(Press-News.org) Adherent cells, the kind that form the architecture of all multi-cellular organisms, are mechanically engineered with precise forces that allow them to move around and stick to things. Proteins called integrin receptors act like little hands and feet to pull these cells across a surface or to anchor them in place. When groups of these cells are put into a petri dish with a variety of substrates they can sense the differences in the surfaces and they will "crawl" toward the stiffest one they can find.

Now chemists have devised a method using DNA-based tension probes to zoom in at the molecular level and measure and map these phenomena: How cells mechanically sense their environments, migrate and adhere to things.

Nature Communications published the research, led by the lab of Khalid Salaita, assistant professor of biomolecular chemistry at Emory University. Co-authors include mechanical and biological engineers from Georgia Tech.

Using their new method, the researchers showed how the forces applied by fibroblast cells is actually distributed at the individual molecule level. "We found that each of the integrin receptors on the perimeter of cells is basically 'feeling' the mechanics of its environment," Salaita says. "If the surface they feel is softer, they will unbind from it and if it's more rigid, they will bind. They like to plant their stakes in firm ground."

Each cell has thousands of these integrin receptors that span the cellular membrane. Cell biologists have long been focused on the chemical aspects of how integrin receptors sense the environment and interact with it, while the understanding of the mechanical aspects lagged. Cellular mechanics is a relatively new but growing field, which also involves biophysicists, engineers, chemists and other specialists.

"Lots of good and bad things that happen in the body are mediated by these integrin receptors, everything from wound healing to metastatic cancer, so it's important to get a more complete picture of how these mechanisms work," Salaita says.

The Salaita lab previously developed a fluorescent-sensor technique to visualize and measure mechanical forces on the surface of a cell using flexible polymers that act like tiny springs. These springs are chemically modified at both ends. One end gets a fluorescence-based turn-on sensor that will bind to an integrin receptor on the cell surface. The other end is chemically anchored to a microscope slide and a molecule that quenches fluorescence. As force is applied to the polymer spring, it extends. The distance from the quencher increases and the fluorescent signal turns on and grows brighter. Measuring the amount of fluorescent light emitted determines the amount of force being exerted.

Yun Zhang, a co-author of the Nature Communications paper and a graduate student in the Salaita lab, had the idea of using DNA molecular beacons instead of flexible polymers. "She was new to the lab and brought a fresh perspective," Salaita says.

The molecular beacons are short pieces of lab-synthesized DNA, each consisting of about 20 base pairs, used in clinical diagnostics and research. The beacons are called DNA hairpins because of their shape.

The thermodynamics of DNA, its double-strand helix structure and the energy needed for it to fold are well understood, making the DNA hairpins more refined instruments for measuring force. Another key advantage is the fact that their ends are consistently the same distance apart, Salaita says, unlike the random coils of flexible polymers.

In experiments, the DNA hairpins turned out to operate more like a toggle switch than a dimmer switch. "The polymer-based tension probes gradually unwind and become brighter as more force is applied," Salaita says. "In contrast, DNA hairpins don't budge until you apply a certain amount of force. And once that force is applied, they start unzipping and just keep unraveling."

In addition, the researchers were able to calibrate the force constant of the DNA hairpins, making them highly tunable, digital instruments for calculating the amount of force applied by a molecule, down to the piconewton level.

"The force of gravity on an apple is about one newton, so we're talking about a million-millionth of that," Salaita says. "It's sort of mind-bogging that that's how little force you need to unfold a piece of DNA."

The result is a tension probe that is three times more sensitive than the polymer probes.

In a separate paper, published in Nano Letters, the Salaita lab used the DNA-based probes to experiment with how the density of a substrate affects the force applied. "Intuitively you might think that a less dense environment, offering fewer anchoring points, would result in more force per anchor," Salaita said. "We found that it's actually the opposite: You're going to see less force per anchor."

The mechanism of sensing ligand spacing and adhering to a substrate appears to be force-mediated, he says. "The integrin receptors need to be closely spaced in order for the engine in the cell that generates force to engage with them and commit the force."

Now the researchers are using the DNA-based tools they've developed to study the forces of more sensitive cellular pathways and receptors.

"Integrin receptors are kind of beasts, they apply relatively high forces in order to adhere to the extracellular matrix," Salaita says. "There are lots of different cell receptors that apply much weaker forces."

T cells, for example, are white blood cells whose receptors are focused not on adhesion but on activities like distinguishing a friendly self-peptide from a foreign bacterial peptide.

The Salaita lab is collaborating with medical researchers across Emory to understand the role of cellular mechanics in the immune system, blood clotting and neural patterning of axons.

"Basically, our premise is that mechanics play a role in almost all biological processes, and with these DNA-based tension probes we're going to uncover, measure and map those forces," Salaita says.

