(Press-News.org) Our immune system defends us from harmful bacteria and viruses, but, if left unchecked, the cells that destroy those invaders can turn on the body itself, causing auto-immune diseases like type-1 diabetes or multiple sclerosis. A molecule called insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1) boosts the body's natural defence against this 'friendly fire', scientists at the European Molecular Biology Laboratory (EMBL) in Monterotondo, Italy, have found. The findings, published today in EMBO Molecular Medicine, are especially exciting because IGF-1 is already approved for use in patients, which could speed up the move to clinical trials for treating auto-immune diseases.

"To me what was really striking was the survival rate for multiple sclerosis," says Daniel Bilbao, who conducted the research with Nadia Rosenthal's lab at EMBL, "we went from less than 50% survival in untreated animals to over 80% survival in animals that received IGF-1."

In patients with auto-immune diseases, a group of cells called pro-inflammatory T-effector cells become sensitized to specific cells in the body, identifying them as foreign and attacking them as if they were invading bacteria. If this misdirected attack targets the insulin-producing cells in the pancreas, the result is diabetes; if it affects myelin-sheathed cells in the central nervous system, the person suffers from multiple sclerosis. These attacks on the body's own cells go unchecked due to the failing of another type of immune cell: T-regulatory (T-reg) cells, which, as their name implies, control T-effector cells, shutting them down when they are not needed.

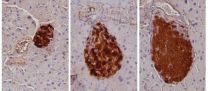

Working with then PhD student Luisa Luciani, Bilbao and Rosenthal found that, if mice with conditions that mimic type-1 diabetes and multiple sclerosis received IGF-1, they started producing more T-reg cells where they were needed – the pancreas and the central nervous system, respectively – and the disease was suppressed. The scientists went on to test IGF-1's effects on T-reg cells taken from both mice and humans, confirming that IGF-1 acts directly on T-reg cells – rather than indirectly by affecting some other factor that induces T-reg cells to multiply.

In a separate study published earlier this year, Bilbao and Rosenthal had found that IGF-1 has the same effect on another condition in which the immune system goes awry. They found that allergic contact dermatitis, an inflammatory skin disease thought to affect as many as one in five Europeans, is also suppressed in mice by treating them with IGF-1.

"These studies have real clinical significance, because IGF-1 is already an approved therapeutic, which has been tested in many different settings, so it will be much easier to start clinical trials for IGF-1 in auto-immune and inflammatory diseases than it would if we were proposing a new, untested drug,' says Nadia Rosenthal, former Head of EMBL Monterotondo, and currently at Imperial College London, UK, and Monash University, Australia, where she is Scientific Head of EMBL Australia.

"My hope and goal is to now see this applied to humans, but – as with everything – that will depend on funding," Bilbao adds.

Rosenthal is planning to further explore the role of IGF-1 in inflammation and regeneration, and its potential for treating conditions such as muscular atrophy, fibrosis or heart disease.

INFORMATION:

Daniel Bilbao, who conducted the research, is available for interviews in Spanish and Italian.

Using two world-class supercomputers, the researchers were able to demonstrate the effectiveness of their approach by simulating the formation of a massive galaxy at the dawn of cosmic time. The ALMA radio telescope – which stands at an elevation of 5,000 meters in the Atacama Desert of Chile, one of the driest places on earth – was then used to forge observations of the galaxy, showing how their method improves upon previous efforts.

It is extremely difficult to gather information about galaxies at the edge of the Universe: the signals from these heavenly ...

CHICAGO (October 22, 2014) – New research shows vulnerable patients in the Intensive Care Unit (ICU) who received enhanced oral care from a dentist were at significantly less risk for developing a lower respiratory tract infection (LRTI), like ventilator-associated pneumonia, during their stay. The study was published in the November issue of Infection Control and Hospital Epidemiology, the journal of the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America (SHEA).

"Bacteria causing healthcare-associated infections often start in the oral cavity," said Fernando Bellissimo-Rodrigues, ...

CHICAGO (October 22, 2014) – New research found tracking influenza vaccination of healthcare personnel through an automated system increased vaccination compliance and reduced workload burden on human resources and occupational health staff. The study is published in the November issue of Infection Control and Hospital Epidemiology, the journal of the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America (SHEA).

"Mandatory vaccination programs help protect vulnerable patients, but can be tremendously time and resource dependent," said Susan Huang, MD, MPH, an author of ...

Frying is one of the world's most popular ways to prepare food — think fried chicken and french fries. Even candy bars and whole turkeys have joined the list. But before dunking your favorite food in a vat of just any old oil, consider using olive. Scientists report in ACS' Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry that olive oil withstands the heat of the fryer or pan better than several seed oils to yield more healthful food.

Mohamed Bouaziz and colleagues note that different oils have a range of physical, chemical and nutritional properties that can degrade ...

Drawing blood and testing it is standard practice for many medical diagnostics. As a less painful alternative, scientists are developing skin patches that could one day replace the syringe. In the ACS journal Analytical Chemistry, one team reports they have designed and successfully tested, for the first time, a small skin patch that detected malaria proteins in live mice. It could someday be adapted for use in humans to diagnose other diseases, too.

Simon R. Corrie and colleagues note that while blood is rich with molecular clues that tell a story about a person's health, ...

Action-packed science-fiction movies often feature colourful laser bolts. But what would a real laser missile look like during flight, if we could only make it out? How would it illuminate its surroundings? The answers lie in a film made at the Laser Centre of the Institute of Physical Chemistry of the Polish Academy of Sciences in cooperation with the Faculty of Physics at the University of Warsaw.

Tests of a new compact high-power laser have given researchers at the Laser Centre of the Institute of Physical Chemistry of the Polish Academy of Sciences and the Faculty ...

"We're using less expensive raw materials in smaller amounts, we have fewer production steps, and have potentially lower total energy consumption," PhD candidate Fredrik Martinsen and Professor Ursula Gibson of the Department of Physics at NTNU explain.

They recently published their technique in Scientific Reports.

Their processing technique allows them to make solar cells from silicon that is 1000 times less pure, and thus less expensive, than the current industry standard.

Glass fibers with a silicon core

The researchers' solar cells are composed of silicon fibers ...

Bright colours appear on a fruit fly's transparent wings against a dark background as a result of light refraction. Researchers from Lund University in Sweden have now demonstrated that females choose a mate based on the males' hidden wing colours.

"Our experiment shows that this newly-discovered trait is important in female choice in fruit flies, and is the first evidence that wing interference patterns have a biological signalling function between the sexes during sexual selection", said Jessica Abbott, a biologist at Lund University.

The extremely thin wings of the ...

DURHAM, N.C. -- Doctors at Duke University Hospital have developed a new collaborative model in cancer care that reduced the rates at which patients were sent to intensive care or readmitted to the hospital after discharge.

The Duke researchers shared their findings today at the Palliative Care in Oncology Symposium sponsored by the American Society of Clinical Oncology.

In the new treatment model, medical oncologists and palliative care physicians partnered in a "co-rounding" format to deliver cancer care for patients admitted to Duke University Hospital's solid tumor ...

Predicting which people will commit murder is extremely difficult, according to a new study by criminologists at The University of Texas at Dallas.

Dr. Alex Piquero, Ashbel Smith Professor of criminology and co-author of the paper, said he and his fellow researchers were motivated by the lack of scientific literature on distinguishing people who will commit homicide from those who will not.

According to the study, the similarities outweigh the differences between the two groups.

"Based on a whole slew of characteristics that we know predict and differentiate criminal ...