(Press-News.org) The current Ebola outbreak shows how quickly diseases can spread with global jet travel.

Yet, knowing how to predict the spread of these epidemics is still uncertain, because the complicated models used are not fully understood, says a University of California, Berkeley biophysicist.

Using a very simple model of disease spread, Oskar Hallatschek, assistant professor of physics, proved that one common assumption is actually wrong. Most models have taken for granted that if disease vectors, such as humans, have any chance of "jumping" outside the initial outbreak area – by plane or train, for example – the outbreak quickly metastasizes into an epidemic.

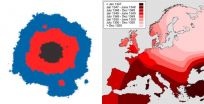

Hallatschek and coauthor Daniel S. Fisher of Stanford University found instead that if the chance of long-distance dispersal is low enough, the disease spreads quite slowly, like a wave rippling out from the initial outbreak. This type of spread was common centuries ago when humans rarely traveled. The Black Death spread through 14th century Europe as a wave, for example.

But if the chance of jumping is above a threshold level – which is often the situation today with frequent air travel –the diseases can generate enough satellite outbreaks to spread like wildfire. And the greater the chance that people can hop around the globe, the faster the spread.

"With our simple model, we clearly show that one of the key factors that controls the spread of infection is how common long-range jumps are in the dispersal of a disease," said Hallatschek, who is the William H. McAdams Chair in physics and a member of the UC Berkeley arm of the California Institute for Quantitative Biosciences (QB3). "And what matters most are the rare cases of extremely long jumps, the individuals who take plane trips to distant places and potentially spread the disease."

This new understanding of a simple computer model of disease spread will help epidemiologists understand the more complex models now used to predict the spread of epidemics, he said, but also help scientists understand the spread of cancer metastases, genetic mutations in animal or human populations, invasive species, wildfires and even rumors.

The paper appears in this week's Online Early Edition of the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Epidemic spread

Hallatschek typically studies in a Petri dish how new mutations spread in colonies of microbes, activity that he models mathematically to understand how evolution fixes new traits in a population. When looking at simple theories of such "epidemic" spread, however, he was surprised to discover that no one knew the answer to a simple question: How does the long-distance dispersal of individuals during an outbreak affect the spread?

Simulations show that if the chance of individuals traveling away from the center of an outbreak drops off exponentially with distance – for example, if the chance of distant travel drops by half every 10 miles – the disease spreads as a relatively slow wave.

Simulations also suggested that a slower "power-law" drop off – for example, if the chance of distant travel drops by half every time the distance is doubled – would let the disease get quickly out of control.

"We were shocked to see that this had not been demonstrated, and saw a chance to prove something really fundamental," Hallatschek said.

The simple model he used was stripped of real-world complexity, but contained the crucial ingredients needed to predict evolutionary spread and, more importantly, could be captured by a mathematical formula. Hallatschek discovered three types of epidemic situations involving power-law distributions.

In cases where long-range jumps are very rare, epidemics spread in a slow wave, typified by the Black Death. The invasive cane toad also spread in a slow wave after being introduced to Australia in the 1930s. When long-range jumps are common, the disease spreads very rapidly, as in 2002-2003 with SARS (severe acute respiratory syndrome), which was spread around the world by air travelers. An intermediate situation produces satellite outbreaks, but spreads far more slowly than SARS-like cases.

Hallatschek said that previous studies failed to take into account the randomness of jumps, which led people to think that any long-range jump would lead to new outbreaks and rapid spread. But if long-range jumps are extremely rare, distant outbreaks tend to be overtaken by the slow, wavelike spread of the initial outbreak before they can contribute much to the overall epidemic.

He noted that two recent studies of human dispersal – the "Where's George?" dollar bill tracking study and a 2008 cell phone user mobility study – suggest that in the real world, humans disperse according to a power-law distribution over distances of up to hundreds of kilometers and exponentially over even longer distances.

In the future, he plans to make his model more and more realistic, first by incorporating networks to mimic the real world where people do not jump randomly, but must travel through airport hubs or train stations. Hallatschek also hopes to test his model by using data on the evolving genome sequences of pathogens as they spread, which provide one measure of where and when satellite outbreaks occur.

INFORMATION:

The work was supported by the Simons Foundation and QB3, as well as grants from Germany's Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft and the U.S. National Science Foundation.

Researchers using a new type of tracking device on female elephant seals have discovered that adding body fat helps the seals dive more efficiently by changing their buoyancy.

