(Press-News.org) VIDEO:

Michael Helmrath, M.D., M.S., surgical director of the Intestinal Rehabilitation Program at Cincinnati Children's Hospital Medical Center, talks about researchers successfully growing human intestinal tissue in mice. The study describes...

Click here for more information.

CINCINNATI --Researchers have successfully transplanted "organoids" of functioning human intestinal tissue grown from pluripotent stem cells in a lab dish into mice – creating an unprecedented model for studying diseases of the intestine.

Reporting their results Oct. 19 online in Nature Medicine, scientists from Cincinnati Children's Hospital Medical Center said that, through additional translational research the findings could eventually lead to bioengineering personalized human intestinal tissue to treat gastrointestinal diseases.

"These studies support the concept that patient-specific cells can be used to grow intestine," said Michael Helmrath, MD, MS, lead investigator and surgical director of the Intestinal Rehabilitation Program at Cincinnati Children's. "This provides a new way to study the many diseases and conditions that can cause intestinal failure, from genetic disorders appearing at birth to conditions that strike later in life, such as cancer and Crohn's disease. These studies also advance the longer-term goal of growing tissues that can replace damaged human intestine."

The scientists used induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) – which can become any tissue type in the body – to generate the intestinal organoids. The team converted adult cells drawn from skin and blood samples into "blank" iPSCs, then placed the stem cells into a specific molecular cocktail so they would form intestinal organoids.

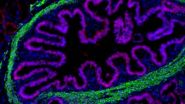

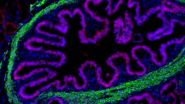

The human organoids were then engrafted into the capsule of the kidney of a mouse, providing a necessary blood supply that allowed the organoid cells to grow into fully mature human intestinal tissue. The researchers noted that this step represents a major sign of progress for a line of regenerative medicine that scientists worldwide have been working for several years to develop.

Mice used in the study were genetically engineered so their immune systems would accept the introduction of human tissues. The grafting procedure required delicate surgery at a microscopic level, according to researchers. But once attached to a mouse's kidney, the study found that the cells grow and multiply on their own. Each mouse in the study produced significant amounts of fully functional, fully human intestine.

"The mucosal lining contains all the differentiated cells and continuously renews itself by proliferation of intestinal stem cells. In addition, the mucosa develops both absorptive and digestive ability that was not evident in the culture dish," Helmrath said. "Importantly, the muscle layers of the intestine also develop."

What This Means for Patients

The new findings eventually could be good news for people born with genetic defects affecting their digestive systems or people who have lost intestinal function from cancer, as well as Crohn's disease and other related inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD).

One of the advantages of using tissue generated from iPSCs is that the treatment process would involve the patient's own tissue, thus eliminating the risk and expense of life-long medications to prevent transplant rejection.

However, the researchers cautioned that it will take years of further research to translate lab-grown tissue replacement into medical practice. In the meantime, the discovery could have other, more immediate benefits by accelerating drug development and the concept of personalized medicine.

The current process for developing new medications depends on a long and imperfect process of animal testing. Promising compounds from the lab are tested in animals bred to mimic human diseases and conditions. Many compounds that prove effective and safe in mice turn out to be unsuccessful in human clinical trials. Others have mixed results, where some groups of patients clearly benefit from the new drug, but others suffer harmful side effects.

Lab-grown organoids have the potential to replace much of the animal testing stage by allowing early drug research to occur directly upon human tissue. Going straight to human tissue testing could shave years off the drug development process, researchers said.

The current study in Nature represents the latest step in years of stem cell and organoid research at Cincinnati Children's, much of which has been led by James Wells, PhD, and Noah Shroyer, PhD. Wells is a scientist in the divisions of Developmental Biology and Endocrinology at Cincinnati Children's and director of the Pluripotent Stem Cell Center. Shroyer is a scientist in the divisions of Gastroenterology, Hepatology & Nutrition and Developmental Biology.

Wells and colleagues first reported success at growing intestinal organoids in the lab in December 2010. Since then, the team has reported similar success at growing organoids of stomach tissue.

Also collaborating were researchers at the Department of Internal Medicine, University of Michigan (Ann Arbor, Mich.)

INFORMATION:

Funding support for the study came in part from: the National Institutes of Health (DK092456; U18NS080815; R01DK098350; DK092306; CA142826; R01DK083325; P30 DK078392; UL1RR026314; K01DK091415 P30DK034933; DK094775).

About Cincinnati Children's:

Cincinnati Children's Hospital Medical Center ranks third in the nation among all Honor Roll hospitals in U.S. News and World Report's 2014 Best Children's Hospitals. It is also ranked in the top 10 for all 10 pediatric specialties. Cincinnati Children's, a non-profit organization, is one of the top three recipients of pediatric research grants from the National Institutes of Health, and a research and teaching affiliate of the University of Cincinnati College of Medicine. The medical center is internationally recognized for improving child health and transforming delivery of care through fully integrated, globally recognized research, education and innovation. Additional information can be found at http://www.cincinnatichildrens.org. Connect on the Cincinnati Children's blog, via Facebook and on Twitter.

