(Press-News.org) In the city that never sleeps, it's easy to overlook the insects underfoot. But that doesn't mean they're not working hard. A new study from North Carolina State University shows that insects and other arthropods play a significant role in disposing of garbage on the streets of Manhattan.

"We calculate that the arthropods on medians down the Broadway/West St. corridor alone could consume more than 2,100 pounds of discarded junk food, the equivalent of 60,000 hot dogs, every year - assuming they take a break in the winter," says Dr. Elsa Youngsteadt, a research associate at NC State and lead author of a paper on the work.

"This isn't just a silly fact," Youngsteadt explains. "This highlights a very real service that these arthropods provide. They effectively dispose of our trash for us."

The researchers were in the midst of a long-term study of urban insects when Hurricane Sandy struck NYC in 2012. In spring 2013, they expanded their study to look at whether Sandy had affected the behavior of these insect populations.

The research team sampled arthropods - such as insects and millipedes - in street medians and parks in Manhattan to measure the biodiversity at those sites. The researchers also wanted to see how much garbage those arthropods consumed and whether they consumed more in some places than in others. One hypothesis was that in areas with more biodiversity, insects would consume more garbage.

To see how much the arthropods ate, the researchers put out carefully measured amounts of junk food - potato chips, cookies and hot dogs - at sites in street medians and city parks. Researchers placed two sets of food at each site. One set was placed in a cage, so only arthropods could reach the food; the second set was placed in the open, where other animals could also eat it. After 24 hours, the scientists collected the food to see how much was eaten.

The researchers found that Hurricane Sandy had no measurable impact on food consumption by arthropod populations in New York, which was somewhat surprising since many of the study sites had been flooded with brackish water.

The bigger surprise was that arthropod populations in medians ate two to three times more junk food than those in parks - even though there was less biodiversity in the medians.

"We think this is because one of the most common species in the medians was the pavement ant (Tetramorium species), which is a particularly efficient forager in urban environments," Youngsteadt says.

In addition, by comparing food consumption inside and outside of the sample cages, the researchers showed that other animals - such as rats and pigeons - were also eating the junk food.

"This means that ants and rats are competing to eat human garbage, and whatever the ants eat isn't available for the rats," Youngsteadt explains. "The ants aren't just helping to clean up our cities, but to limit populations of rats and other pests."

INFORMATION:

The paper, "Habitat and species identity, not diversity, predict the extent of refuse consumption by urban arthropods," was published online Dec. 2 in the journal Global Change Biology. The paper was co-authored by former NC State undergraduate Ryanna Henderson; Dr. Amy Savage, a postdoctoral researcher at NC State; Andrew Ernst, a research assistant at NC State; Dr. Rob Dunn, an associate professor of biological sciences at NC State; and Dr. Steven Frank, an associate professor of entomology at NC State.

The work was supported by NSF RAPID grant number 1318655 and by the Department of the Interior's Southeast Climate Science Center, under cooperative agreement numbers G11AC20471 and G13AC00405. The center is based at NC State and provides scientific information to help land managers respond effectively to climate change.

ARLINGTON HEIGHTS, Ill. (December 2, 2014) - If you are one of the millions of Americans who experiences a severe allergic reaction to food, latex or an insect sting, you should know the first line of defense in combating the reaction is epinephrine. Unfortunately, not all medical personnel know how important epinephrine is in bringing an allergic reaction under control.

According to new guidelines published in the Annals of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology, the scientific publication of the American College of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology (ACAAI), the fast administration ...

AUSTIN, Texas -- Researchers at The University of Texas at Austin have identified a network of genes that appear to work together in determining alcohol dependence. The findings, which could lead to future treatments and therapies for alcoholics and possibly help doctors screen for alcoholism, are being published this week in the journal Molecular Psychiatry.

By comparing patterns of genetic code from the brain tissue of alcoholics and nonalcoholics, the researchers discovered a particular set of genes co-expressed together in the individuals who had consumed the most ...

CHICAGO - According to a new long-term study, diabetic patients with even mild coronary artery disease face the same relative risk for a heart attack or other major adverse heart events as diabetics with serious single-vessel obstructive disease. Results of the study were presented today at the annual meeting of the Radiological Society of North America (RSNA).

Researchers at the University of British Columbia and St. Paul's Hospital in Vancouver analyzed data from the Coronary CT Angiography Evaluation For Clinical Outcomes: An International Multicenter (CONFIRM) Registry, ...

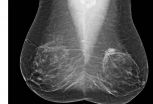

CHICAGO - A major new study being presented at the annual meeting of the Radiological Society of North America (RSNA) has found that digital breast tomosynthesis, also known as 3-D mammography, has the potential to significantly increase the cancer detection rate in mammography screening of women with dense breasts.

Breasts are considered dense if they have a lot of fibrous or glandular tissue but not much fatty tissue. Research has shown that dense breasts are more likely to develop cancer, a problem compounded by the fact that cancer in dense breasts can be difficult ...

CHICAGO - A study of breast cancers detected with screening mammography found that strong family history and dense breast tissue were commonly absent in women between the ages of 40 and 49 diagnosed with breast cancer. Results of the study were presented today at the annual meeting of the Radiological Society of North America (RSNA).

"Screening recommendations for this age group continue to be debated," said Bonnie N. Joe, M.D., Ph.D., associate professor in residence and chief of women's imaging at University of California, San Francisco (UCSF). "Recent publications ...

CHICAGO - Patients value direct, independent access to their medical exams, according to a new study presented at the annual meeting of the Radiological Society of North America (RSNA).

Fragmentation of health information among physicians, healthcare institutions or practices, and inefficient exchange of test results can decrease quality of care and contribute to high medical costs. Improving communications and giving patients more control over their care are critical goals of health IT initiatives.

"Easy and timely electronic access to an online unified source of ...

Disparities in mental-health treatment are known to be associated with patients' racial and ethnic backgrounds. Now, a large study by researchers with UC Davis has found one possible reason for those disparities: Some racial and ethnic minorities are less likely to be assessed and referred for treatment by their medical providers.

The study of more than 9,000 diverse individuals, including Latinos, African-Americans, Asian-Americans and non-Hispanic whites, found that patients of different racial and ethnic backgrounds reported experiencing differing treatment approaches ...

ANN ARBOR, Mich. -- Patients with head and neck cancer who used antacid medicines to control acid reflux had better overall survival, according to a new study from the University of Michigan Comprehensive Cancer Center.

Reflux can be a common side effect of chemotherapy or radiation treatment for head and neck cancer. Doctors at the University of Michigan frequently prescribe two types of antacids - proton pump inhibitors or histamine 2 blockers - to help treat this side effect.

The researchers looked at 596 patients who were treated for head and neck cancer. More than ...

Sons whose fathers have criminal records tend to have lower cognitive abilities than sons whose fathers have no criminal history, data from over 1 million Swedish men show. The research, conducted by scientists in Sweden and Finland, indicates that the link is not directly caused by fathers' behavior but is instead explained by genetic factors that are shared by father and son.

The study is published in Psychological Science, a journal of the Association for Psychological Science.

"The findings are important because cognitive ability is among the most important psychological ...

EVANSTON, Ill. --- Birth weight makes a difference to a child's future academic performance, according to new Northwestern University research that found heavier newborns do better in elementary and middle school than infants with lower birth weights.

Led by a multidisciplinary team of Northwestern researchers, the study raises an intriguing question: Does a fetus benefit from a longer stay in the mother's womb?

"A child who is born healthy doesn't necessarily have a fully formed brain," said David Figlio, one of the study's authors and director of Northwestern's Institute ...