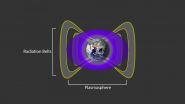

(Press-News.org) High above Earth's atmosphere, electrons whiz past at close to the speed of light. Such ultrarelativistic electrons, which make up the outer band of the Van Allen radiation belt, can streak around the planet in a mere five minutes, bombarding anything in their path. Exposure to such high-energy radiation can wreak havoc on satellite electronics, and pose serious health risks to astronauts.

Now researchers at MIT, the University of Colorado, and elsewhere have found there's a hard limit to how close ultrarelativistic electrons can get to the Earth. The team found that no matter where these electrons are circling around the planet's equator, they can get no further than about 11,000 kilometers from the Earth's surface -- despite their intense energy.

What's keeping this high-energy radiation at bay seems to be neither the Earth's magnetic field nor long-range radio waves, but rather a phenomenon termed "plasmaspheric hiss" -- very low-frequency electromagnetic waves in the Earth's upper atmosphere that, when played through a speaker, resemble static, or white noise.

Based on their data and calculations, the researchers believe that plasmaspheric hiss essentially deflects incoming electrons, causing them to collide with neutral gas atoms in the Earth's upper atmosphere, and ultimately disappear. This natural, impenetrable barrier appears to be extremely rigid, keeping high-energy electrons from coming no closer than about 2.8 Earth radii -- or 11,000 kilometers from the Earth's surface.

"It's a very unusual, extraordinary, and pronounced phenomenon," says John Foster, associate director of MIT's Haystack Observatory. "What this tells us is if you parked a satellite or an orbiting space station with humans just inside this impenetrable barrier, you would expect them to have much longer lifetimes. That's a good thing to know."

Foster and his colleagues, including lead author Daniel Baker of the University of Colorado, have published their results this week in the journal Nature.

Shields up

The team's results are based on data collected by NASA's Van Allen Probes -- twin crafts that are orbiting within the harsh environments of the Van Allen radiation belts. Each probe is designed to withstand constant radiation bombardment in order to measure the behavior of high-energy electrons in space.

The researchers analyzed the first 20 months of data returned by the probes, and observed an "exceedingly sharp" barrier against ultrarelativistic electrons. This barrier held steady even against a solar wind shock, which drove electrons toward the Earth in a "step-like fashion" in October 2013. Even under such stellar pressure, the barrier kept electrons from penetrating further than 11,000 kilometers above Earth's surface.

To determine the phenomenon behind the barrier, the researchers considered a few possibilities, including effects from the Earth's magnetic field and transmissions from ground-based radios.

For the former, the team focused in particular on the South Atlantic Anomaly -- a feature of the Earth's magnetic field, just over South America, where the magnetic field strength is about 30 percent weaker than in any other region. If incoming electrons were affected by the Earth's magnetic field, Foster reasoned, the South Atlantic Anomaly would act like a "hole in the path of their motion," allowing them to fall deeper into the Earth's atmosphere. Judging from the Van Allen probes' data, however, the electrons kept their distance of 11,000 kilometers, even beyond the effects of the South Atlantic Anomaly -- proof that the Earth's magnetic field had little effect on the barrier.

Foster also considered the effect of long-range, very-low-frequency (VLF) radio transmissions, which others have proposed may cause significant loss of relatively high-energy electrons. Although VLF transmissions can leak into the upper atmosphere, the researchers found that such radio waves would only affect electrons with moderate energy levels, with little or no effect on ultrarelativistic electrons.

Instead, the group found that the natural barrier may be due to a balance between the electrons' slow, earthward motion, and plasmaspheric hiss. This conclusion was based on the Van Allen probes' measurement of electrons' pitch angle -- the degree to which an electron's motion is parallel or perpendicular to the Earth's magnetic field. The researchers found that plasmaspheric hiss acts slowly to rotate electrons' paths, causing them to fall, parallel to a magnetic field line, into Earth's upper atmosphere, where they are likely to collide with neutral atoms and disappear.

Seen through "new eyes"

Foster says this is the first time researchers have been able to characterize the Earth's radiation belt, and the forces that keep it in check, in such detail. In the past, NASA and the U.S. military have launched particle detectors on satellites to measure the effects of the radiation belt: NASA was interested in designing better protection against such damaging radiation; the military, Foster says, had other motivations.

"In the 1960s, the military created artificial radiation belts around the Earth by the detonation of nuclear warheads in space," Foster says. "They monitored the radiation belt changes, which were enormous. And it was realized that, in any kind of nuclear war situation, this could be one thing that could be done to neutralize anyone's spy satellites."

The data collected from such efforts was not nearly as precise as what is measured today by the Van Allen probes, mainly because previous satellites were not designed to fly in such harsh conditions. In contrast, the resilient Van Allen Probes have gathered the most detailed data yet on the behavior and limits of the Earth's radiation belt.

"It's like looking at the phenomenon with new eyes, with a new set of instrumentation, which give us the detail to say, 'Yes, there is this hard, fast boundary,'" Foster says.

