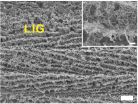

Under a microscope, what the researchers call laser-induced graphene (LIG) doesn't look like a perfect chicken wire-like grid of atoms. Instead, it's a jumble of interconnected graphene flakes with five-, six- and seven-atom rings. The paired five- and seven-atom rings are considered defects - but in this case, they're not. They're features.

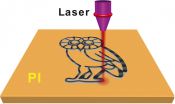

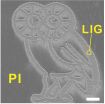

The material can be made in detailed patterns. For show-and-tell, the Rice team patterned millimeter-sized LIG Owls (the school's mascot), and for practical testing they fabricated microscale supercapacitors with LIG electrodes in one-step scribing.

The labs of Rice chemist James Tour and theoretical physicist Boris Yakobson published their research online today in Nature Communications. The one-step process is scalable, said Tour, who suggested it could allow for rapid roll-to-roll manufacture of nanoscale electronics.

"This will be good for items people can relate to: clothing and wearable electronics like smartwatches that configure to your smartphone," he said.

This top-down approach to making graphene is quite different from previous works by Tour's lab, which pioneered the small-scale manufacture of the atom-thick material from common carbon sources, even Girl Scout cookies, and learned to split multiwalled nanotubes into useful graphene nanoribbons.

But as in the previous work, the base material for LIG is inexpensive. "You buy polyimide flexible plastic sheets in huge rolls, called Kapton, and the process is done entirely in air with a rapid writing process. That sets it up for a very scalable, industrial process," Tour said.

The product is not a two-dimensional slice of graphene but a porous foam of interconnected flakes about 20 microns thick. The laser doesn't cut all the way through, so the foam remains attached to a manageable, insulating, flexible plastic base.

The process only works with a particular polymer. The researchers led by Jian Lin, a former postdoctoral research in the Tour Group and now an assistant professor at the University of Missouri, tried 15 different polymers and found only two could be converted to LIG. Of those, polyimide was clearly the best.

Tour said the resulting graphene isn't as conductive as copper, but it doesn't need to be. "It's conductive enough for many applications," he said.

He said LIG can easily be turned into a supercapacitor, which combines the fast-charging, power-storing capacity of a capacitor with the higher energy-delivering capability, though not yet as high as in a battery. The defects could be the key, Tour said.

"A normal sheet of graphene is full of six-member rings," he said. "Once in a while you see a meandering line of 5-7s, but this new material is filled with 5-7s. It's a very unusual structure, and these are the domains that trap electrons. Had it just been normal (highly conductive) graphene, it couldn't store a charge."

Calculations by Yakobson's group showed that these balancing five-and-seven formations make the material more metallic and enhance its ability to store charges.

"Theoretical methods and density functional computations allowed us to look inside the electronic energy states' organization," Yakobson said. "What we discovered is that the very low density of available states -- which is crucial for the layer capacitance -- increases dramatically, due to various topological defects, mainly pentagonal and heptagonal rings.

"The fact that highly defective graphene performs so well is a freebie, a gift from nature," he said.

Miguel José Yacaman, chairman of the Department of Physics at the University of Texas at San Antonio, contributed his expertise in transmission electron microscope imaging to confirm the existence of so many defects.

"We have what is called aberration-corrected microscopy, which allows us to see the defects," Yacaman said. "The resolution is below 1 angstrom, basically 70 picometers (trillionths of a meter), and that's what you need to really look at single atoms."

Tour's lab used the machine shop lasers at Rice's Oshman Engineering Design Kitchen to create their robust microsupercapacitors. The best results showed capacitance of more than 4 millifarads per square centimeter and power density of about 9 milliwatts per square centimeter, comparable to other carbon-based microsupercapacitors, and negligible degradation after as many as 9,000 charge/discharge cycles. This capacitance is sufficient for inexpensive wearable electronic devices, and Tour said his group continues to make improvements. He said the lab didn't start out looking for LIG. "Everything converged. Nature can be a hard taskmaster, but once in a while, she gives you something much better than what you had asked for. Or expected."

