(Press-News.org) PITTSBURGH, Dec. 3, 2014 - Sophisticated lung imaging can show whether or not a treatment drug is able to clear tuberculosis (TB) lung infection in human and macaque studies, according to researchers at the University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine and their international collaborators.

The findings, published online today in Science Translational Medicine, indicate the animal model can correctly predict which experimental agents have the best chance for success in human trials.

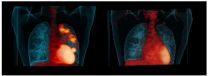

The image on the left shows "hot spots" of infection in a patient's lungs before treatment. The image on the right shows the disease improvement after six months of taking the drug linezolid.

In 2012, an estimated 8.6 million people in the world contracted TB, for which the first-line treatment demands taking four different drugs for six to eight months to get a durable cure, explained senior investigator JoAnne L. Flynn, Ph.D., professor of microbiology and molecular genetics, Pitt School of Medicine. Patients who aren't cured of the infection - about 500,000 annually - can develop multi-drug resistant TB, and have to take as many as six drugs for two years.

"Some of those people don't get cured, either, and develop what we call extensively drug-resistant, or XDR, TB, which has a very poor prognosis," she said.

"Our challenge is to find more effective treatments that work in a shorter time period, but the standard preclinical models for testing new drugs have occasionally led to contradictory results when they are evaluated in human trials."

In previous research, Dr. Flynn's colleagues at the National Institutes of Health found that the drug linezolid effectively treated XDR-TB patients who had not improved with conventional treatment, even though mouse studies suggested it would have no impact on the disease.

To further examine the effects of linezolid and another drug of the same class, Dr. Flynn and her NIH collaborators, led by Clifton E. Barry III, PH.D., performed PET/CT scans in TB-infected humans and macaques, which also get lesions known as granulomas in the lungs. In a PET scan, a tiny amount of a radioactive probe is injected into the blood that gets picked up by metabolically active cells, leaving a "hot spot" on the image.

The researchers found that humans and macaques had very similar disease profiles, and that both groups had hot spots of TB in the lungs that in most cases improved after drug treatment. CT scans, which show anatomical detail of the lungs, also indicated post-treatment improvement. One patient had a hot spot that got worse, and further testing revealed his TB strain was resistant to linezolid.

The findings show that a macaque model and PET scanning can better predict which drugs are likely to be effective in clinical trials, and that could help get new treatments to patients faster, Dr. Flynn said. The scans also could be useful as a way of confirming drug resistance, but aren't likely to be implemented routinely.

"We plan to use this PET scanning strategy to determine why some lesions don't respond to certain drugs, and to test candidate anti-TB agents," she said. "This might give us a way of tailoring treatment to individuals."

INFORMATION:

The research team includes lead author M. Teresa Coleman and others from the Pitt School of Medicine and Children's Hospital of Pittsburgh of UPMC; co-senior author Dr. Barry and others from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, part of the National Institutes of Health; as well as scientists from the International Tuberculosis Research Center in Changwon, Republic of Korea; Rutgers New Jersey Medical School; Frederick National Laboratory for Cancer Research; Yonsei University College of Medicine, Seoul, Republic of Korea; and the University of Cape Town, Rondebosch, South Africa.

Funding for this study was provided by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases and the National Cancer Institute; the Ministry of Health and Welfare, Republic of Korea; and the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation.

About the University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine

As one of the nation's leading academic centers for biomedical research, the University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine integrates advanced technology with basic science across a broad range of disciplines in a continuous quest to harness the power of new knowledge and improve the human condition. Driven mainly by the School of Medicine and its affiliates, Pitt has ranked among the top 10 recipients of funding from the National Institutes of Health since 1998. In rankings recently released by the National Science Foundation, Pitt ranked fifth among all American universities in total federal science and engineering research and development support.

Likewise, the School of Medicine is equally committed to advancing the quality and strength of its medical and graduate education programs, for which it is recognized as an innovative leader, and to training highly skilled, compassionate clinicians and creative scientists well-equipped to engage in world-class research. The School of Medicine is the academic partner of UPMC, which has collaborated with the University to raise the standard of medical excellence in Pittsburgh and to position health care as a driving force behind the region's economy. For more information about the School of Medicine, see http://www.medschool.pitt.edu.