INFORMATION:

Tempe, Ariz. (Oct. 23, 2014) - New research findings from a team of prevention scientists at Arizona State University demonstrates that a family-focused intervention program for middle-school Mexican American children leads to fewer drop-out rates and lower rates of alcohol and illegal drug use.

"This is the first randomized prevention trial that we're aware of to show effects on school dropout for this population," said Nancy Gonzales, Foundation Professor in the REACH Institute and Psychology Department, College of Liberal Arts and Sciences at Arizona State University. ...

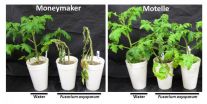

RIVERSIDE, Calif. – Plant breeders have long identified and cultivated disease-resistant varieties. A research team at the University of California, Riverside has now revealed a new molecular mechanism for resistance and susceptibility to a common fungus that causes wilt in susceptible tomato plants.

Study results appeared Oct. 16 in PLOS Pathogens.

Katherine Borkovich, a professor of plant pathology and the chair of the Department of Plant Pathology and Microbiology, and colleagues started with two closely related tomato cultivars: "Moneymaker" is susceptible ...

ORLANDO, Fla. – New research shows obese children with asthma may mistake symptoms of breathlessness for loss of asthma control leading to high and unnecessary use of rescue medications. The study was published online in the Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology (JACI), the official scientific journal of the American Association of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology.

"Obese children with asthma need to develop a greater understanding of the distinct feeling of breathlessness in order to avoid not just unnecessary medication use, but also the anxiety, reduced quality ...

Just three years ago, a patient at Sahlgrenska University Hospital received a blood vessel transplant grown from her own stem cells.

Suchitra Sumitran-Holgersson, Professor of Transplantation Biology at The Univerisity of Gothenburg, and Michael Olausson, Surgeon/Medical Director of the Transplant Center and Professor at Sahlgrenska Academy, came up with the idea, planned and carried out the procedure.

Missing a vein

Professors Sumitran-Holgersson and Olausson have published a new study in EBioMedicine based on two other transplants that were performed in 2012 at Sahlgrenska ...

Gossip is pervasive in our society, and our penchant for gossip can be found in most of our everyday conversations. Why are individuals interested in hearing gossip about others' achievements and failures? Researchers at the University of Groningen in the Netherlands studied the effect positive and negative gossip has on how the recipient evaluates him or herself. The study is published in Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin.

In spite of some positive consequences, gossip is typically seen as destructive and negative. However, hearing gossip may help individuals ...

New data shows that healthcare and personal costs to support survivors of stroke remains high 10 years on.

The Monash University research, published today in the journal Stroke, is the first to look at the long-term costs for the two main causes of stroke; ischemic where the blood supply stops due to a blood clot, and hemorrhagic, which occurs when a weakened blood vessel supplying the brain bursts.

Previous studies based on estimating the lifetime costs using patient data up to 5 years after a stroke, suggested that costs peaked in the first year and then declined ...

Metamaterials, a hot area of research today, are artificial materials engineered with resonant elements to display properties that are not found in natural materials. By organizing materials in a specific way, scientists can build materials with a negative refractivity, for example, which refract light at a reverse angle from normal materials. However, metamaterials up to now have harbored a significant downside. Unlike natural materials, they are two-dimensional and inherently anisotropic, meaning that they are designed to act in a certain direction. By contrast, three-dimensional ...

An unprecedented boom in hydropower dam construction is underway, primarily in developing countries and emerging economies. While this is expected to double the global electricity production from hydropower, it could reduce the number of our last remaining large free-flowing rivers by about 20% and pose a serious threat to freshwater biodiversity. A new database has been developed to support decision making on sustainable modes of electricity production. It is presented today at the international congress Global Challenges: Achieving Sustainability hosted by the University ...

October 24, 2014 – For patients with a severe type of stroke called subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH), treatment at a hospital that treats a high volume of SAH cases is associated with a lower risk of death, reports a study in the November issue of Neurosurgery, official journal of the Congress of Neurological Surgeons. The journal is published by Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, a part of Wolters Kluwer Health.

After adjustment for other factors, the mortality rate after SAH is about one-fifth lower at high-volume hospitals, according to the report by Dr. Shyam Prabhakaran ...

The Roman-British population from c. 200-400 AD appears to have had far less gum disease than we have today, according to a study of skulls at the Natural History Museum led by a King's College London periodontist. The surprise findings provide further evidence that modern habits like smoking can be damaging to oral health.

Gum disease, also known as periodontitis, is the result of a chronic inflammatory response to the build-up of dental plaque. Whilst much of the population lives with mild gum disease, factors such as tobacco smoking or medical conditions like diabetes ...