(Press-News.org) A leopard may not be able to change its spots, but new research from a World Heritage site in Nepal indicates that leopards do change their activity patterns in response to tigers and humans--but in different ways.

The study is the first of its kind to look at how leopards respond to the presence of both tigers and humansLeopard in Chitwan, Nepal simultaneously. Its findings suggest that leopards in and around Nepal's Chitwan National Park avoid tigers by seeking out different locations to live and hunt. Since tigers--the socially dominant feline--prefer areas less disturbed by people, leopards are displaced closer to humans. Though they may share some of the same spaces, leopards avoid people on foot and vehicles by shifting their activity to the night.

A scientific paper based on the study, led by Neil Carter, postdoctoral fellow at the National Socio-Environmental Synthesis Center (SESYNC), was published this week in the journal Global Ecology and Conservation. In addition to Carter, the co-authors are Micah Jasny of Duke University, Bhim Gurung of the Nepal Tiger Trust in Chitwan, and Jianguo "Jack" Liu of Michigan State University.

"This study shows the complexity of coupled human and natural systems," said Liu, director of the Michigan State University Center for Systems Integration and Sustainability. "It also demonstrates the challenge of conserving multiple endangered species simultaneously."

Most areas where leopards and tigers co-exist are human-dominated. Accounting for the multi-layered interactions between leopards, tigers, and people is therefore key to understanding the ripple effects of human activities such as conservation actions, the researchers say.

The study has important implications in light of the Global Tiger Recovery Program, which is committed to doubling the worldwide tiger population by 2022. As tiger populations--and the territories they occupy--grow, leopards are increasingly likely to be pushed into areas where people live. The jostling of wildlife occupancy may open the door to more conflicts between people and leopards that could include leopard attacks on both people and livestock, as well as retaliatory killings of leopards.

The researchers' findings underscore how successful conservation efforts need science that takes into account the complex feedbacks between humans and nature.

"We want to see increased tiger numbers--that's a great outcome from a conservation perspective. But we also need to anticipate reverberations throughout other parts of the coupled human and natural systems in which tigers are moving into," said Carter, "such as the ways leopards respond to their new cohabitants, and in turn how humans respond to their new cohabitants."

While working on his doctoral degree at Michigan State, Carter spent two seasons setting motion-detecting camera traps for leopards, tigers, their prey, and the people who walk the roads and trails of Chitwan, both in and around the park. Chitwan, nestled in a valley along the lowlands of the Himalayas, is home to high numbers of leopards and tigers. People live on the park's borders, but rely on the forests for ecosystem services such as wood and grasses. They venture in on dirt roads and narrow footpaths to be 'snared' on Carter's digital memory cards. The roads also are used by military patrols to thwart would-be poachers.

Analyses of the thousands of camera trap images begin to tell the story of who is using which spaces and when they're using them. Sometimes, though, 'seeing' isn't enough.

"People who use camera traps and other kinds of related monitoring tools realize there's a possibility that the animal is there, but you just didn't detect it," said Carter. "For example, your area of interest may be too large to set up cameras everywhere. Or, it's harder to detect animals in certain forest types if there are a lot of leafy trees blocking the camera's field of view--even if the animal is right there."

Because traditional field-based research can be logistically restrictive, time-intensive, and expensive, the researchers used cutting-edge computational models to fill in data gaps and statistically estimate the location and timing of leopard-tiger-human activity.

"The computational component of this research is essential since it allows us to make strong inferences about leopard behavior in Chitwan based on a small sample," said Jasny, who spent an internship at CSIS working on the leopard-tiger-human data with Carter.

Carter says that while there are many models that look quantitatively at the relationships amongst ecological components of an ecosystem, those models rarely consider humans. Integrating human activity adds a layer of real-world complexity that is more representative of the ecosystem as a whole--providing insights that can help researchers better understand how people and wildlife mutually influence one another.

INFORMATION:

The research was funded by the United States Fish and Wildlife Service Rhinoceros and Tiger Conservation Fund, National Science Foundation (Partnerships in International Research and Education, Dynamics of Coupled Natural and Human Systems Program), MSU AgBioResearch and National Aeronautics and Space Administration's Earth and Space Science Program.

MAYWOOD, Ill. -- Results of treating shoulder pain in baseball pitchers and other throwing athletes are not as predictable as doctors, patients and coaches would like to think, according to a report in the journal Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation Clinics of North America.

