(Press-News.org) The scientists showed that the Parkin protein functions to repair or destroy damaged nerve cells, depending on the degree to which they are damaged

People living with Parkinson's disease often have a mutated form of the Parkin gene, which may explain why damaged, dysfunctional nerve cells accumulate

Dublin, Ireland, November 13th, 2014 - Scientists at Trinity College Dublin have made an important breakthrough in our understanding of Parkin - a protein that regulates the repair and replacement of nerve cells within the brain. This breakthrough generates a new perspective on how nerve cells die in Parkinson's disease. The Trinity research group, led by Smurfit Professor of Medical Genetics, Professor Seamus Martin, has just published its findings in the internationally renowned, peer-reviewed Cell Press journal, Cell Reports.

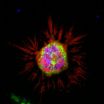

Although mutation of Parkin has been known to lead to an early onset form of Parkinson's for many years, understanding what it actually did within cells has been difficult to solve. Now, Professor Martin and colleagues have discovered that in response to specific types of cell damage, Parkin can trigger the self-destruction of 'injured' nerve cells by switching on a controlled process of 'cellular suicide' called apoptosis.

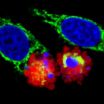

Using cutting-edge research techniques, the Martin laboratory, funded by Science Foundation Ireland, found that damage to mitochondria (which function as 'cellular battery packs') activates the Parkin protein, which results in one of two different outcomes - either self-destruction or a repair mode. Which outcome was chosen depended on the degree of damage suffered by the cellular battery packs.

Importantly, these new findings suggest that one of the problems in Parkinson's disease may be the failure to clear away sick nerve cells with faulty cellular battery packs, to make way for healthy replacements. Instead, sickly and dysfunctional nerve cells may accumulate, which effectively prevents the recruitment of fresh replacements.

Commenting on the findings, Professor Martin stated: "This discovery is surprising and turns on its head the way we thought that Parkin functions. Until now, we have thought of Parkin as a brake on cell death within nerve cells, helping to delay their death. However, our new data suggests the contrary: Parkin may in fact help to weed out injured and sick nerve cells, which probably facilitates their replacement. This suggests that Parkinson's disease could result from the accumulation of defective neurons due to the failure of this cellular weeding process."

Professor Martin also added: "We are very grateful for the support of Science Foundation Ireland, who funded this research. This work represents an excellent example of how basic research leads to fundamental breakthroughs in our understanding of how diseases arise. Without such knowledge, it would be very difficult to develop new therapies."

INFORMATION:

The work was carried out in Trinity's School of Genetics and Microbiology. The research team was led by Professor Martin and included Trinity PhD student Richard Carroll and Research Fellow Dr Emilie Hollville. The Trinity research team is internationally recognised for its work on the regulation of cell death.

For media queries, please contact:

Thomas Deane, Press Officer for the Faculty of Engineering, Mathematics and Science, Trinity College Dublin, at deaneth@tcd.ie or Tel: +353-1-896-4685 / +353-85-131-5587

Smurfit Professor of Medical Genetics, Seamus Martin, Trinity College Dublin, at martinsj@tcd.ie

Notes to the editor:

1. Full title of the journal article is: 'Parkin Sensitizes toward Apoptosis Induced by Mitochondrial Depolarization through Promoting Degradation of Mcl-1, Cell Press journal, Cell Reports

About Trinity College Dublin

Trinity College Dublin, founded in 1592 is Ireland's oldest university and today has a vibrant community of 17,000 students. It is recognised internationally as Ireland's premier university. Cutting edge research, technology and innovation places the university at the forefront of higher education in Ireland and globally. It encompasses all major academic disciplines, and is committed to world-class teaching and research across the range of disciplines in the arts, humanities, engineering, science, social and health sciences.

Trinity is Ireland's leading university across all international rankings, and was ranked 61st globally in 2013 QS World University Ranking http://www.tcd.ie.

High-resolution images and captions are available, and can be accessed from this Dropbox folder: https://www.dropbox.com/sh/cyd6sf5eazbqsr0/AAB7uFMeI9-CbxVbJ4L7L3Cfa?dl=0

There are no approved treatments or preventatives against Ebola virus disease, but investigators have now designed peptides that mimic the virus' N-trimer, a highly conserved region of a protein that's used to gain entry inside cells.

The team showed that the peptides can be used as targets to help researchers develop drugs that might block Ebola virus from entering into cells.

