A control knob for fat?

A protein that makes other proteins also regulates fat levels in worms, and may do so in humans

2014-12-12

(Press-News.org) Like a smart sensor that adjusts the lighting in each room and a home's overall temperature, a protein that governs the making of other proteins in the cell also appears capable of controlling fat levels in the body.

The finding, which appeared in Cell Reports on Dec. 11, applies to the Maf1 protein in worms.

A version of the protein, which exists in humans, also regulates protein production in the cell, raising the possibility that it too may control fat storage. A protein with such a function would offer a new target for pharmaceuticals to regulate fat, said Sean Curran, assistant professor at the USC Davis School of Gerontology and the study's corresponding author.

"We've known about Maf1 for over a decade, but so far people have only studied it in single cells, where it is known to regulate protein synthesis," Curran said. "No one really looked at its effect on the whole organism before."

It turns out that Maf1 plays a much more significant role in a whole animal: altering how the animal stores fat.

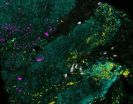

Curran and his colleagues tweaked the amount of Maf1 in C. elegans, a transparent worm often used as a model organism by biologists.

The team found that adding in a single extra copy of gene that expresses Maf1 decreased stored lipids by 34 percent, while reducing Maf1 levels increased stored lipids by 94 percent.

As expected from previous research, increased Maf1 lowered protein synthetic capacity while reduced Maf1 raised it.

Curran collaborated with USC graduate student Akshat Khanna and Deborah Johnson, formerly of the Keck School of Medicine of USC and now dean of the Graduate School of Biomedical Sciences at the Baylor College of Medicine.

"It's really exciting to find a completely new role for such a well-studied molecule," Khanna said.

Johnson published a related paper, released on the same day in PLoS Genetics, showing that Maf1 changes lipid metabolism in cancer cells, raising the possibility that it could be used in tumor cell suppression.

Next, Curran and his colleagues plan to explore whether the results hold true for mice and if so, plan to see whether they also do for humans.

INFORMATION:

The research was supported by the National Institutes of Health (grant numbers GM109028 and AG032308), the American Heart Association (14GRNT20280731), The Ellison Medical Foundation (AG-NS-0748-11) and the American Federation of Aging Research (002666-00001).

The full study can be found online here: http://www.cell.com/cell-reports/abstract/S2211-1247(14)01001-8

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

2014-12-12

The Perioperative Surgical Home (PSH) model consistently and significantly improves quality of care for patients and reduces health care costs, reports a first-of-its-kind, large-scale literature review of the PSH in the United States and abroad. The review, published online this month in Milbank Quarterly, provides further evidence to support the benefits, and encourage the adoption, of the PSH model.

"There is a global push for more rigorously coordinated and integrated management of surgical patients to enhance patient satisfaction and improve quality of care and ...

2014-12-12

Oil reservoirs are scattered deep inside the Earth like far-flung islands in the ocean, so their inhabitants might be expected to be very different, but a new study led by Dartmouth College and University of Oslo researchers shows these underground microbes are social creatures that have exchanged genes for eons.

The study, which was led by researchers at Dartmouth College and the University of Oslo, appears in the ISME Journal. A PDF is available on request.

The findings shed new light on the "deep biosphere," or the vast subterranean realm whose single-celled residents ...

2014-12-12

BOZEMAN, Mont. - Cathy Cripps doesn't seem to worry about the grizzly bears and black bears that watch her work, but she is concerned about the ghosts and skeletons she encounters.

The ghosts are whitebark pine forests that have been devastated by mountain pine beetles and white pine blister rust, said the Montana State University scientist who studies fungi that grow in extreme environments. The skeletons are dead trees that no longer shade snow or produce pine cones. The round purple pine cones hold the seeds that feed bears, red squirrels and Clark's nutcracker birds. ...

2014-12-12

Amsterdam, NL, December 12, 2014 - A patient who had suffered a traumatic brain injury unexpectedly recovered full consciousness after the administration of midazolam, a mild depressant drug of the GABA A agonists family. This resulted in the first recorded case of an "awakening" from a minimally-conscious state (MCS) using this therapy. Although similar awakenings have been reported using other drugs, this dramatic result was unanticipated. It is reported in Restorative Neurology and Neuroscience.

Traumatic brain injuries occur at high rates all over the world, estimated ...

2014-12-12

New Rochelle, NY, December 11, 2014--In cases of traumatic brain injury (TBI), predicting the likelihood of a cranial lesion and determining the need for head computed tomography (CT) can be aided by measuring markers of bone injury in the blood. The results of a new study comparing the usefulness of two biomarkers released into the blood following a TBI are presented in Journal of Neurotrauma, a peer-reviewed journal from Mary Ann Liebert, Inc., publishers. The article is available free on the Journal of Neurotrauma website at http://online.liebertpub.com/doi/full/10.1089/neu.2013.3245 ...

2014-12-12

Training older people in the use of social media improves cognitive capacity, increases a sense of self-competence and could have a beneficial overall impact on mental health and well-being, according to a landmark study carried out in the UK.

A two-year project funded by the European Union and led by the University of Exeter in partnership with Somerset Care Ltd and Torbay & Southern Devon Health and Care NHS Trust gave a group of vulnerable older adults a specially-designed computer, broadband connection and training in how to use them.

Those who received training ...

2014-12-12

WOODS HOLE, Mass.--Since the first "catalog" of the normal bacterial makeup of the human body was published in 2012, numerous connections between illness and disturbances in the human microbiota have been found. This week, scientists report yet another: Cancerous tumors in the ascending colon (the part nearest to the small intestine) are characterized by biofilms, which are dense clumps of bacterial cells encased in a self-produced matrix.

"This is the first time that biofilms have been shown to be associated with colon cancer, to our knowledge," says co-author Jessica ...

2014-12-12

PITTSBURGH--An interest in the gender gap between the representations of female candidates in U.S. elections compared to their male counterparts led two University of Pittsburgh professors to take the issue into the laboratory for three years of research.

Associate Professors of Political Science Kristin Kanthak and Jonathan Woon have published an article about the first phase of their research findings. "Women Don't Run? Election Aversion and Candidate Entry" was published online Dec. 2 in the American Journal of Political Science.

"Past research has shown that women ...

2014-12-12

A group of researchers from Recep Tayyip Erdoğan University, Faculty of Fisheries in Turkey discovered a new trout species. The newly described species Salmo kottelati, belongs to the Salmonidae family, which includes salmons, trouts, chars, graylings and freshwater whitefishes.

Salmonids include over 200 species, which have a high economic value because of their taste and famed sporting qualities.

The genus Salmo is widely distributed in rivers and streams of basins of the Marmara, Black, Aegean and Mediterranean seas. The genus is represented by 12 species in ...

2014-12-12

In a contribution to an extraordinary international scientific collaboration the University of Sydney found that genomic 'fossils' of past viral infections are up to thirteen times less common in birds than mammals.

"We found that only found only five viral families have left a footprint in the bird genome (genetic material) during evolution. Our study therefore suggests that birds are either less susceptible to viral invasions or purge them more effectively than mammals," said Professor Edward Holmes, from the University of Sydney's Charles Perkins Centre, School of ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

[Press-News.org] A control knob for fat?

A protein that makes other proteins also regulates fat levels in worms, and may do so in humans