Nickolas Garbis, MD, an orthopedic surgeon who specializes in shoulder and elbow injuries at Loyola University Medical Center, is the primary author.

Shoulder pain occurs in athletes who play sports that require rapid acceleration and deceleration of the throwing arm. They include baseball pitchers, ...

James Ingle, M.D., an internationally recognized breast cancer expert, will receive the 2014 William L. McGuire Memorial Lecture Award on Dec. 10 at the 2014 San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium.

Dr. Ingle is a professor of oncology and the Foust Professor in the Mayo Clinic College of Medicine in Rochester, Minnesota. He has been the leader of breast cancer research at the Mayo Clinic Cancer Center, serving as program co-leader of the women's cancer program with responsibility for breast cancer. He is currently co-director of the Mayo Clinic Breast Cancer Specialized ...

(Boston)-- Moms who use mobile devices while eating with their young children are less likely to have verbal, nonverbal and encouraging interactions with them. The findings, which appear online in Academic Pediatrics, may have important implications about how parents balance attention between their devices with their children during daily life.

Parent-child interactions during meal time in particular show a protective effect on child health outcomes such as obesity, asthma and adolescent risk behaviors. These findings have been attributed to the positive family communication ...

DURHAM, N.C. -- In the battle between native and invasive wetland plants, a new Duke University study finds climate change may tip the scales in favor of the invaders -- but it's going to be more a war of attrition than a frontal assault.

"Changing surface-water temperatures, rainfall patterns and river flows will likely give Japanese knotweed, hydrilla, honeysuckle, privet and other noxious invasive species an edge over less adaptable native species," said Neal E. Flanagan, visiting assistant professor at the Duke Wetland Center, who led the research.

Increased human ...

PULLMAN, Wash. - Imagine standing in a long line at your favorite coffee shop only to receive the wrong order. What would you do?

While some might be angry and tell all their friends about the shop's bad service, researchers say other customers may think "it's all good" - IF they learn that the coffee shop donates a percentage of every purchase to charitable causes that customers value.

Corporate social responsibility maximizes consumer return

Writing in the Journal of Public Policy and Marketing, researchers help firms understand when and why corporate social responsibility ...

SAN FRANCISCO (DECEMBER 9, 2014) -Common variations in four genes related to brain inflammation or cells' response to damage from oxidation may contribute to the problems with memory, learning and other cognitive functions seen in children treated for acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL), according to a study led by researchers from Boston Children's Hospital, The Children's Hospital at Montefiore, and Dana-Farber/Boston Children's Cancer and Blood Disorders Center.

The data, presented at the 56th annual meeting of the American Society of Hematology (abstract #856), suggest ...

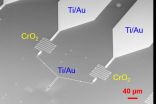

WASHINGTON, D.C., December 9, 2014 - Researchers from the London Centre for Nanotechnology have made new compact, high-value resistors for nanoscale quantum circuits. The resistors could speed the development of quantum devices for computing and fundamental physics research. The researchers describe the thin-film resistors in an article in the Journal of Applied Physics, from AIP Publishing.

One example of an application that requires high-value resistors is the quantum phase-slip (QPS) circuit. A QPS circuit is made from very narrow wires of superconducting material ...

It may be possible to develop a simple blood test that, by detecting changes in the zinc in our bodies, could help to diagnose breast cancer early.

A team, led by Oxford University scientists, took techniques normally used to analyse trace metal isotopes for studying climate change and planetary formation and applied them to how the human body processes metals.

In a world-first the researchers were able to show that changes in the isotopic composition of zinc, which can be detected in a person's breast tissue, could make it possible to identify a 'biomarker' (a measurable ...

December 9, 2014 - Within a few months after drug withdrawal, patients in recovery from dependence on prescription pain medications may show signs that the body's natural reward systems are normalizing, reports a study in the Journal of Addiction Medicine, the official journal of the American Society of Addiction Medicine. The journal is published by Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, a part of Wolters Kluwer Health.

The study by Scott C. Bunce, PhD, of Penn State University College of Medicine, Hershey, and colleagues provides evidence of "physiological re-regulation" ...

Physical aggression in toddlers has been thought to be associated with the frustration caused by language problems, but a recent study by researchers at the University of Montreal shows that this isn't the case. The researchers did find, however, that parental behaviours may influence the development of an association between the two problems during early childhood. Frequent hitting, kicking, and a tendency to bite or push others are examples of physical aggression observed in toddlers.

"Since the 1940s, studies have observed an association between physical aggression ...