(Press-News.org) The heart holds its own pool of immune cells capable of helping it heal after injury, according to new research in mice at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis.

Most of the time when the heart is injured, these beneficial immune cells are supplanted by immune cells from the bone marrow, which are spurred to converge in the heart and cause inflammation that leads to further damage. In both cases, these immune cells are called macrophages, whether they reside in the heart or arrive from the bone marrow. Although they share a name, where they originate appears to determine whether they are helpful are harmful to an injured heart.

In a mouse model of heart failure, the researchers showed that blocking the bone marrow's macrophages from entering the heart protects the organ's beneficial pool of macrophages, allowing them to remain in the heart, where they promote regeneration and recovery. The findings may have implications for treating heart failure in humans.

The study is now available in The Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences Early Edition.

"Researchers have known for a long time that the neonatal mouse heart can recover well from injury, and in some cases can even regenerate," said first author Kory J. Lavine, MD, PhD, instructor in medicine. "If you cut off the lower tip of the neonatal mouse heart, it can grow back. But if you do the same thing to an adult mouse heart, it forms scar tissue."

This disparity in healing capacity was long a mystery because the same immune cells appeared responsible for both repair and damage. Until recently, it was impossible to distinguish the helpful macrophages that reside in the heart from the harmful ones that arrive from the bone marrow.

The new research and past work by the same group — led by Douglas L. Mann, MD, the Tobias and Hortense Lewin Professor of Medicine and cardiologist-in-chief at Barnes-Jewish Hospital — appear to implicate these immune cells of different origins as responsible for the difference in healing capacity seen in neonatal and adult hearts, at least in mice.

"The same macrophages that promote healing after injury in the neonatal heart also are present in the adult heart, but they seem to go away with injury," Lavine said. "This may explain why the young heart can recover while the adult heart can't."

Because they are interested in human heart failure, Lavine and his colleagues developed a method to progressively damage mouse cardiac tissue in a way that mimicked heart failure. They compared the immune response to cardiac damage in neonatal and adult mouse hearts.

The investigators found that the helpful macrophages originate in the embryonic heart and harmful macrophages originate in the bone marrow and could be distinguished by whether they express a protein on their surface called CCR2. Macrophages without CCR2 originate in the heart; those with CCR2 come from the bone marrow, the research showed.

Lavine and his colleagues asked whether a compound that inhibits the CCR2 protein would block the bone marrow's macrophages from entering the heart.

"When we did that, we found that the macrophages from the bone marrow did not come in," Lavine said. "And the macrophages native to the heart remained. We saw reduced inflammation in these injured adult hearts, less oxidative damage and improved repair. We also saw new blood vessel growth. By blocking the CCR2 signaling, we were able to keep the resident macrophages around and promote repair."

Some CCR2 inhibitors are being tested in phase 1 and 2 clinical trials for treating rheumatoid arthritis. But before these drugs can be evaluated in people with heart failure, more work must be done to find out whether the same mechanisms are at work in human hearts, according to the researchers.

"We have identified similar immune cell subtypes that are present in the human heart," Lavine said. "We need to find out more about their roles in heart failure in patients and understand more about how macrophages that reside in the heart promote repair."

INFORMATION:

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIH), the Oliver Langenberg Physician-Scientist Training Program and the Washington University Center for the Investigation of Membrane Excitability Diseases Live Cell Imaging Facility. (Grant numbers T32 HL007081, K08 HL123519, R01 HL111094, R01 HL105732.)

Lavine KJ, Epelman S, Uchida K, Weber KJ, Nichols CG, Schilling JD, Ornitz DM, Randolph GJ, Mann DL. Distinct macrophage lineages contribute to disparate patterns of cardiac recovery and remodeling in the neonatal and adult heart. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, PNAS Early Edition. Oct. 27, 2014.

Washington University School of Medicine's 2,100 employed and volunteer faculty physicians also are the medical staff of Barnes-Jewish and St. Louis Children's hospitals. The School of Medicine is one of the leading medical research, teaching and patient-care institutions in the nation, currently ranked sixth in the nation by U.S. News & World Report. Through its affiliations with Barnes-Jewish and St. Louis Children's hospitals, the School of Medicine is linked to BJC HealthCare.

BOSTON — Findings published in the Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation show that imperceptible vibratory stimulation applied to the soles of the feet improved balance by reducing postural sway and gait variability in elderly study participants. The vibratory stimulation is delivered by a urethane foam insole with embedded piezoelectric actuators, which generates the mechanical stimulation. The study was conducted by researchers from the Institute for Aging Research (IFAR) at Hebrew SeniorLife, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, the Wyss Institute for ...

