHINGTON D.C., October 14, 2014 -- For scientists probing the electronic structure of materials using a relatively new technique called resonant inelastic soft X-ray scattering (RIXS) in the last few years, a persistent question has been how to account for "split peak" spectra seen in some hydrogen-bonded materials.

In RIXS, low-energy X-rays from synchrotron or X-ray free-electron laser light sources scatter off molecules within the studied material. If those molecules include light elements, such as the -OH group in alcohols, the complex spectra RIXS produces are ...

Protein found in insect blood that helps power pests' immune responses

2014-10-14

MANHATTAN, Kansas — Pest insects may be sickened to learn to that researchers at Kansas State University have discovered a genetic mechanism that helps compromise their immune system.

Michael Kanost, university distinguished professor of biochemistry and molecular biophysics, led a study by Kansas State University researchers that looked at how protein molecules in the blood of insects function in insects' immune system. Insects use proteins that bind to the surface of pathogens to detect infections in their body.

"For example, when a mosquito transmits a pathogen ...

The Costco effect: Do consumers buy less variety at bigger stores?

2014-10-14

Do consumers make the same choices when products such as beer, soft drinks, or candy bars are sold individually or in bundles? According to a new study in the Journal of Consumer Research, consumers purchase a greater variety of products when they are packaged individually rather than bundled together.

"When consumers choose multiple products, they are influenced by the mere mechanics of choosing, regardless of their product preference. Consumers are more likely to seek variety when choosing from single rather than bundled products," write authors Mauricio Mittelman (Universidad ...

Study exposes bias in transportation system design

2014-10-14

DENVER (Oct. 14, 2014) – America's streets are designed and evaluated with a an inherent bias toward the needs of motor vehicles, ignoring those of bicyclists, pedestrians, and public transit users, according to a new study co-authored by Wesley Marshall of the University of Colorado Denver.

"The most common way to measure transportation performance is with the level-of-service standard," said Marshall, PhD, PE, assistant professor of civil engineering at the CU Denver College of Engineering and Applied Science, the top public research university in Denver. "But ...

Defective gene renders diarrhoea vaccine ineffective

2014-10-14

Every year rotavirus causes half a million diarrhoea-related deaths amongst children in developing countries. Existing vaccines provide poor protection. The reason could be a widespread genetic resistance amongst children, according to virologists at Linköping University.

Acute diarrhoeal illnesses cause nearly one-fifth of all child deaths in developing countries. The most common cause is rotavirus. Improved sanitation and hygiene have had a limited effect on the spread of the illness. Today, vaccination is considered the most important method for reducing mortality. ...

Common gene variants linked to delayed healing of bone fractures

2014-10-14

Slow-healing or non-healing bone fractures in otherwise healthy people may be caused by gene variants that are common in the population, according to Penn State College of Medicine researchers.

"We found associations between certain gene polymorphisms and delayed fracture healing in a sample of patients," said J. Spence Reid, professor of orthopaedics and rehabilitation. "Our study was preliminary but it demonstrated the feasibility of a larger one, which we're now working to set up."

The identification of gene variants that delay fracture healing could lead to screening ...

Precise control over genes results from game-changing research

2014-10-14

The application of a new, precise way to turn genes on and off within cells, described online October 9, 2014 in two articles in the journal Cell, is likely to lead to a better understanding of diseases and possibly to new therapies, according to UC San Francisco scientists.

The key to the advance is a new invention, called the SunTag, a series of molecular hooks for hanging multiple copies of biologically active molecules onto a single protein scaffold used to target genes or other molecules. Compared to molecules assembled without these hooks, those incorporating the ...