(Press-News.org) CHAPEL HILL, NC - UNC School of Medicine researchers have found for the first time a biochemical mechanism that could be a cause of "chemo brain" - the neurological side effects such as memory loss, confusion, difficulty thinking, and trouble concentrating that many cancer patients experience while on chemotherapy to treat tumors in other parts of the body.

The research, published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, shows how the common chemotherapy drug topotecan can drastically suppress the expression of Topoisomerase-1, a gene that triggers the creation of proteins essential for normal brain function. Specifically, the drug tamps down the proteins that are necessary for neurons to communicate through synapses. However, the researchers found that the protein levels and synaptic communication return to normal when the drug is removed.

"There's still a question in the cancer field about the degree to which some chemotherapies get into the brain," said Mark Zylka, PhD, associate professor of cell biology and physiology and co-senior author of the PNAS paper. "But in our experiments, we show that if they do get in, they can have a dramatic effect on synaptic function. We think drug developers should be aware of this when testing their next generation of topoisomerase inhibitors."

The researchers also suggest that if these synaptic enzymes are affected during brain development and throughout life, then the result could be long-term neurodevelopmental problems, such as those found in people with Autism Spectrum Disorder. Essentially, the brain would be wired incorrectly. Topotecan is not the only "environmental factor" that can suppress the genes linked to autism. Research to quantify these biochemical effects in animals is ongoing at UNC.

The PNAS study comes one year after Zylka and UNC colleague Ben Philpot, PhD, professor of cell biology and physiology, reported in Nature that topotecan halted the expression of unusually long genes in neurons - the same synaptic genes linked to autism. This discovery led them to investigate how topotecan affects the specific topoisomerase enzymes in cancer cells and in neurons.

In the PNAS paper, the researchers describe how topotecan hits its intended target - the topoisomerase proteins that are integral for cell division, a hallmark of cancer cells. But these proteins exist to varying degrees in many cell types.

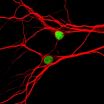

UNC postdoctoral fellow Angela Mabb, PhD, used several biochemical, electrophysiological, and imaging techniques to study how cortical neurons of mice react to topotecan. She found that the drug depleted the synaptic proteins that extremely long genes encode - proteins including Neurexin-1, Neuroligin-1, Cntnap2, and GABAAβ3. This depletion drastically dampened the spontaneous synaptic activity and transmission of signals between neurons. But the main bodies of the neurons remained unaffected.

"The cells seemed quiet, as if in a dormant state," Mabb said. "But they remained healthy. And once the drug was washed out, the synaptic function returned to normal."

Philpot added, "Although we stress that our experiments are with cells in a dish, our results are consistent with the kinds of side effects that cancer patients report during chemotherapy."

These experiments used only topotecan, but there's an entire class of topoisomerase inhibitors. Many other similar drugs are now in development and scientists have already found that these drugs can effectively penetrate the blood-brain barrier.

"Many in the cancer field are focused, as they should be, on whether a drug can kill a tumor, not what the cognitive side effects might be," Zylka said. "But this study provides insights into potential serious side effects of drugs used to treat various forms of cancer. It is very good to know that at UNC we have a big effort to study patient-reported outcomes during therapy so that we can balance care for the whole person."

INFORMATION:

This research was funded by the National Institutes of Health, the Simons Foundation, and the Angelman Syndrome Foundation.

Mark Zylka, PhD, and Ben Philpot, PhD, are both members of the UNC Lineberger Comprehensive Cancer Center, the UNC Neuroscience Center, and the Carolina Institute for Developmental Disabilities.

Coffee, apple juice, and vitamin C: things that people ingest every day are experimental material for chemist Eva-Maria Felix. The doctoral student in the research group of Professor Wolfgang Ensinger in the Department of Material Analysis is working on making nanotubes of gold. She precipitates the precious metal from an aqueous solution onto a pretreated film with many tiny channels. The metal on the walls of the channels adopts the shape of nanotubes; the film is then dissolved. The technique itself is not new, but Felix has modified it: "The chemicals that are usually ...