DNA has garnered attention for its potential as a programmable material platform that could spawn entire new and revolutionary nanodevices in computer science, microscopy, biology, and more. Researchers have been working to master the ability to coax DNA molecules to self assemble into the precise shapes and sizes needed in order to fully realize these nanotechnology dreams.

For the last 20 years, scientists have tried to design large DNA crystals with precisely prescribed depth and complex features – a design quest just fulfilled by a team at Harvard's Wyss Institute ...

AMHERST, Mass. ¬– The claim by microbiologist Derek Lovley and colleagues at the University of Massachusetts Amherst that the microbe Geobacter produces tiny electrical wires, called microbial nanowires, has been mired in controversy for a decade, but the researchers say a new collaborative study provides stronger evidence than ever to support their claims.

UMass Amherst physicists working with Lovley and colleagues report in the current issue of Nature Nanotechnology that they've used a new imaging technique, electrostatic force microscopy (EFM), to resolve ...

Berlin, 19th October 2014 What's in a name? Doctors have found that the name of the drug you are prescribed significantly influences how the patient sees the treatment. Now in a significant shift, the world's major psychiatry organisations are proposing to completely change the terminology of the drugs used in mental disorders shifting it from symptom based (e.g. antidepressant, antipsychotic etc.) to pharmacologically based (e.g. focusing on pharmacological target (serotonin, dopamine etc.) and the relevant mode of action). This will mean that patient will no longer have ...

Scientists at The University of Manchester hope a major breakthrough could lead to more effective methods for detoxifying dangerous pollutants like PCBs and dioxins. The result is a culmination of 15 years of research and has been published in Nature. It details how certain organisms manage to lower the toxicity of pollutants.

The team at the Manchester Institute of Biotechnology were investigating how some natural organisms manage to lower the level of toxicity and shorten the life span of several notorious pollutants.

Professor David Leys explains the research: ...

Kansas City, MO - While megakaryocytes are best known for producing platelets that heal wounds, these "mega" cells found in bone marrow also play a critical role in regulating stem cells according to new research from the Stowers Institute for Medical Research. In fact, hematopoietic stem cells differentiate to generate megakaryocytes in bone marrow. The Stowers study is the first to show that hematopoietic stem cells (the parent cells) can be directly controlled by their own progeny (megakaryocytes).

The findings from the lab Stowers Investigator Linheng Li, Ph.D., described ...

At least 2 percent of people over age 40 and 5 percent of people over 70 have mutations linked to leukemia and lymphoma in their blood cells, according to new research at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis.

Mutations in the body's cells randomly accumulate as part of the aging process, and most are harmless. For some people, genetic changes in blood cells can develop in genes that play roles in initiating leukemia and lymphoma even though such people don't have the blood cancers, the scientists report Oct. 19 in Nature Medicine.

The findings, based ...

CHICAGO – Oct. 19, 2014 – The first tear duct implant developed to treat inflammation and pain following cataract surgery has been shown to be a reliable alternative to medicated eye drops, which are the current standard of care, according to a study presented today at AAO 2014, the 118th annual meeting of the American Academy of Ophthalmology. The device, known as a punctum plug, automatically delivers the correct amount of postoperative medication in patients, potentially solving the issue of poor compliance with self-administering eye drops.

After cataract ...

BETHESDA, MD – A child's genetic makeup may contribute to his or her mother's risk of rheumatoid arthritis, possibly explaining why women are at higher risk of developing the disease than men. This research will be presented Tuesday, October 21, at the American Society of Human Genetics (ASHG) 2014 Annual Meeting in San Diego.

Rheumatoid arthritis, a painful inflammatory condition that primarily affects the joints, has been tied to a variety of genetic and environmental factors, including lifestyle factors and previous infections. Women are three times more likely ...

BETHESDA, MD – Scientists studying birth defects in humans and purebred dogs have identified an association between cleft lip and cleft palate – conditions that occur when the lip and mouth fail to form properly during pregnancy – and a mutation in the ADAMTS20 gene. Their findings were presented today at the American Society of Human Genetics (ASHG) 2014 Annual Meeting in San Diego.

"These results have potential implications for both human and animal health, by improving our understanding of what causes these birth defects in both species," said Zena ...

Geneva, Switzerland – 19 October 2014: Women are more likely to develop anxiety and depression after a heart attack (myocardial infarction; MI) than men, according to research presented at Acute Cardiovascular Care 2014 by Professor Pranas Serpytis from Lithuania.

Acute Cardiovascular Care is the annual meeting of the Acute Cardiovascular Care Association (ACCA) of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and takes place 18-20 October in Geneva, Switzerland.

Professor Serpytis said: "The World Health Organization predicts that by 2020 depression will be the second ...