MU researchers offer first analysis of new human glucose disorder

Findings are informing human research into rare, sometimes fatal glycogen storage disease

2014-11-11

(Press-News.org) COLUMBIA, Mo. - Glycogen storage disorders, which affect the body's ability to process sugar and store energy, are rare metabolic conditions that frequently manifest in the first years of life. Often accompanied by liver and muscle disease, this inability to process and store glucose can have many different causes, and can be difficult to diagnose. Now, researchers at the University of Missouri who have studied enzymes involved in metabolism of bacteria and other organisms have catalogued the effects of abnormal enzymes responsible for one type of this disorder in humans. Their work could help with patient prognosis and in developing therapeutic options for this glycogen storage disease.

"In February of this year, I found an article in the New England Journal of Medicine (NEJM) that caught my eye," said Lesa Beamer, associate professor of chemistry and biochemistry at MU. "It was a landmark study identifying a new, inherited metabolic disorder in humans called phosphoglucomutase 1 (PGM1) deficiency, and affects the human versions of the very same enzymes I had studied."

The NEJM study was the first to characterize the multiple effects of the disorder in humans and pinpointed the enzyme involved. The disorder, described initially in 21 patients, is considered rare but will likely be found more often now that genetic tests have been developed. According to the study, the disease often affects patients in early childhood or adolescence, and can cause hypoglycemia, muscle disease, hormonal abnormalities, and cardiac problems. Many patients exhibit exercise intolerance and, because the condition could not previously be diagnosed, these problems sometimes led to early deaths.

Beamer's lab researches similar enzymes in bacteria that play important roles in carbohydrate (sugar) metabolism, including sugars like glucose. These enzymes perform the same chemical reaction as the human protein involved in the newly identified inherited disease, and share many other similarities.

"Once the disease involving the human equivalent had been identified, we were able to put the knowledge we've gained to immediate use," Beamer said. "Using the information provided by the NEJM study, we recreated the mutated proteins that cause the disorder in a test tube, and conducted detailed biochemical analyses. Our study was the first to systematically characterize and index these mutant proteins for comparison with the symptoms in human patients. Because patient studies are complex and time-consuming, our biochemical analyses are proving essential to understanding the complicated clinical presentation of this inherited disorder."

The early-stage results of this research are promising. If additional studies are successful, Beamer believes that her bacterial enzyme research could assist with further research studying the development of human genetic health tests and therapeutics within the next few years. Her lab currently is collaborating with human medical researchers to "fast track" the study of this rare disease.

INFORMATION:

Beamer holds joint appointments in the Department of Chemistry in the College of Arts and Science and the Department of Biochemistry in the School of Medicine and the College of Agriculture, Food and Natural Resources at MU.

The study, "Compromised catalysis and potential folding defects in in vitro studies of missense mutants associated with hereditary phosphoglucomutase 1 deficiency," was funded in part by the National Science Foundation (Award: MCB-1409898) and was published in The Journal of Biological Chemistry."

Editor's Note: For more information about Beamer's work, please visit: http://biochem.missouri.edu/features/ff-beamer-vandoren/index.php

http://medicine.missouri.edu/news/0061.php

http://coas.missouri.edu/news/2014/beamer.shtml

[Attachments] See images for this press release:

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

2014-11-11

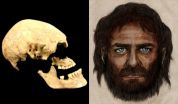

What if you researched your family's genealogy, and a mysterious stranger turned out to be an ancestor?

That's the surprising feeling had by a team of scientists who peered back into Europe's murky prehistoric past thousands of years ago. With sophisticated genetic tools, supercomputing simulations and modeling, they traced the origins of modern Europeans to three distinct populations.

The international research team published their September 2014 results in the journal Nature.

XSEDE, the Extreme Science and Engineering Discovery Environment, provided the computational ...

2014-11-11

Reston, Va. (November 11, 2014) - A novel study demonstrates the potential of a novel molecular imaging drug to detect and visualize early prostate cancer in soft tissue, lymph nodes and bone. The research, published in the November issue of the Journal of Nuclear Medicine, compares the biodistribution and tumor uptake kinetics of two Tc-99m labeled ligands, MIP-1404 and MIP-1405, used with SPECT and planar imaging.