"In contrast to the most promising current approaches for Ebola treatment or prevention, which are species-specific, our 'universal' target will enable the selection of broad-spectrum inhibitors ...

In a study of middle-aged men who were overweight, researchers found that if a man's parents were older at the time of his birth, he was more likely to have lower blood pressure, more favorable cholesterol levels, and improved glucose metabolism. It's unknown whether the beneficial effect was due to having an older mother, an older father, or both.

Additional studies are necessary to help shed light on the effects of parental age at childbirth on the metabolism of men and women. "In particular, more research is required to understand whether these effects are due to ...

In a study that looked at what factors might affect whether or not a patient receives intensive medical procedures in the last 6 months of life, investigators found that older age, Alzheimer's disease, cancer, living in a nursing home, and having an advance directive were associated with a lower likelihood of undergoing an intensive procedure. In contrast, living in a region with higher hospital care intensity and black race each doubled a patient's likelihood of undergoing an intensive procedure.

"It's pretty striking the extent to which nonclinical factors--such as ...

Preeclampsia, a late-pregnancy disorder that is characterized by high blood pressure and organ damage, may be caused by problems related to meeting the oxygen demands of the growing fetus, experts say in a new Anaesthesia paper.

Left untreated, preeclampsia can lead to serious--even fatal--complications for a pregnant woman and her baby. The new theory challenges the current view that pre-eclampsia is caused by a problem with the placenta. "When the fetus is not getting enough oxygen and nutrients for its growth--due to conditions in the mother, conditions in the placenta ...

Investigators recently set out to consider whether homicides involving social networking sites were unique and worthy of labels such as 'Facebook Murder', and to explore the ways in which perpetrators had used such sites in the homicides they had committed.

The cases they identified were not collectively unique or unusual when compared with general trends and characteristics--certainly not to a degree that would necessitate the introduction of a new category of homicide or a broad label like 'Facebook Murder'.

"Victims knew their killers in most cases, and the crimes ...

Stanching the free flow of blood from an injury remains a holy grail of clinical medicine. Controlling blood flow is a primary concern and first line of defense for patients and medical staff in many situations, from traumatic injury to illness to surgery. If control is not established within the first few minutes of a hemorrhage, further treatment and healing are impossible.

At UC Santa Barbara, researchers in the Department of Chemical Engineering and at Center for Bioengineering (CBE) have turned to the human body's own mechanisms for inspiration in dealing with the ...

Researchers at the University of Texas Medical Branch at Galveston, in collaboration with The University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston (UTHealth), Baylor College of Medicine and the Georgia Regents University, report for the first time that the cholesterol-lowering drug simvastatin inhibits the growth of human uterine fibroid tumors. These new data are published online and scheduled to appear in the January print edition of the Journal of Biological Chemistry.

Statins, such as simvastatin, are commonly prescribed to lower high cholesterol levels. Statins ...

A study from the Institute of Food Research has shown that Campylobacter's persistence in food processing sites and the kitchen is boosted by 'chicken juice.'

Organic matter exuding from chicken carcasses, "chicken juice", provides these bacteria with the perfect environment to persist in the food chain. This emphasises the importance of cleaning surfaces in food preparation, and may lead to more effective ways of cleaning that can reduce the incidence of Campylobacter.

The study was led by Helen Brown, a PhD student supervised by Dr Arnoud van Vliet at IFR, which is ...

The strains of enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli (ETEC) that infect adults and children in Asia, Africa, and the Americas, have notably similar toxins and virulence factors, according to research published ahead of print in the Journal of Bacteriology. That bodes well for vaccine development, says corresponding author Åsa Sjöling, now of the Karolinska Institutet, Stockholm, Sweden. ETEC infects 400 million people annually, or 5.3 percent of the world's population, killing 400,000.

In the study, Sjöling et al. set out to determine whether the heat labile ...

Frightening experiences do not quickly fade from memory. A team of researchers under the guidance of the University of Bonn Hospital has now been able to demonstrate in a study that the bonding hormone oxytocin inhibits the fear center in the brain and allows fear stimuli to subside more easily. This basic research could also usher in a new era in the treatment of anxiety disorders. The study has already appeared in advance online in the journal "Biological Psychiatry". The print edition will be available in a few weeks.

Significant fear becomes deeply entrenched in memory. ...