(Press-News.org) Time ravages mountains, as it does people. Sharp features soften, and bodies grow shorter and rounder. But under the right conditions, some mountains refuse to age. In a new study, scientists explain why the ice-covered Gamburtsev Mountains in the middle of Antarctica looks as young as they do.

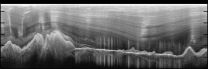

The Gamburtsevs were discovered in the 1950s, but remained unexplored until scientists flew ice-penetrating instruments over the mountains 60 years later. As this ancient hidden landscape came into focus, scientists were stunned to see the saw-toothed and towering crags of much younger mountains. Though the Gamburtsevs are contemporaries of the largely worn-down Appalachians, they looked more like the Rockies, which are nearly 200 million years younger.

More surprising still, the scientists discovered a vast network of lakes and rivers at the mountains' base. Though water usually speeds erosion, here it seems to have kept erosion at bay. The reason, researchers now say, has to do with the thick ice that has entombed the Gamburtsevs since Antarctica went into a deep freeze 35 million years ago.

"The ice sheet acts like an anti-aging cream," said the study's lead author, Timothy Creyts, a geophysicist at Columbia University's Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory. "It triggers a series of thermodynamic processes that have almost perfectly preserved the Gamburtsevs since ice began spreading across the continent."

The study, which appears in the latest issue of the journal Geophysical Research Letters, explains how the blanket of ice covering the Gamburtsevs has preserved its rugged ridgelines.

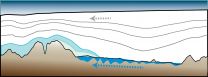

Snow falling at the surface of the ice sheet draws colder temperatures down, closer to protruding peaks in a process called divergent cooling. At the same time, heat radiating from bedrock beneath the ice sheet melts ice in the deep valleys to form rivers and lakes. As rivers course along the base of the ice sheet, high pressures from the overlying ice sheet push water up valleys in reverse. This uphill flow refreezes as it meets colder temperature from above. Thus, ridgelines are cryogenically preserved.

The oldest rocks in the Gamburtsevs formed more than a billion years ago, in the collision of several continents. Though these prototype mountains eroded away, a lingering crustal root became reactivated when the supercontinent Gondwana ripped apart, starting about 200 million years ago. Tectonic forces pushed the land up again to form the modern Gamburtsevs, which range across an area the size of the Alps. Erosion again chewed away at the mountains until earth entered a cooling phase 35 million years ago. Expanding outward from the Gamburtsevs, a growing layer of ice joined several other nucleation points to cover the entire continent in ice.

The researchers say that the mechanism that stalled aging of the Gamburtsevs at higher elevations may explain why some ridgelines in the Torngat Mountains on Canada's Labrador Peninsula and the Scandinavian Mountains running through Norway, Sweden and Finland appear strikingly untouched. Massive ice sheets covered both landscapes during the last ice age, which peaked about 20,000 years ago, but many high-altitude features bear little trace of this event.

"The authors identify a mechanism whereby larger parts of mountains ranges in glaciated regions--not just Antarctica--could be spared from erosion," said Stewart Jamieson, a glaciologist at Durham University who was not involved in the study. "This is important because these uplands are nucleation centers for ice sheets. If they were to gradually erode during glacial cycles, they would become less effective as nucleation points during later ice ages."

Ice sheet behavior, then, may influence climate change in ways that scientists and computer models have yet to appreciate. As study coauthor Fausto Ferraccioli, head of the British Antarctic Survey's airborne geophysics group, put it: "If these mountains in interior East Antarctica had been more significantly eroded then the ice sheet itself

may have had a different history."

INFORMATION:

Other Authors

Hugh Carr and Tom Jordan of the British Antarctic Survey; Robin Bell, Michael Wolovick and Nicholas Frearson of Lamont-Doherty; Kathryn Rose of University of Bristol; Detlef Damaske of Germany's Federal Institute for Geosciences and Natural Resources; David Braaten of Kansas University; and Carol Finn of the U.S. Geological Survey.

Copies of the paper, "Freezing of ridges and water networks preserves the Gamburtsev Subglacial Mountains for millions of years," are available from the authors.

Scientist Contact

Tim Creyts

845-365-8368

tcreyts@ldeo.columbia.edu

Fpr more information, contact Kim Martineau, Science Writer, Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory.

The Earth Institute, Columbia University mobilizes the sciences, education and public policy to achieve a sustainable earth. http://www.earth.columbia.edu.

Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory seeks fundamental knowledge about the origin, evolution and future of the natural world. Its scientists study the planet from its deepest interior to the outer reaches of its atmosphere, on every continent and in every ocean, providing a rational basis for the difficult choices facing humanity. http://www.ldeo.columbia.edu

Researchers from China, the Philippines and LSTM have today published a new systematic review of reminder systems to improve patient adherence to tuberculosis (TB) treatment. Reminder systems include prompts in advance of a forthcoming appointment to help ensure the patients attend, and also actions when people miss an appointment, such as phoning them or arranging a home visit. This review is the latest in a suite of reviews produced by authors from the Cochrane Infectious Diseases Group, hosted at LSTM, evaluating interventions to improve adherence to TB treatment. Effective ...

Washington, D.C. - November 19, 2014 - Lumosity is presenting new research today at the 2014 Society for Neuroscience conference on how lifestyle factors such as sleep, mood and time of day impact cognitive gameplay performance. The study, titled "Estimating sleep, mood and time of day effects in a large database of human cognitive performance," analyzed over 60 million data points from 61,407 participants and found that memory, speed, and flexibility tasks peaked in the morning, while crystallized knowledge tasks such as arithmetic and verbal fluency peaked in the afternoon. ...

An international team of scientists, coordinated by a researcher from the U. of Granada, has found that seed dormancy (a property that prevents germination under non-favourable conditions) was a feature already present in the first seeds, 360 million years ago.

Seed dormancy is a phenomenon that has intrigued naturalists for decades, since it conditions the dynamics of natural vegetation and agricultural cycles. There are several types of dormancy, and some of them are modulated by environmental conditions in more subtle ways than others.

In an article published in the ...

Quasars are galaxies with very active supermassive black holes at their centres. These black holes are surrounded by spinning discs of extremely hot material that is often spewed out in long jets along their axes of rotation. Quasars can shine more brightly than all the stars in the rest of their host galaxies put together.

A team led by Damien Hutsemékers from the University of Liège in Belgium used the FORS instrument on the VLT to study 93 quasars that were known to form huge groupings spread over billions of light-years, seen at a time when the Universe ...

PROVIDENCE, R.I. [Brown University] -- A widely presumed problem of aging is that the brain becomes less flexible -- less plastic -- and that learning may therefore become more difficult. A new study led by Brown University researchers contradicts that notion with a finding that plasticity did occur in seniors who learned a task well, but it occurred in a different part of the brain than in younger people.

When many older subjects learned a new visual task, the researchers found, they unexpectedly showed a significantly associated change in the white matter of the brain. ...

Professor Dan Davis and his team at the Manchester Collaborative Centre for Inflammation Research, working in collaboration with global healthcare company GSK, investigated how different types of immune cells communicate with each other - and how they kill cancerous or infected cells. Their research has been published in Nature Communications.

Professor Davis says: "We studied the immune system and then stumbled across something that may explain why some drugs don't work as well as hoped. We found that immune cells secrete molecules to other cells across a very small ...

A recent study by an Indiana University researcher has found that adolescents' alcohol use is influenced by their close friends' use, regardless of how much alcohol they think their general peers consume.

Jonathon Beckmeyer, assistant professor in the Department of Applied Health Science at the IU School of Public Health-Bloomington and author of the study, said his research generally focuses on the onset of teen alcohol use and how their social relationships shape those experiences.

"We've known for a long time that friends and peers have an influence on individual ...

SAN FRANCISCO, Nov. 19, 2014 -- Hox genes are master body-building genes that specify where an animal's head, tail and everything in between should go. There's even a special Hox gene program that directs the development of limbs and fins, including specific modifications such as the thumb in mice and humans. Now, San Francisco State University researchers show that this fin- and limb-building genetic program is also utilized during the development of other vertebrate features.

The discovery means this ancient genetic program is employed in a variety of features beyond ...

A new study, published online in Brain: A Journal of Neurology today, followed 43,368 individuals in Sweden for an average of 12.6 years to examine the impact of physical activity on Parkinson's disease risk. It was found that "a medium amount" of physical activity lowers the risk of Parkinson's disease.

Karin Wirdefeldt of the Karolinska Institutet in Stockholm and her colleagues used the Swedish National March Cohort to analyse comprehensive information on physical activity of all kinds. They assessed household and commuting activity, occupational activity, leisure ...

A new study led by researchers at King's College London in collaboration with the US Consortium of Food Allergy Research and the University of Dundee has found a strong link between environmental exposure to peanut protein during infancy (measured in household dust) and an allergic response to peanuts in children who have eczema early in life.

Around two per cent of school children in the UK and the US are allergic to peanuts. Severe eczema in early infancy has been linked to food allergies, particularly peanut allergy.

The study, published in the Journal of Allergy ...