(Press-News.org) Customized genome editing – the ability to edit desired DNA sequences to add, delete, activate or suppress specific genes – has major potential for application in medicine, biotechnology, food and agriculture.

Now, in a paper published in Molecular Cell, North Carolina State University researchers and colleagues examine six key molecular elements that help drive this genome editing system, which is known as CRISPR-Cas.

NC State's Dr. Rodolphe Barrangou, an associate professor of food, bioprocessing and nutrition sciences, and Dr. Chase Beisel, an assistant professor of chemical and biomolecular engineering, use CRISPR-Cas to take aim at certain DNA sequences in bacteria and in human cells. CRISPR stands for "clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats," and Cas is a family of genes and corresponding proteins associated with the CRISPR system that specifically target and cut DNA in a sequence-dependent manner.

Essentially, the authors say, bacteria use the system as a defense mechanism and immune system against unwanted invaders such as viruses. Now that same system is being harnessed by researchers to quickly and more precisely target certain genes for editing.

"This paper sheds light on how CRISPR-Cas works," Barrangou said. "If we liken this system to a puzzle, this paper shows what some of the system's pieces are and how they interlock with one another. More importantly, we find which pieces are important structurally or functionally – and which ones are not."

The CRISPR-Cas system is spreading like wildfire among researchers across the globe who are searching for new ways to manipulate genes. Barrangou says that the paper's findings will allow researchers to increase the specificity and efficiency in targeting DNA, setting the stage for more precise genetic modifications.

The work by Barrangou and Beisel holds promise in manipulating relevant bacteria for use in food – think of safer and more effective probiotics for your yogurt, for example – and in model organisms used in agriculture, including gene editing in crops to make them less susceptible to disease.

The collaborative effort with Caribou Biosciences, a start-up biotechnology company in California, illustrates the focus of these two NC State laboratories on bridging the gap between industry and academia, and the commercial potential of CRISPR technologies, the researchers say.

INFORMATION:

"Guide RNA Functional Modules Direct Cas9 Activity and Orthogonality"

Authors: Alexandra E. Briner, Kurt Selle, Chase L. Beisel and Rodolphe Barrangou, North Carolina State University; Paul D. Donohoue, Euan M. Slorach, Christopher H. Nye, Rachel E. Haurwitz, and Andrew P. May, Caribou Biosciences Inc.; Ahmed A. Gomaa, University of Cairo

Published: Oct. 16, 2014, online in Molecular Cell

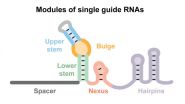

Abstract: The RNA-guided Cas9 endonuclease specifically targets and cleaves DNA in a sequence-dependent manner and has been widely used for programmable genome editing. Cas9 activity is dependent on interactions with guide RNAs, and evolutionarily divergent Cas9 nucleases have been shown to work orthogonally. However, the molecular basis of selective Cas9:guide-RNA interactions is poorly understood. Here, we identify and characterize six conserved modules within native crRNA:tracrRNA duplexes and single guide RNAs (sgRNAs) that direct Cas9 endonuclease activity. We show the bulge and nexus are necessary for DNA cleavage and demonstrate that the nexus and hairpins are instrumental in defining orthogonality between systems. In contrast, the crRNA:tracrRNA complementary region can be modified or partially removed. Collectively, our results establish guide RNA features that drive DNA targeting by Cas9 and open new design and engineering avenues for CRISPR technologies.

A longstanding question among scientists is whether evolution is predictable. A team of researchers from UC Santa Barbara may have found a preliminary answer. The genetic underpinnings of complex traits in cephalopods may in fact be predictable because they evolved in the same way in two distinct species of squid.

Last, year, UCSB professor Todd Oakley and then-Ph.D. student Sabrina Pankey profiled bioluminescent organs in two species of squid and found that while they evolved separately, they did so in a remarkably similar manner. Their findings are published today in ...