INFORMATION:

This research was funded in part by NASA.

Written by Jennifer Chu, MIT News Office

RELATED LINKS

John Foster

MIT Haystack Observatory

ARCHIVE: A river of plasma, guarding against the sun

ARCHIVE: Space weather's effects on satellites

ARCHIVE: Asteroids' close encounters with Mars

CORVALLIS, Ore. - The use of renewable energy in the United States could take a significant leap forward with improved storage technologies or more efforts to "match" different forms of alternative energy systems that provide an overall more steady flow of electricity, researchers say in a new report.

Historically, a major drawback to the use and cost-effectiveness of alternative energy systems has been that they are too variable - if the wind doesn't blow or the sun doesn't shine, a completely different energy system has to be available to pick up the slack. This lack ...

Two donuts of seething radiation that surround Earth, called the Van Allen radiation belts, have been found to contain a nearly impenetrable barrier that prevents the fastest, most energetic electrons from reaching Earth.

The Van Allen belts are a collection of charged particles, gathered in place by Earth's magnetic field. They can wax and wane in response to incoming energy from the sun, sometimes swelling up enough to expose satellites in low-Earth orbit to damaging radiation. The discovery of the drain that acts as a barrier within the belts was made using NASA's ...

PROVIDENCE, R.I. [Brown University] -- A new study led by Brown University reports that older learners retained the mental flexibility needed to learn a visual perception task but were not as good as younger people at filtering out irrelevant information.

The findings undermine the conventional wisdom that the brains of older people lack flexibility, or "plasticity," but highlight a different reason why learning may become more difficult as people age: They learn more than they need to. Researchers call this the "plasticity and stability dilemma." The new study suggests ...

VIDEO:

When people hear another person talking to them, they respond not only to what is being said -- those consonants and vowels strung together into words and sentences --but also...

Click here for more information.

When people hear another person talking to them, they respond not only to what is being said--those consonants and vowels strung together into words and sentences--but also to other features of that speech--the emotional tone and the speaker's gender, for instance. ...

Older people can actually take in and learn from visual information more readily than younger people do, according to new evidence reported in the Cell Press journal Current Biology on November 26. This surprising discovery is explained by an apparent decline with age in the ability to filter out irrelevant information.

"It is quite counterintuitive that there is a case in which older individuals learn more than younger individuals," says Takeo Watanabe of Brown University.

Older individuals take in more at the same time as the stability of their visual perceptual ...

Enzymes inside cells that normally repair damaged DNA sometimes wreck it instead, researchers at the Stanford University School of Medicine have found. The insight could lead to a better understanding of the causes of some types of cancer and neurodegenerative disease.

In a paper to be published online Nov. 27 in Molecular Cell, the researchers explain how the recently discovered mechanism of DNA damage occurs when genetic transcripts, composed of RNA, stick to the DNA instead of detaching from it.

Certain enzymes, called endonucleases, are attracted to DNA/RNA hybrids ...

Researchers at the Center for iPS Cell Research and Application (CiRA), Kyoto University, show that induced pluripotent stem (iPS) cells can be used to correct genetic mutations that cause Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD). The research, published in Stem Cell Reports, demonstrates how engineered nucleases, such as TALEN and CRISPR, can be used to edit the genome of iPS cells generated from the skin cells of a DMD patient. The cells were then differentiated into skeletal muscles, in which the mutation responsible for DMD had disappeared.

DMD is a severe muscular degenerative ...

Mutations in the KRAS gene have long been known to cause cancer, and about one third of solid tumors have KRAS mutations or mutations in the KRAS pathway. KRAS promotes cancer formation not only by driving cell growth and division, but also by turning off protective tumor suppressor genes, which normally limit uncontrolled cell growth and cause damaged cells to self-destruct.

A new University of Iowa study provided a deeper understanding of how KRAS turns off tumor suppressor genes and identifies a key enzyme in the process. The findings, published online Nov. 26 in the ...

SALT LAKE CITY--Researchers from Huntsman Cancer Institute (HCI) at the University of Utah (U of U) discovered the unusual role of lactate in the metabolism of alveolar soft part sarcoma (ASPS), a rare, aggressive cancer that primarily affects adolescents and young adults. The study also confirmed that a fusion gene is the cancer-causing agent in this disease. The research results were published online in the journal Cancer Cell Nov. 26, 2014.

ASPS tumor cells contain a chromosomal translocation--strands of DNA from two chromosomes trade places. The two strands fuse ...

MINNEAPOLIS / ST. PAUL (11/26/2014)--During a thunderstorm, we all know that it is common to hear thunder after we see the lightning. That's because sound travels much slower (768 miles per hour) than light (670,000,000 miles per hour).

Now, University of Minnesota engineering researchers have developed a chip on which both sound wave and light wave are generated and confined together so that the sound can very efficiently control the light. The novel device platform could improve wireless communications systems using optical fibers and ultimately be used for computation ...