Scientists from WCS (Wildlife Conservation Society), the American Museum of Natural History (AMNH), the Environment Society of Oman, and other organizations have made a fascinating discovery in the northern Indian Ocean: humpback whales inhabiting the Arabian Sea are the most genetically distinct humpback whales in the world and may be the most isolated whale population on earth. The results suggest they have remained separate from other humpback whale populations for perhaps 70,000 years, extremely unusual in a species famed for long distance migrations.

The study appears ...

PULLMAN, Wash. - Sitting on an exam table in a flimsy gown can intimidate anyone. If you also happen to be lesbian, gay or bisexual, the experience can be even worse.

As a woman of sexual minority, Nicole Flemmer has encountered medical misinformation and false assumptions. She was once diagnosed with "ego dystonic homosexuality" - a long-discredited term - without her knowledge or an appropriate discussion with the doctor. She discovered the notation years later when she happened to glance at her medical chart.

Such experiences left her hesitant to access health ...

WEST LAFAYETTE, Ind. - A neurotoxin called acrolein found in tobacco smoke that is thought to increase pain in people with spinal cord injury has now been shown to accumulate in mice exposed to the equivalent of 12 cigarettes daily over a short time period.

One implication is that if acrolein is exacerbating pain its concentration in the body could be reduced using the drug hydralazine, which has been approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for hypertension, said Riyi Shi (pronounced Ree Shee), a professor in Purdue University's Department of Basic Medical Sciences, ...

DURHAM, N.C. -- Citizens who get involved in science become more environmentally aware and willing to participate in advocacy than previously thought, according to a new study by researchers at Duke University's Nicholas School of the Environment. Citizen science projects can lead to broader public support for conservation efforts.

The study, led by PhD student McKenzie Johnson, appeared in November in the journal Global Environmental Change. It surveyed 115 people who had recently participated in citizen science projects in India with the Wildlife Conservation Society ...

An enzyme that usually triggers strong allergic reactions now circulates in the veins of a group of mice without alerting the immune system. As INRS Énergie Matériaux Télécommunications Research Centre Professor Marc A. Gauthier explains in an article published in the journal Nature Communications, a polymer was used to camouflage the enzyme before it was injected into the rodents. This was achieved by coating the enzyme to avoid an immune response in a manner that does not compromise its activity. The first in vivo demonstration has opened the door ...

DURHAM, N.C. -- Scientists have developed a way to sniff out tiny amounts of toxic gases -- a whiff of nerve gas, for example, or a hint of a chemical spill -- from up to one kilometer away.

The new technology can discriminate one type of gas from another with greater specificity than most remote sensors -- even in complex mixtures of similar chemicals -- and under normal atmospheric pressure, something that wasn't thought possible before.

The researchers say the technique could be used to test for radioactive byproducts from nuclear accidents or arms control treaty ...

Alcohol use is a major risk factor for head and neck cancer. But an article published in the November issue of the journal Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology shows that the chemical resveratrol found in grape skins and in red wine may prevent cancer as well.

"Alcohol bombards your genes. Your body has ways to repair this damage, but with enough alcohol eventually some damage isn't fixed. That's why excessive alcohol use is a factor in head and neck cancer. Now, resveratrol challenges these cells - the ones with unrepaired DNA damage are killed, so they can't ...

West Orange, NJ. December 3, 2014. Brain injury researchers in New Jersey have identified retrieval practice as a useful strategy for improving memory among children and adolescents with traumatic brain injury (TBI). "Retrieval Practice as an Effective Memory Strategy in Children and Adolescents with TBI" (DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.apmr.2014.09.022) was published online ahead of print on October 10 by the Archives of Physical Medicine & Rehabilitation. This article is based on a collaborative study funded by Kessler Foundation and Children's Specialized Hospital. ...

As the two foolish pigs learned before running to their brother's solidly built house of bricks for safety, when the wolf comes calling, the quality of your shelter is everything.

Animals in the wild have always instinctively known this. But changes to their habitat in the wake of human encroachment, climate change and a variety of environmental influences are affecting the predator-prey relationship and creating new "fearscapes" dotted with predation risks.

To better understand what's happening, researchers are using innovative imaging techniques to map the properties ...

DETROIT - A common prostate cancer therapy should not be used in men whose cancer has not spread beyond the prostate, according to a new study led by researchers at Henry Ford Hospital.

The findings are particularly important for men with longer life expectancies because the therapy exposes them to more adverse side effects, and it is associated with increased risk of death and deprives men of the opportunity for a cure by other methods.

The research study has been published online in European Urology.

The focus of the new study is androgen deprivation therapy (ADT), ...