(Press-News.org) In recent years it has been established that copper plays an essential role in the health of the human brain. Improper copper oxidation has been linked to several neurological disorders including Alzheimer's, Parkinson's, Menkes' and Wilson's. Copper has also been identified as a critical ingredient in the enzymes that activate the brain's neurotransmitters in response to stimuli. Now a new study by researchers with the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE)'s Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (Berkeley Lab) has shown that proper copper levels are also essential to the health of the brain at rest.

"Using new molecular imaging techniques, we've identified copper as a dynamic modulator of spontaneous activity of developing neural circuits, which is the baseline activity of neurons without active stimuli, kind of like when you sleep or daydream, that allows circuits to rest and adapt," says Chris Chang, a faculty chemist with Berkeley Lab's Chemical Sciences Division who led this study. "Traditionally, copper has been regarded as a static metabolic cofactor that must be buried within enzymes to protect against the generation of reactive oxygen species and subsequent free radical damage. We've shown that dynamic and loosely bound pools of copper can also modulate neural activity and are essential for the normal development of synapses and circuits."

Chang , who also holds appointments with the University of California (UC) Berkeley's Chemistry Department and the Howard Hughes Medical Institute (HHMI), is the corresponding author of a paper that describes this study in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS). The paper is titled "Copper is an endogenous modulator of neural circuit spontaneous activity." Co-authors are Sheel Dodani, Alana Firl, Jefferson Chan, Christine Nam, Allegra Aron, Carl Onak, Karla Ramos-Torres, Jaeho Paek, Corey Webster and Marla Feller.

Although the human brain accounts for only two-percent of total body mass, it consumes 20-percent of the oxygen taken in through respiration. This high demand for oxygen and oxidative metabolism has resulted in the brain harboring the body's highest levels of copper, as well as iron and zinc. Over the past few years, Chang and his research group at UC Berkeley have developed a series of fluorescent probes for molecular imaging of copper in the brain.

"A lack of methods for monitoring dynamic changes in copper in whole living organisms has made it difficult to determine the complex relationships between copper status and various stages of health and disease," Chang said. "We've been designing fluorescent probes that can map the movement of copper in live cells, tissue or even model organisms, such as mice and zebra fish."

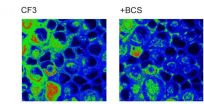

For this latest study, Chang and his group developed a fluorescent probe called Copper Fluor-3 (CF3) that can be used for one- and two-photon imaging of copper ions. This new probe allowed them to explore the potential contributions to cell signaling of loosely bound forms of copper in hippocampal neurons and retinal tissue.

"CF3 is a more hydrophilic probe compared to others we have made, so it gives more even staining and is suitable for both cells and tissue," Chang says. "It allows us to utilize both confocal and two-photon imaging methods when we use it along with a matching control dye (Ctrl-CF3) that lacks sensitivity to copper."

With the combination of CF3 and Ctrl-CF3, Chang and his group showed that neurons and neural tissue maintain stores of loosely bound copper that can be attenuated by chelation to create what is called a "labile copper pool." Targeted disruption of these labile copper pools by acute chelation or genetic knockdown of the copper ion channel known as CTR1 (for copper transporter 1) alters spontaneous neural activity in developing hippocampal and retinal circuits.

"We demonstrated that the addition of the copper chelator bathocuproine disulfonate (BCS) modulates copper signaling which translates into modulation of neural activity," Chang says. "Acute copper chelation as a result of additional BCS in dissociated hippocampal cultures and intact developing retinal tissue removed the copper which resulted in too much spontaneous activity."

The results of this study suggest that the mismanagement of copper in the brain that has been linked to Wilson's, Alzheimer's and other neurological disorders can also contribute to misregulation of signaling in cell−to-cell communications.

"Our results hold therapeutic implications in that whether a patient needs copper supplements or copper chelators depends on how much copper is present and where in the brain it is located," Chang says. "These findings also highlight the continuing need to develop molecular imaging probes as pilot screening tools to help uncover unique and unexplored metal biology in living systems."

INFORMATION:

This research was supported by the National Institutes of Health and the Howard Hughes Medical Institute.

Lincoln, Neb., Nov. 26, 2014 -- By solving a six-dimensional equation that had previously stymied researchers, University of Nebraska-Lincoln physicists have pinpointed the characteristics of a laser pulse that yields electron behavior they can predict and essentially control.

It's long been known that laser pulses of sufficient intensity can produce enough energy to eject electrons from their ultrafast orbits around an atom, causing ionization.

