Researchers from Princeton University and the University of California-San Diego (UCSD) recently found that an immune-system protein called MHCI, or major histocompatibility complex class I, moonlights in the nervous system to help regulate the number of synapses, which transmit chemical and electrical signals between neurons. The researchers report in the Journal of Neuroscience that in the brain MHCI could play an unexpected role in conditions such as Alzheimer's disease, type II diabetes and autism.

MHCI proteins are known for their role in the immune system where they present protein fragments from pathogens and cancerous cells to T cells, which are white blood cells with a central role in the body's response to infection. This presentation allows T cells to recognize and kill infected and cancerous cells.

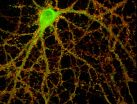

In the brain, however, the researchers found that MHCI immune molecules are one of the only known factors that limit the density of synapses, ensuring that synapses form in the appropriate numbers necessary to support healthy brain function. MHCI limits synapse density by inhibiting insulin receptors, which regulate the body's sugar metabolism and, in the brain, promote synapse formation.

Senior author Lisa Boulanger, an assistant professor in the Department of Molecular Biology and the Princeton Neuroscience Institute (PNI), said that MHCI's role in ensuring appropriate insulin signaling and synapse density raises the possibility that changes in the protein's activity could contribute to conditions such Alzheimer's disease, type II diabetes and autism. These conditions have all been associated with a complex combination of disrupted insulin-signaling pathways, changes in synapse density, and inflammation, which activates immune-system molecules such as MHCI.

Patients with type II diabetes develop "insulin resistance" in which insulin receptors become incapable of responding to insulin, the reason for which is unknown, Boulanger said. Similarly, patients with Alzheimer's disease develop insulin resistance in the brain that is so pronounced some have dubbed the disease "type III diabetes," Boulanger said.

"Our results suggest that changes in MHCI immune proteins could contribute to disorders of insulin resistance," Boulanger said. "For example, chronic inflammation is associated with type II diabetes, but the reason for this link has remained a mystery. Our results suggest that inflammation-induced changes in MHCI could have consequences for insulin signaling in neurons and maybe elsewhere."

MHCI levels also are "dramatically altered" in the brains of people with Alzheimer's disease, Boulanger said. Normal memory depends on appropriate levels of MHCI. Boulanger was senior author on a 2013 paper in the journal Learning and Memory that found that mice bred to produce less functional MHCI proteins exhibited striking changes in the function of the hippocampus, a part of the brain where some memories are formed, and had severe memory impairments.

"MHCI levels are altered in the Alzheimer's brain, and altering MHCI levels in mice disrupts memory, reduces synapse number and causes neuronal insulin resistance, all of which are core features of Alzheimer's disease," Boulanger said.

Links between MHCI and autism also are emerging, Boulanger said. People with autism have more synapses than usual in specific brain regions. In addition, several autism-associated genes regulate synapse number, often via a signaling protein known as mTOR (mammalian target of rapamycin). In their study, Boulanger and her co-authors found that mice with reduced levels of MHCI had increased insulin-receptor signaling via the mTOR pathway, and, consequently, more synapses. When elevated mTOR signaling was reduced in MHCI-deficient mice, normal synapse density was restored.

Thus, Boulanger said, MHCI and autism-associated genes appear to converge on the mTOR-synapse regulation pathway. This is intriguing given that inflammation during pregnancy, which alters MHCI levels in the fetal brain, may slightly increase the risk of autism in genetically predisposed individuals, she said.

"Up-regulating MHCI is essential for the maternal immune response, but changing MHCI activity in the fetal brain when synaptic connections are being formed could potentially affect synapse density," Boulanger said.

Ben Barres, a professor of neurobiology, developmental biology and neurology at the Stanford University School of Medicine, said that while it is known that both insulin-receptor signaling increases synapse density, and MHCI signaling decreases it, the researchers are the first to show that MHCI actually affects insulin receptors to control synapse density.

"The idea that there could be a direct interaction between these two signaling systems comes as a great surprise," said Barres, who was not involved in the research. "This discovery not only will lead to new insight into how brain circuitry develops but to new insight into declining brain function that occurs with aging."

Particularly, the research suggests a possible functional connection between type II diabetes and Alzheimer's disease, Barres said.

"Type II diabetes has recently emerged as a risk factor for Alzheimer's disease but it has not been clear what the connection is to the synapse loss experienced with Alzheimer's disease," he said. "Given that type II diabetes is accompanied by decreased insulin responsiveness, it may be that the MHCI signaling becomes able to overcome normal insulin signaling and contribute to synapse decline in this disease."

Research during the past 15 years has shown that MHCI lives a prolific double-life in the brain, Boulanger said. The brain is "immune privileged," meaning the immune system doesn't respond as rapidly or effectively to perceived threats in the brain. Dozens of studies have shown, however, that MHCI is not only present throughout the healthy brain, but is essential for normal brain development and function, Boulanger said. A 2013 paper from her lab published in the journal Molecular and Cellular Neuroscience showed that MHCI is even present in the fetal-mouse brain, at a stage when the immune system is not yet mature.

"Many people thought that immune molecules like MHCI must be missing from the brain," Boulanger said. "It turns out that MHCI immune proteins do operate in the brain — they just do something completely different. The dual roles of these proteins in the immune system and nervous system may allow them to mediate both harmful and beneficial interactions between the two systems."

INFORMATION:

The paper, "MHC Class I Limits Hippocampal Synapse Density by Inhibiting Neuronal Insulin Receptor Signaling," was published in the Journal of Neuroscience. Boulanger worked with Carolyn Tyler, a postdoctoral research fellow in PNI; Julianna Poole, who received her master's degree in molecular biology from Princeton in 2014; Princeton senior Joseph Park; and Lawrence Fourgeaud and Tracy Dixon-Salazar, both at UCSD. The work was supported by the Whitehall Foundation; the Sloan Foundation; Cure Autism Now; the Princeton Neuroscience Institute Innovation Fund; the Silvio Varon Chair in Neuroregeneration at UCSD; Autism Speaks; and the National Science Foundation.