Prostate cancer is the most commonly diagnosed non-skin cancer in the United States, and it is second only to lung cancer as the leading cause of cancer ...

2014-11-11

If you're a native of rural Mozambique who contracts HIV and becomes symptomatic, before seeking clinical testing and treatment, you'll likely consult a traditional healer.

Your healer may well conclude that your complaints are caused by a curse, perhaps placed upon you by a neighbor or by the spirit of an ancestor. To help you battle your predicament, the healer will likely cut your skin with a razor blade and rub medicinal herbs into the cut.

A recent survey of symptomatic HIV-positive people in rural Mozambique, led by Carolyn Audet, Ph.D., M.A., assistant professor ...

2014-11-11

New research from the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health suggests that HIV-infected adults are at a higher risk for developing heart attacks, kidney failure and cancer. But, contrary to what many had believed, the researchers say these illnesses are occurring at similar ages as adults who are not infected with HIV.

The findings appeared online last month in the journal Clinical Infectious Diseases.

Researchers say these findings can help reassure HIV-infected patients and their health care providers.

"We did not find conclusive evidence to suggest that ...

2014-11-11

New Haven, Conn.--The phrase "tears of joy" never made much sense to Yale psychologist Oriana Aragon. But after conducting a series of studies of such seemingly incongruous expressions, she now understands better why people cry when they are happy.

"People may be restoring emotional equilibrium with these expressions," said Aragon, lead author of work to be published in the journal Psychological Science. "They seem to take place when people are overwhelmed with strong positive emotions, and people who do this seem to recover better from those strong emotions."

There ...

2014-11-11

With both wolf proposals shot down by Michigan voters on election day, the debate over managing and hunting wolves is far from over.

A Michigan State University study, appearing in a recent issue of the Journal of Wildlife Management, identifies the themes shaping the issue and offers some potential solutions as the debate moves forward.

The research explored how different sides of the debate view power imbalances among different groups and the role that scientific knowledge plays in making decisions about hunting wolves. These two dimensions of wildlife management ...

2014-11-11

PHILADELPHIA (Nov. 11, 2014) - Federal laws explicitly addressing post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) have overwhelmingly focused on the needs of military personnel and veterans, according to a new analysis published in the Journal of Traumatic Stress.

The study, authored by Jonathan Purtle, DrPH, an assistant professor at the Drexel University School of Public Health, is the first to examine how public policy has been used to address psychological trauma and PTSD in the U.S., providing a glimpse of how lawmakers think about these issues.

Purtle found that in federal ...

2014-11-11

CHAMPAIGN, Ill. -- When munched by grazing animals (or mauled by scientists in the lab), some herbaceous plants overcompensate - producing more plant matter and becoming more fertile than they otherwise would. Scientists say they now know how these plants accomplish this feat of regeneration.

They report their findings in the journal Molecular Ecology.

Their study is the first to show that a plant's ability to dramatically rebound after being cut down relies on a process called genome duplication, in which individual cells make multiple copies of all of their genetic ...

2014-11-11

November 11, 2014--In recent years, many lakes in the upper Midwest have been experiencing unprecedented algae blooms. These blooms threaten fish and affect recreational activities. A key culprit implicated in overgrowth of algae in lakes is phosphorus (P). Lake Pepin, located on the Minnesota/Wisconsin border, has seen increasing phosphorus concentrations over time. Researchers are now trying to identify upstream factors that could explain this increase.

Satish Gupta, a University of Minnesota professor, and Ashley Grundtner, recently published a paper about their research ...

2014-11-11

Washington, D.C.--A two-person team of Carnegie's Scott Sheppard and Chadwick Trujillo of the Gemini Observatory has discovered a new active asteroid, called 62412, in the Solar System's main asteroid belt between Mars and Jupiter. It is the first comet-like object seen in the Hygiea family of asteroids. Sheppard will present his team's findings at the American Astronomical Society's Division of Planetary Sciences meeting and participate on Tuesday, November 11, in a press conference organized by the society.

Active asteroids are a newly recognized phenomenon. 62412 ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

[Press-News.org] MU researchers offer first analysis of new human glucose disorder

Findings are informing human research into rare, sometimes fatal glycogen storage disease