Self-doping may be the key to superconductivity in room temperature

2014-11-13

(Press-News.org) Swedish materials researchers at Linköping and Uppsala University and Chalmers University of Technology, in collaboration with researchers at the Swiss Synchrotron Light Source (SLS) in Switzerland investigated the superconductor YBa2Cu3O7-x (abbreviated YBCO) using advanced X-ray spectroscopy.

Their findings are published in the Nature journal Science Reports.

YBCO is a well-known ceramic copper-based material that can conduct electricity without loss (superconductivity) when it is cooled below its critical temperature Tc=-183° C. Since the resistance and energy losses are zero in superconductors, there exist many technologically interesting and energy-saving electrical applications as well as benefits to the transport industry. Electromagnets in electric motors can be made smaller with stronger magnetic fields that are more powerful yet consume less energy; magnetic levitating trains that exploit superconductor technology can reach higher speeds by avoiding friction against rails.

On the other hand, the necessity of cooling these materials to low temperatures remains to be an obstacle one would like to eliminate. Therefore, one of the major objectives of superconductor research is trying to find a material that is superconducting at room temperature. However, the mechanism that underlies high-temperature superconductivity is still not entirely understood. In this work, the researchers have made a discovery that may shed new light on this phenomenon. X-ray absorption spectroscopy (XAS) and resonant inelastic X-ray scattering (RIXS) was used for measuring YBCO at room temperature and at -258° C, which is far below Tc.

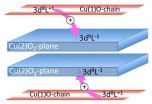

What makes YBCO special as a superconductor is that it is made up of two types of structural units, i.e. stacked "planes" of copper oxide, assumed to carry the superconducting current, but also separate "chains" of copper oxide in between. The role of the chains in YBCO has puzzled scientists ever since the discovery of its superconducting properties in 1987. One had realized early on that Tc can be influenced in the material synthesis procedure by varying the "oxygen doping", and thus the length of the chains.

It has long been assumed that the doping level of the material was solely determined by the structure of the chains at the time of synthesis. By contrast, the new experimental results show that the chains in YBCO react to cooling by supplying the copper oxide planes with positive charge (electron-hole), a mechanism called self-doping. By combining RIXS and model calculations, the researchers also found that self-doping is accompanied by changes in the copper-oxygen bonds that link the planes with the chains.

This groundbreaking discovery of self doping in YBCO challenges the traditional understanding of the mechanism of superconductivity in copper-based high-temperature superconductors, which assumes a constant doping level in the copper oxide planes. Some previous temperature-dependent experiments will now have to be re-evaluated in this new light, and thereby help us come closer to finally solving the riddle of high temperature superconductivity. Next, the researchers plan to conduct a more detailed temperature dependent study to determine if restructuring and redistribution of the orbital occupation occurs exactly at the phase transition to superconductivity or if it already occurs at a higher temperature in the so-called pseudogap region.

INFORMATION:

Article: Self-doping processes between planes and chains in the metal-to-superconductor transition of YBa2Cu3O6.9; M. Magnuson, T. Schmitt, V.N. Strocov, J. Schlappa, A.S. Kalabukhov and L.-C. Duda; Scientific Reports 4, 717 (2014).

DOI: 10.1038 / srep07017, Published: November 12, 2014.

[Attachments] See images for this press release:

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

2014-11-13

People on the autistic spectrum may struggle to recognise social cues, unfamiliar people or even someone's gender because of an inability to interpret changing facial expressions, new research has found.

According to the study by academics at Brunel University London, adults with autism spectrum disorders (ASD), though able to recognise static faces, struggle with tasks that require them to discriminate between sequences of facial motion or to use facial motion as a cue to identity.

The research supports previous evidence to suggest that impairments in perceiving biological ...

2014-11-13

Membranes are thin walls that surround cells and protect their interior from the environment. These walls are composed of phospholipids, which, due to their amphiphilic nature, form bilayers with dis-tinct chemical properties: While the outward-facing headgroups are charged, the core of the bilayer is hydrophobic, which prevents charged molecules from passing through. The controlled flow of ions across the membrane, which is essential for the transmission of nerve impulses, is facilitated by ion channels, membrane proteins that provide gated pathways for ions. Analogous ...