An international team led by the UNL researchers has demonstrated that the angles at which two electrons launch from a helium ...

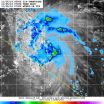

The Tropical Rainfall Measuring Mission or TRMM satellite provided rainfall data as Tropical Depression 21W was making landfall in the southern Philippines on Nov. 26.

TRMM revealed areas of heavy rainfall in fragmented bands east of the center of circulation, where rain was falling at more than 1 inch (25 mm) per hour. TRMM rainfall data was overlaid on infrared data from the Japan Meteorological Agency's MTSAT-1 satellite that showed Tropical Depression 21W's (TD21W) clouds extended from western Mindanao, east into the Philippine Sea.

On Nov. 26, there were a number ...

ST. LOUIS-- In research published in the medical journal Brain, Saint Louis University researcher Daniela Salvemini, Ph.D. and colleagues within SLU, the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and other academic institutions have discovered a way to block a pain pathway in animal models of chronic neuropathic pain including pain caused by chemotherapeutic agents and bone cancer pain suggesting a promising new approach to pain relief.

The scientific efforts led by Salvemini, who is professor of pharmacological and physiological sciences at SLU, demonstrated that turning on ...

Hamilton, ON (Nov. 26, 2014) - McMaster University researchers have found that current evidence does not support the routine use of minimally invasive surgery to remove herniated disc material pressing on the nerve root or spinal cord in the neck or lower back.

In comparing it with open surgery, they found that while minimally invasive surgery for cervical or lumbar discectomy may speed up recovery and reduce post-operative pain, it does not improve long-term function or reduce long-term extremity pain.

Minimally invasive surgery for discectomy also requires advanced ...

This news release is available in German. The human brain continuously collects information. However, we have only basic knowledge of how new experiences are converted into lasting memories. Now, an international team led by researchers of the University of Magdeburg and the German Center for Neurodegenerative Diseases (DZNE) has successfully determined the location, where memories are generated with a level of precision never achieved before. The team was able to pinpoint this location down to specific circuits of the human brain. To this end the scientists used a ...

The evolution of freshwater shrimps species living in both sides of Central America, isolated by the closure of Isthmus of Panama (3 million years ago) were studied by molecular tools. Despite the small likelihood of species crossing the Isthmus from one side to the other through the channel exist, the genetic isolation of them were maintained over the time and the separation of Pacific and Atlantic sister species still unchanged. Sister species refer to pairs of species that are genetically and morphologically closely related, but reproductively isolated.

The collection ...

A new paper, by Dr Stanley Blue, lecturer in Social Sciences at The University of Manchester, claims that there needs to be a shift in public health policy, with less focus on efforts to change individual behaviour and more attention on breaking social habits and practices that are blindly leading us into bad health.

Theories of practice and public health: understanding (un)healthy practices is published in the journal, Critical Public Health, and written by Dr Stanley Blue, lecturer at the School of Social Sciences, Prof Elizabeth Shove, of Lancaster University, Prof ...

CLEVELAND, Ohio (November 26, 2014)--Removing ovaries at hysterectomy does not increase a woman's risk of pelvic organ prolapse after menopause. In fact, removing ovaries lowers the risk of prolapse. This surprising finding from a Women's Health Initiative study was published online this week in Menopause, the journal of The North American Menopause Society (NAMS).

Whether to remove ovaries at hysterectomy for reasons other than cancer is a subject of hot debate. Removing them reduces the risk of breast cancer and dramatically reduces the risk of ovarian cancer. On the ...

For several years, it has been known that superfluid helium housed in reservoirs located next to each other acts collectively, even when the channels connecting the reservoirs are too narrow and too long to allow for substantial flow. A new theoretical model reveals that the phenomenon of mysterious communication "at a distance" between fluid reservoirs is much more common than previously thought.

Liquids in containers that are at a distance from each other may behave collectively, even if the channels connecting the reservoirs are so narrow and long that they prevent ...

Enzymes are macromolecular biological catalysists that lead most of chemical reactions in living organisms. The main focus of enzymology lies on enzymes themselves, whereas the role of water motions in mediating the biological reaction is often left aside owing to the complex molecular behavior. The groups of Martina Havenith (Cluster of Excellence RESOLV - Ruhr explores Solvation) and Irit Sagi (Weizmann Institue of Science, Israel) revised the classical enzymatic steady state theory by including long-lasting protein-water coupled motions into models of functional catalysis. ...