The study, published November 5 in the Proceedings of the Royal Society B, looked at the swimming efficiency of elephant seals during their feeding dives and how that changed in the course of months-long migrations at sea as the seals put on more fat. The results showed that when elephant seals are neutrally buoyant--meaning they don't float up or sink down in the water--they spend less energy ...

A University of Oregon researcher wants those "R" words to resonate among young athletes. They are key terms used in an online educational tool designed to teach coaches, educators, teens and parents about concussions.

Brain 101: The Concussion Playbook successfully increased knowledge and attitudes related to brain injuries among students and parents in a study that compared its use in 12 high schools with the usual care practices of 13 other high schools during the fall 2011 sports season. The findings are online ahead of print in the Journal of Adolescent Health.

Participants, ...

A study led by a researcher from Plymouth University in the UK, has discovered that the inhibition of a particular mitochondrial fission protein could hold the key to potential treatment for Parkinson's Disease (PD).

The findings of the research are published today, 5th November 2014, in Nature Communications.

PD is a progressive neurological condition that affects movement. At present there is no cure and little understanding of why some people get the condition. In the UK one on 500 people, around 127,000, have PD.

The debilitating movement symptoms of the disease ...

ANN ARBOR, Mich. — Millions of people with diabetes take medicine to ease the shooting, burning nerve pain that their disease can cause. And new research suggests that no matter which medicine their doctor prescribes, they'll get relief.

But some of those medicines cost nearly 10 times as much as others, apparently with no major differences in how well they ease pain, say a pair of University of Michigan Medical School experts in a new commentary in the Annals of Internal Medicine.

That makes cost -- not effect -- a crucial factor in deciding which medicine ...

TALLAHASSEE, Fla. — A new study by a Florida State University researcher reveals that a new dietary supplement is superior to calcium and vitamin D when it comes to bone health.

Over 12 months, Bahram H. Arjmandi, Margaret A. Sitton Professor in the Department of Nutrition, Food and Exercise Sciences and Director of the Center for Advancing Exercise and Nutrition Research on Aging (CAENRA) at Florida State, studied the impact of the dietary supplement KoACT® versus calcium and vitamin D on bone loss. KoACT is a calcium-collagen chelate, a compound containing ...

A child's ability to distinguish musical rhythm is related to his or her capacity for understanding grammar, according to a recent study from a researcher at the Vanderbilt Kennedy Center.

Reyna Gordon, Ph.D., a research fellow in the Department of Otolaryngology and at the Vanderbilt Kennedy Center, is the lead author of the study that was published online recently in the journal Developmental Science. She notes that the study is the first of its kind to show an association between musical rhythm and grammar.

Though Gordon emphasizes that more research will be necessary ...

VTT Technical Research Centre of Finland has developed an innovative magnetometer that can replace conventional technology in applications such as neuroimaging, mineral exploration and molecular diagnostics. Its manufacturing costs are between 70 and 80 per cent lower than those of traditional technology, and the device is not as sensitive to external magnetic fields as its predecessors. The design of the magnetometer also makes it easier to integrate into measuring systems.

Magnetometers are sensors that measure magnetic fields or changes in magnetic fields. The kinetic ...

Although gluten-free foods are trendy among the health-conscious, they are necessary for those with celiac disease. But gluten, the primary trigger for health problems in these patients, may not be the only culprit. Scientists are reporting in ACS' Journal of Proteome Research that people with the disease also have reactions to non-gluten wheat proteins. The results could help scientists better understand how the disease works and could have implications for how to treat it.

Armin Alaedini, Susan B. Altenbach and colleagues point out that celiac disease symptoms are triggered ...

Photosynthesis is one of the most important processes in nature. The complex method by which all green plants harvest sunlight and thereby produce the oxygen in our air is still not fully understood. Researchers have used DESY's X-ray light source PETRA III to investigate a photosynthesis subsystem in a near-natural state. According to the scientists led by Privatdozentin Dr. Athina Zouni from the Humboldt University (HU) Berlin, X-ray diffraction experiments on the so-called photosystem II revealed structures which were yet unknown. The results are published in the scientific ...

Many pollutants with the potential to meddle with hormones — with bisphenol A (BPA) as a prime example — are already common in the environment. In an effort to clean up these pollutants found in the soil and waterways, scientists are now reporting a novel way to break them down by recruiting help from nanoparticles and light. The study appears in the journal ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces.

Nikhil R. Jana and Susanta Kumar Bhunia explain that the class of pollutants known as endocrine disruptors has been shown to either mimic or block hormones in animals, ...