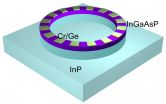

A significant breakthrough in laser technology has been reported by the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE)'s Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (Berkeley Lab) and the University of California (UC) Berkeley. Scientists led by Xiang Zhang, a physicist with joint appointments at Berkeley Lab and UC Berkeley, have developed a unique microring laser cavity that can produce single-mode lasing even from a conventional multi-mode laser cavity. This ability to provide single-mode lasing on demand holds ramifications for a wide range of applications including optical metrology and ...

Lab-grown tissues could one day provide new treatments for injuries and damage to the joints, including articular cartilage, tendons and ligaments.

Cartilage, for example, is a hard material that caps the ends of bones and allows joints to work smoothly. UC Davis biomedical engineers, exploring ways to toughen up engineered cartilage and keep natural tissues strong outside the body, report new developments this week in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

"The problem with engineered tissue is that the mechanical properties are far from those ...

Washington, DC—The Endocrine Society today issued a Clinical Practice Guideline (CPG) for the diagnosis and treatment of acromegaly, a rare condition caused by excess growth hormone in the blood.

The CPG, entitled "Acromegaly: An Endocrine Society Clinical Practice Guideline," appeared in the November 2014 issue of the Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism (JCEM), a publication of the Endocrine Society.

Acromegaly is usually caused by a non-cancerous tumor in the pituitary gland. The tumor manufactures too much growth hormone and spurs the body to overproduce ...

Chicago, October 30, 2014—Analysis of data from an institutional patient registry on stereotactic body radiotherapy (SBRT) indicates excellent long-term, local control, 79 percent of tumors, for medically inoperable, early stage lung cancer patients treated with SBRT from 2003 to 2012, according to research presented today at the 2014 Chicago Multidisciplinary Symposium in Thoracic Oncology. The Symposium is sponsored by the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO), the American Society for Radiation Oncology (ASTRO), the International Association for the Study ...

BUFFALO, N.Y. – You have to be at least 2 years old to be covered by U.S. dietary guidelines. For younger babies, no official U.S. guidance exists other than the general recommendation by national and international organizations that mothers exclusively breastfeed for at least the first six months.

So what do American babies eat?

That's the question that motivated researchers at the University at Buffalo School of Medicine and Biomedical Sciences to study the eating patterns of American infants at 6 months and 12 months old, critical ages for the development of ...

NOAA's GOES-West satellite captured an image of the birth of the Eastern Pacific Ocean's twenty-first tropical depression, located far south of Acapulco, Mexico.

NOAA's GOES-West satellite gathered infrared data on newborn Tropical Depression 21E (TD 21E) and that data was made into an image by NASA/NOAA's GOES Project at NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland. At 1200 UTC (9 a.m. EDT), the GOES-West image showed that thunderstorms circled the low-level center and extended northeast of the center indicating that southwesterly wind shear was affecting ...

Professor Elly Tanaka and her research group at the DFG Research Center for Regenerative Therapies Dresden - Cluster of Excellence at the TU Dresden (CRTD) demonstrated for the first time the in vitro growth of a piece of spinal cord in three dimensions from mouse embryonic stem cells. Correct spatial organization of motor neurons, interneurons and dorsal interneurons along the dorsal/ventral axis was observed.

This study has been published online by the American journal "Stem Cell Reports" on 30.10.2014.

For many years Elly Tanaka and her research group have been studying ...

As transistors get smaller, they also grow less reliable. Increasing their operating voltage can help, but that means a corresponding increase in power consumption.

With information technology consuming a steadily growing fraction of the world's energy supplies, some researchers and hardware manufacturers are exploring the possibility of simply letting chips botch the occasional computation. In many popular applications — video rendering, for instance — users probably wouldn't notice the difference, and it could significantly improve energy efficiency.

At ...

Global warming is altering the reproduction of plants and animals, notably accelerating the date when reproduction and other life processes occur. A study by the University of Uppsala (Sweden), including the participation of Spanish researcher Germán Orizaola, has discovered that some amphibians are capable of making their offspring grow at a faster rate if they have been born later due to the climate.

Over recent decades many organisms, both plants and animals, have experienced a notable advance in the date when many of their life processes (like reproduction, migration ...