WASHINGTON, D.C., December 3, 2014--A new report from the American Institute of Physics (AIP) Statistical Research Center has found that the number of Hispanic students receiving bachelor's degrees in the physical sciences and engineering has increased over the last decade or so, passing 10,000 degrees per year for the first time in 2012. The overall number of U.S. students receiving degrees in those fields also increased over the same time, but it increased faster among Hispanics.

From 2002 to 2012, the number of Hispanics earning bachelor's degrees in the physical sciences ...

TALLAHASSEE, Fla. -- A team led by Florida State University researchers has identified DNA elements in maize that could affect the expression of hundreds or thousands of genes.

"Maybe they are part of the machinery that allows an organism to turn hundreds of genes off or on," said Associate Professor of Biological Science Hank Bass.

Bass and Carson Andorf, a doctoral student in computer science at Iowa State University, began this exploration of the maize genome sequence along with colleagues from FSU, Iowa State and the University of Florida. They wanted to know ...

New York, NY, December 2, 2014 - Immediate breast reconstruction following mastectomy is becoming more prevalent. However, in breast cancer patients undergoing simultaneous chemotherapy, thrombotic complications can arise that can delay or significantly modify reconstructive plans. Outcomes of cases illustrating potential complications are published in the current issue of Annals of Medicine and Surgery.

Chemotherapy is increasingly used to treat larger operable or advanced breast cancer prior to surgery. Chemotherapy delivered via the placement of a central venous line ...

Hamilton, ON (Dec. 3, 2014) - Scientists at McMaster University have discovered that human stem cells made from adult donor cells "remember" where they came from and that's what they prefer to become again.

This means the type of cell obtained from an individual patient to make pluripotent stem cells, determines what can be best done with them. For example, to repair the lung of a patient with lung disease, it is best to start off with a lung cell to make the therapeutic stem cells to treat the disease, or a breast cell for the regeneration of tissue for breast cancer ...

CAMBRIDGE, MA -- MIT biological engineers have created a new computer model that allows them to design the most complex three-dimensional DNA shapes ever produced, including rings, bowls, and geometric structures such as icosahedrons that resemble viral particles.

This design program could allow researchers to build DNA scaffolds to anchor arrays of proteins and light-sensitive molecules called chromophores that mimic the photosynthetic proteins found in plant cells, or to create new delivery vehicles for drugs or RNA therapies, says Mark Bathe, an associate professor ...

Vienna, Austria - 3 December 2014: The Mediterranean diet is linked to improved cardiovascular performance in patients with erectile dysfunction, according to research presented at EuroEcho-Imaging 2014 by Dr Athanasios Angelis from Greece. Patients with erectile dysfunction who had poor adherence to the Mediterranean diet had more vascular and cardiac damage.

EuroEcho-Imaging is the annual meeting of the European Association of Cardiovascular Imaging (EACVI), a branch of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC), and is held 3-6 December in Vienna, Austria.

Dr Angelis ...

CHICAGO - Researchers reported today on a procedure that can preserve fertility and potentially save the lives of women with a serious pregnancy complication called placenta accreta. Results of the new study presented at the annual meeting of the Radiological Society of North America (RSNA) showed that placement of balloons in the main artery of the mother's pelvis prior to a Caesarean section protects against hemorrhage and is safe for both mother and baby.

Placenta accreta, a condition in which the placenta abnormally implants in the uterus, can lead to additional complications, ...

CHICAGO - Researchers at Mayo Clinic found that some children are receiving chest X-rays that may be unnecessary and offer no clinical benefit to the patient, according to a study presented today at the annual meeting of the Radiological Society of North America (RSNA).

"Chest X-rays can be a valuable exam when ordered for the correct indications," said Ann Packard, M.D., radiologist at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn. "However, there are several indications where pediatric chest X-rays offer no benefit and likely should not be performed to decrease radiation dose ...

CHICAGO - A popular surgery to repair meniscal tears may increase the risk of osteoarthritis and cartilage loss in some patients, according to research presented today at the annual meeting of the Radiological Society of North America (RSNA). The findings show that the decision for surgery requires careful consideration in order to avoid accelerated disease onset, researchers said.

The new study focused on the meniscus, a wedge-shaped piece of cartilage in the knee that acts as a shock absorber between the femur, or thighbone, and tibia, or shinbone. The two menisci ...