2014-11-13

A cat always lands on its feet. At least, that's how the adage goes. Karen Liu hopes that in the future, this will be true of robots as well.

To understand the way feline or human behavior during falls might be applied to robot landings, Liu, an associate professor in the School of Interactive Computing (IC) at Georgia Tech, delved into the physics of everything from falling cats to the mid-air orientation of divers and astronauts.

In research presented at the 2014 IEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS), Liu shared her studies of mid-air ...

2014-11-13

Weather, which changes day-to-day due to constant fluctuations in the atmosphere, and climate, which varies over decades, are familiar. More recently, a third regime, called "macroweather," has been used to describe the relatively stable regime between weather and climate.

A new study by researchers at McGill University and UCL finds that this same three-part pattern applies to atmospheric conditions on Mars. The results, published in Geophysical Research Letters, also show that the sun plays a major role in determining macroweather.

The research promises to advance ...

2014-11-13

Duchenne muscular dystrophy is the most common neuromuscular disease of children (affecting 1 boy in 3500-5000 births). It is caused by a genetic defect in the DMD gene residing on the X chromosome, which results in the absence of the dystrophin protein essential to the proper functioning of muscles.

The treatment being developed by researchers at Atlantic Gene Therapies, Généthon and the Institute of Myology, is based on the use of an AAV vector (Adeno Associated Virus) carrying a transgene for the skipping of a specific exon which allows functional dystrophin ...

2014-11-13

After graphene was first produced in the lab in 2004, thousands of laboratories began developing graphene products worldwide. Researchers were amazed by its lightweight and ultra-strong properties. Ten years later, scientists now search for other materials that have the same level of potential.

"We continue to work with graphene, and there are some applications where it works very well," said Mark Hersam, the Bette and Neison Harris Chair in Teaching Excellence at Northwestern University's McCormick School of Engineering and Applied Science, who is a graphene expert. ...

2014-11-13

High blood pressure - already a massive hidden killer in Nigeria - is set to sharply rise as the country adopts western lifestyles, a study suggests.

Researchers who conducted the first up-to-date nationwide estimate of the condition in Nigeria warn that this will strain the country's already-stretched health system.

Increased public awareness, lifestyle changes, screening and early detection are vital to tackle the increasing threat of the disease, they say.

High blood pressure - also known as hypertension - is twice as high in Nigeria compared with other East ...

2014-11-13

Researchers at The University of Texas have found that compared to Caucasian Americans, African Americans have impaired blood flow regulation in the brain that could contribute to a greater risk of cerebrovascular diseases such as stroke, transient ischaemic attack ("mini stroke"), subarachnoid haemorrhage or vascular dementia. These findings were published in Experimental Physiology, the journal of The Physiological Society.

Cerebrovascular diseases can result from reduced blood flow in affected areas of the brain. It is still unclear why African Americans are at higher ...

2014-11-13

Needles almost too small to be seen with the unaided eye could be the basis for new treatment options for two of the world's leading eye diseases: glaucoma and corneal neovascularization.

The microneedles, ranging in length from 400 to 700 microns, could provide a new way to deliver drugs to specific areas within the eye relevant to these diseases. By targeting the drugs only to specific parts of the eye instead of the entire eye, researchers hope to increase effectiveness, limit side effects, and reduce the amount of drug needed.

For glaucoma, which affects about 2.2 ...

2014-11-13

(PHILADELPHIA) - Glioblastoma is the most common aggressive primary brain tumor, and despite advances in standard treatment, the median survival is about 15 months (compared to 4 months without treatment). Researchers at Thomas Jefferson University have been working on a cancer vaccine that would extend that survival by activating the patient's immune system to fight the brain tumor. A study published online November 13th in the journal Cancer Immunology, Immunotherapy drilled down to the cellular and molecular mechanisms behind the vaccine, paving the way for further development ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

[Press-News.org] Self-doping may be the key to superconductivity in room temperature