INFORMATION:

Co-authors are Rice graduate students Zhiwei Peng, Yuanyue Liu, Ruquan Ye and Errol Samuel; and Francisco Ruiz-Zepeda, a researcher at the University of Texas at San Antonio. Yakobson is Rice's Karl F. Hasselmann Professor of Materials Science and NanoEngineering, a professor of chemistry and a member of the Richard E. Smalley Institute for Nanoscale Science and Technology. Tour is the T.T. and W.F. Chao Chair in Chemistry as well as a professor of materials science and nanoengineering and of computer science.

The Air Force Office of Scientific Research and its Multidisciplinary University Research Initiative (MURI), the Office of Naval Research MURI, the National Center for Research Resources, the National Science Foundation Partnerships for Research and Education in Materials and the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities, part of the National Institutes of Health, supported the research.

Watch a video of LIG microsupercapacitors being created at http://youtu.be/N47UpNONzOk

Read the abstract at http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/ncomms6714

This news release can be found online at http://news.rice.edu/2014/12/10/defects-are-perfect-in-laser-induced-graphene/

Follow Rice News and Media Relations via Twitter @RiceUNews

Related Materials:

Tour Group: http://www.jmtour.com

Yakobson Research Group: http://biygroup.blogs.rice.edu

Wiess School of Natural Sciences: http://naturalsciences.rice.edu

Rice Department of Materials Science and NanoEngineering: http://msne.rice.edu

Images for download:

http://news.rice.edu/wp-content/uploads/2014/12/1215-LIG-1-web.jpg

A Rice University lab is using a laser to write graphene microsupercapacitors in a common polymer material. The laser removes nearly everything but carbon from a 20-micron layer, leaving behind porous graphene foam that may be suitable for electronics or energy storage. (Credit: Tour Group/Rice University)

http://news.rice.edu/wp-content/uploads/2014/12/1215-LIG-2-web.jpg

Graphene microsupercapacitors were created in polymer with a laser at Rice University's Oshman Engineering Design Kitchen. The room-temperature process makes graphene that may be suitable for electronics or energy storage. (Credit: Tour Group/Rice University)

http://news.rice.edu/wp-content/uploads/2014/12/1215-LIG-3-web.jpg

A Rice University lab is using a laser to write graphene microsupercapacitors in a common polymer material. The laser removes nearly everything but carbon from a 20-micron layer, leaving behind porous graphene foam that may be suitable for electronics or energy storage. (Credit: Tour Group/Rice University)

http://news.rice.edu/wp-content/uploads/2014/12/1215-LIG-4-web.jpg

A scanning electron microscope shows a close-up of laser-induced graphene foam produced by researchers at Rice University. The scale bar for the main image is 10 microns; the bar for the inset is 1 micron. (Credit: Tour Group/Rice University)

http://news.rice.edu/wp-content/uploads/2014/12/1215-LIG-5-web.jpg

This finely detailed Rice Owl was produced by burning a graphene foam pattern into a flexible polyimide sheet with a laser. The multilayered graphene that results from the process may be suitable for energy storage or electronics. The scale bar is 1 millimeter. (Credit: Tour Group/Rice University)

Located on a 300-acre forested campus in Houston, Rice University is consistently ranked among the nation's top 20 universities by U.S. News & World Report. Rice has highly respected schools of Architecture, Business, Continuing Studies, Engineering, Humanities, Music, Natural Sciences and Social Sciences and is home to the Baker Institute for Public Policy. With 3,920 undergraduates and 2,567 graduate students, Rice's undergraduate student-to-faculty ratio is just over 6-to-1. Its residential college system builds close-knit communities and lifelong friendships, just one reason why Rice is highly ranked for best quality of life by the Princeton Review and for best value among private universities by Kiplinger's Personal Finance. To read "What they're saying about Rice," go here.