Mere expectation of treatment can improve brain activity in Parkinson's patients

2014-11-25

(Press-News.org) Learning-related brain activity in Parkinson's patients improves as much in response to a placebo treatment as to real medication, according to a new study by researchers at the University of Colorado Boulder and Columbia University.

Past research has shown that while Parkinson's disease is a neurological reality, the brain systems involved may also be affected by a patient's expectations about treatment. The new study, published in the journal Nature Neuroscience, explains how the placebo treatment -- when patients believe they have received medication when they have not -- works in people with Parkinson's disease by activating dopamine-rich areas in the brain.

"The findings highlight the power of expectations to drive changes in the brain," said Tor Wager, an associate professor of psychology and neuroscience at CU-Boulder and a co-author of the study. "The research highlights important links between psychology and medicine."

Parkinson's patients have difficulty with "reward learning," the brain's ability to associate actions with rewards and make motivated decisions to pursue positive outcomes. Reward learning is supported by neurons that emit dopamine when an action, like pushing a particular button, leads to a reward, like receiving money.

Reward learning is impaired in Parkinson's patients because the disease causes the neurons that release dopamine to die. Parkinson's patients can be treated for this condition with a medication that increases the dopamine in the brain, L-dopa.

For the new study, the research team -- which also includes Columbia University researchers Liane Schmidt, Erin Kendall Braun and Daphna Shohamy -- used functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging (fMRI) to scan the brains of 18 Parkinson's patients as they played a computer game that measures reward learning. In the game, participants discover through trial and error which of two symbols is more likely to lead to a better outcome, in this case a small monetary reward or simply not losing any money.

The Parkinson's patients played the game three times: when they were not taking any medication, when they took real medication (dissolved in orange juice), and when they took a placebo, which consisted of drinking orange juice that they thought contained their medication. The researchers found that the dopamine-rich areas of the brain associated with reward learning -- the striatum and the ventromedial prefrontal cortex -- became equally active when patients took either the real medication or the placebo treatment.

"This finding demonstrates a link between brain dopamine, expectation and learning," Wager said. "Recognizing that expectation and positive emotions matter has the potential to improve the quality of life for Parkinson's patients, and may also offer clues to how placebos may be effective in treating other types of diseases."

INFORMATION:

The study was funded by the Michael J. Fox Foundation for Parkinson's Research.

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

2014-11-25

Endangered Snake River sockeye salmon are regaining the fitness of their wild ancestors, with naturally spawned juvenile sockeye migrating to the ocean and returning as adults at a much higher rate than others released from hatcheries, according to a newly published analysis. The analysis indicates that the program to save the species has succeeded and is now shifting to rebuilding populations in the wild.

Biologists believe the increased return rate of sockeye spawned naturally by hatchery-produced parents is high enough for the species to eventually sustain itself in ...

2014-11-25

MAYWOOD, Il. - An award-winning study by a Loyola University Chicago Stritch School of Medicine researcher has documented how homeless, mentally ill women in India face a vicious cycle:

During psychotic episodes, they wander away from home, sometimes for long distances, and wind up in homeless shelters. They then are returned to their families before undergoing sufficient psychosocial rehabilitation to deal with their illness. Consequently, they suffer mental illness relapses and wind up homeless again.

"The study illustrates how there must be a balance between reintegrating ...

2014-11-25

While the turkey you eat on Thursday will bring your stomach happiness and could probably kick-start an afternoon nap, it may also save your life one day.

That's because the biological machinery needed to produce a potentially life-saving antibiotic is found in turkeys. Looks like there is one more reason to be grateful this Thanksgiving.

"Our research group is certainly thankful for turkeys," said BYU microbiologist Joel Griffitts, whose team is exploring how the turkey-born antibiotic comes to be. "The good bacteria we're studying has been keeping turkey farms healthy ...

2014-11-25

How is it that vultures can live on a diet of carrion that would at least lead to severe food-poisoning, and more likely kill most other animals? This is the key question behind a recent collaboration between a team of international researchers from Denmark's Centre for GeoGenetics and Biological Institute at the University of Copenhagen, Aarhus University, the Technical University of Denmark, Copenhagen Zoo and the Smithsonian Institution in the USA. An "acidic" answer to this question is now published in the scientific journal Nature Communications.

When vultures eat ...

2014-11-25

Who knew Blu-ray discs were so useful? Already one of the best ways to store high-definition movies and television shows because of their high-density data storage, Blu-ray discs also improve the performance of solar cells -- suggesting a second use for unwanted discs -- according to new research from Northwestern University.

An interdisciplinary research team has discovered that the pattern of information written on a Blu-ray disc -- and it doesn't matter if it's Jackie Chan's "Supercop" or the cartoon "Family Guy" -- works very well for improving light absorption across ...

2014-11-25

New York, NY, November 25, 2014 - Testosterone (T) therapy is routinely used in men with hypogonadism, a condition in which diminished function of the gonads occurs. Although there is no evidence that T therapy increases the risk of prostate cancer (PCa), there are still concerns and a paucity of long-term data. In a new study in The Journal of Urology®, investigators examined three parallel, prospective, ongoing, cumulative registry studies of over 1,000 men. Their analysis showed that long-term T therapy in hypogonadal men is safe and does not increase the risk of ...

2014-11-25

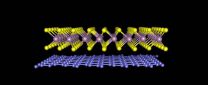

LAWRENCE -- Physicists at the University of Kansas have fabricated an innovative substance from two different atomic sheets that interlock much like Lego toy bricks. The researchers said the new material -- made of a layer of graphene and a layer of tungsten disulfide -- could be used in solar cells and flexible electronics. Their findings are published today by Nature Communications.

Hsin-Ying Chiu, assistant professor of physics and astronomy, and graduate student Matt Bellus fabricated the new material using "layer-by-layer assembly" as a versatile bottom-up nanofabrication ...

2014-11-25

The bacterium Helicobacter pylori is strongly associated with gastric ulcers and cancer. To combat the infection, researchers at University of California, San Diego School of Medicine and Jacobs School of Engineering developed LipoLLA, a therapeutic nanoparticle that contains linolenic acid, a component in vegetable oils. In mice, LipoLLA was safe and more effective against H. pylori infection than standard antibiotic treatments.

The results are published online Nov. 24 in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

"Current H. pylori treatments are facing ...

2014-11-25

Medford/Somerville, Mass--Researchers in human genetics have known that long nucleotide repeats in DNA lead to instability of the genome and ultimately to human hereditary diseases such Freidreich's ataxia and Huntington's disease.

Scientists have believed that the lengthening of those repeats occur during DNA replication when cells divide or when the cellular DNA repair machinery gets activated. Recently, however, it became apparent that yet another process called transcription, which is copying the information from DNA into RNA, could also been involved.

A Tufts ...

2014-11-25

Researchers at the University of Leeds have shed light on a gene mutation linked to autistic traits.

The team already knew that some people with autism were deficient in a gene called neurexin-II. To investigate whether the gene was associated with autism symptoms, the Leeds team studied mice with the same defect.

They found behavioural features that were similar to autism symptoms, including a lack of sociability or interest in other mice.

Dr Steven Clapcote, Lecturer in Pharmacology in the University's Faculty of Biological Sciences, who led the study published ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

[Press-News.org] Mere expectation of treatment can improve brain activity in Parkinson's patients