But a new technique to transmute living cells into more permanent materials that defy rot and can endure high-powered probes is widening research opportunities for biologists who are developing cancer treatments, tracking stem cell evolution or even trying to understand how spiders vary the quality of the silk they spin. The simple, silica-based method also offers materials scientists the ability to "fix" small biological entities like red blood cells into more commercially useful shapes. And, at least in theory, the method can transmute naturally grown objects like livers and spleens from livestock into non-organic "zombie" replicas that function simultaneously at a variety of length-scales, from macro to nano, in more sophisticated ways than the most advanced machinery can produce.

"Why go to the trouble of making objects if nature will do it for you?" asks lead investigator Bryan Kaehr, of the Department of Energy's Sandia National Laboratories.

The unusual method has been the subject of papers in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, the Journal of the American Chemical Society (JACS), and on Dec. 8, Nature Communications.

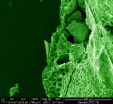

The initial insight came when Kaehr and then-University of New Mexico (UNM) postdoctoral student Jason Townson discovered that the silica slurry they were using had an unexpected property: At a reasonably low pH level, the silica molecules, instead of clotting with each other, bound only to surfaces against which they rested, forming the thinnest of coatings. Kaehr wondered if a similar coating on biological cells would strengthen cell structures so they could be examined for longer periods with more powerful tools. So the researchers put cultured tissue cells in a silica solution and let the mix harden overnight. Then they raised the temperature to burn off the biomaterial. What remained, astonishingly, were perfectly replicated cells, like little row houses of glass.

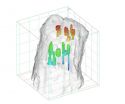

But the replicated cells were so sturdy that Kaehr surmised that the slurry must have coated the cells inside as well as out. Breaking a row of cells as one would a tiny pane of glass, the team examined their interiors with an electron microscope. They found they had indeed replicated the nanoscopic organelles of the cell as well as its exterior. They had discovered a way to create a near-perfect silica counterfeit of a biological organism, from its overall shape down to its nanostructures. This initial result is already being used by biologists in Finland to create three-dimensional models that preserve the different stages of stem cells as they evolve to their final form, said Sandia fellow and paper co-author Jeff Brinker, who is also a UNM professor. Townson, now on the faculty at UNM, uses the method to research the movements of cancer-fighting nanoparticles inserted into chicken cells prior to their conversion to silica. "With optical microscopy, it is difficult to form an image of the interactions of nanoparticles with cells while preserving a three-dimensional context," he said. Bioreplication, where the sample can be mechanically dissected and investigated with electron microscopes, offers better 3-D resolution at the nanoscale. The method also is being used in England's Oxford University to study the internal biological changes by which spiders create different types of silk, adjusting their mechanisms on the fly (so to speak) to create thicker or stickier strands, said Brinker. Blood as a possible raw material

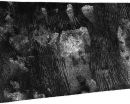

In the JACS article, Kaehr and colleagues showed they could use the silica technique to make permanent alterations in natural objects. They introduced chemicals that transformed red blood cells from life-saver-like objects to spiky spheres. By introducing the silica slurry to the dish containing the altered red blood cells and letting the mixture harden, Kaehr and colleagues made the change permanent. Burning off the protoplasmic original, the team was left with microparticles that might be useful in rubber composites created by tire companies that routinely insert silica spheres in their tire mix for additional strength. Manufacturers would no longer need an energy-consuming factory to make the inserted material which, by bioreplication, would form cheaply and easily, Kaehr said. Said Kaehr. "Our method has good potential over traditional silica additives, and its raw material -- blood -- is considered a waste product in the meat industry. " In addition to food industry waste products, he said, "there's a huge amount of harmless bacteria out there we could co-opt to create still other shapes." Bacteria are harder to harvest, he said, because they are protected by a double sheath against silica invasion, but it could be done. In the Nature Communications paper, Kaehr and colleagues took the same technique a step further. They took a liver, submerged it in a silica solution and then heated it anaerobically to come up with a hardened, carbonized, exact duplicate of the liver, from centimeter to nanometer scales. "We let nature do the work," he said, "because we don't yet know how to build an object accurately across six length scales, from centimeter to nanometers.

"Think about electrodes in batteries," he said. "That's a three-dimensional question. Now in livers and spleens, for example, evolution has already optimized absorption and diffusion in a three-dimensional organization. The liver is a marvelously effective organ with tremendous surface area for absorption and an unparalleled ability to release materials in channels ranging from large arteries to capillaries a few micrometers wide. "If we transfer the hierarchical structure of a liver to an electrode, rather than having just a passive piece of solid material, we would have greater surface area per volume, greater energy storage, and have a creation that is already optimized to output fluids and small particles to much larger highways like large veins and arteries." The carbonized method also can be used to better examine cancers and other growths without the often tedious and expensive processes normally necessary to "fix," process and stabilize the organic material for examination to prevent it from falling apart under electron-beam analysis. Carbon, because it conducts electricity instead of absorbing it, is not weakened and destroyed like protoplasm. This creative consideration of the possibilities of the natural world in new and dizzying ways is in line with Kaehr's research sponsor --DOE's Office of Science, which is interested in "the exploration, discovery and design of biomimetic materials," he said. Portions of this work were performed at the Center for Integrated Nanotechnologies, a DOE Office of Science User Facility jointly led by Los Alamos and Sandia National Laboratories.

INFORMATION:

Sandia and UNM have applied for a joint patent on the set of methods.

Sandia National Laboratories is a multi-program laboratory operated by Sandia Corporation, a wholly owned subsidiary of Lockheed Martin Corp., for the U.S. Department of Energy's National Nuclear Security Administration. With main facilities in Albuquerque, N.M., and Livermore, Calif., Sandia has major R&D responsibilities in national security, energy and environmental technologies and economic competitiveness.