Research in recent years has shown that people associate specific facial traits with an individual's personality. For instance, people consistently rate faces that appear more feminine or that naturally appear happy as looking more trustworthy. In addition to trustworthiness, people also consistently associate competence, dominance, and friendliness with specific facial traits. According to an article published by Cell Press on October 21st in Trends in Cognitive Sciences, people rely on these subtle and arbitrary facial traits to make important decisions, from voting for ...

(SALT LAKE CITY)—Workers punching in for the graveyard shift may be better off not eating high-iron foods at night so they don't disrupt the circadian clock in their livers.

Disrupted circadian clocks, researchers believe, are the reason that shift workers experience higher incidences of type 2 diabetes, obesity and cancer. The body's primary circadian clock, which regulates sleep and eating, is in the brain. But other body tissues also have circadian clocks, including the liver, which regulates blood glucose levels.

In a new study in Diabetes online, University ...

DURHAM, N.H. –- Crewed missions to Mars remain an essential goal for NASA, but scientists are only now beginning to understand and characterize the radiation hazards that could make such ventures risky, concludes a new paper by University of New Hampshire scientists.

In a paper published online in the journal Space Weather, associate professor Nathan Schwadron of the UNH Institute for the Study of Earth, Oceans, and Space (EOS) and the department of physics says that due to a highly abnormal and extended lack of solar activity, the solar wind is exhibiting extremely ...

DURHAM, N.H. – Six percent of U.S. children and youth missed a day of school over the course of a year because they were the victim of violence or abuse at school. This was a major finding of a study on school safety by University of New Hampshire researchers published this month in the Journal of School Violence.

"This study really highlights the way school violence can interfere with learning," says lead author David Finkelhor, professor of sociology and director of the Crimes Against Children Research Center (CCRC) at UNH. "Too many kids are missing school ...

New research shows that a preservation technique known as sequential subnormothermic ex vivo liver perfusion (SNEVLP) prevents ischemic type biliary stricture following liver transplantation using grafts from donations after cardiac death (DCD). Findings published in Liver Transplantation, a journal of the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases and the International Liver Transplantation Society, indicate that the preservation of DCD grafts using SNEVLP versus cold storage reduces bile duct and endothelial cell injury post transplantation.

The shortage ...

VIDEO:

Scientists at the US Department of Energy's Ames Laboratory modeled the 'passing probability' of molecules within the narrow pores of mesoporous nanoparticles. This understanding will help determine the optimal diameter...

Click here for more information.

Scientists at the U.S. Department of Energy's Ames Laboratory have developed deeper understanding of the ideal design for mesoporous nanoparticles used in catalytic reactions, such as hydrocarbon conversion to biofuels. ...

ATLANTA—Animal-assisted therapy can reduce symptoms of anxiety and loneliness among college students, according to researchers at Georgia State University, Idaho State University and Savannah College of Art and Design. Their findings are published in the latest issue of the Journal of Creativity in Mental Health.

The researchers provided animal-assisted therapy to 55 students in a group setting at a small arts college in the Southeast. They found a 60 percent decrease in self-reported anxiety and loneliness symptoms following animal-assisted therapy, in which a ...

MADISON, Wis. — Developing invisible implantable medical sensor arrays, a team of University of Wisconsin-Madison engineers has overcome a major technological hurdle in researchers' efforts to understand the brain.

The team described its technology, which has applications in fields ranging from neuroscience to cardiac care and even contact lenses, in the Oct. 20 issue of the online journal Nature Communications.

Neural researchers study, monitor or stimulate the brain using imaging techniques in conjunction with implantable sensors that allow them to continuously ...

WASHINGTON D.C. Oct. 21, 2014 -- The most obvious effects of too much sun exposure are cosmetic, like wrinkled and rough skin. Some damage, however, goes deeper—ultraviolet light can damage DNA and cause proteins in the body to break down into smaller, sometimes harmful pieces that may also damage DNA, increasing the risk of skin cancer and cataracts. Understanding the specific pathways by which this degradation occurs is an important step in developing protective mechanisms against it.

Researchers from the École Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne ...