INFORMATION:

Co-authors are Laleh Saadat, Tibor Valyi-Nagy and Dr. Fei Song of UIC; Gal Keren-Aviram and Edward Dratz of Montana State University; and Shruti Bagla, Andrew Morton, Karina Balan and Dr. William Kupsky of Wayne State School of Medicine.

The research was supported by grants R01NS045207 and R01NS058802 from the National Institutes of Health/National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke.

'Microlesions' in epilepsy discovered by novel technique

Genetics and mathematical modeling point to what goes wrong in epilepsy

2014-12-17

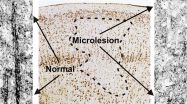

(Press-News.org) Using an innovative technique combining genetic analysis and mathematical modeling with some basic sleuthing, researchers have identified previously undescribed microlesions in brain tissue from epileptic patients. The millimeter-sized abnormalities may explain why areas of the brain that appear normal can produce severe seizures in many children and adults with epilepsy.

The findings, by researchers at the University of Illinois at Chicago College of Medicine, Wayne State University and Montana State University, are reported in the journal Brain.

Epilepsy affects about 1 percent of people worldwide. Its hallmark is unpredictable seizures that occur when groups of neurons in the brain abnormally fire in unison. Sometimes epilepsy can be traced back to visible abnormalities in the brain where seizures start, but in many cases, there are no clear abnormalities or scaring that would account for the epileptic activity.

"Understanding what is wrong in human brain tissues that produce seizures is critical for the development of new treatments because roughly one third of patients with epilepsy don't respond to our currently available medications," said Dr. Jeffrey Loeb, professor and head of neurology and rehabilitation in the UIC College of Medicine and corresponding author on the study. "Knowing these microlesions exist is as huge step forward in our understanding of human epilepsy and present new targets for treating this disease."

Loeb and colleagues searched for cellular changes associated with epilepsy by analyzing thousands genes in tissues from 15 patients who underwent surgery to treat their epilepsy. They used a mathematical modeling technique called cluster analysis to sort through huge amounts of genetic data.

Using the model, they were able to predict and then confirm the presence of tiny regions of cellular abnormalities - the microlesions - in human brain tissue with high levels of epileptic electrical activity, or 'high-spiking' areas where seizures begin.

"Using cluster analysis is like using a metal detector to find a needle in a haystack," said Loeb. The model, he said, revealed 11 gene clusters that "jumped right out at us" and were either up-regulated or down-regulated in tissue with high levels of epileptic electrical activity compared to tissue with less epileptic activity from the same patient.

When they matched the genes to the types of cells they came from, the results predicted that there would be reductions of certain types of neurons and increases in blood vessels and inflammatory cells in brain tissue with high epileptic activity.

When Fabien Dachet, an expert in bioinformatics research at UIC and first author of the study, went back to the tissue samples and stained for these cells, he found that all of the prediction were correct- there was a marked increase in blood vessels, inflammatory cells, and there were focal microlesions made up of neurons that had lost most of their normal connections that allow them to communicate with one another. "We think that these newly found microlesions lead to spontaneous, abnormal electrical currents in the brain that lead to epileptic seizures," said Loeb.

Loeb and his colleagues at UIC are using the same approach to look for the clusters of differentially expressed genes associated with ALS, a neurodegenerative disease, and in brain tumors. "We now have a way to predict cellular changes by simply measuring the genetic composition, with some fairly simple calculations, between more- and less-affected epileptic human tissues," explained Loeb.

"This technique gives us the ability to discover previously unknown cellular abnormalities in almost any disease where we have access to human tissues," Loeb said. He is currently developing at UIC a national 'neurorepository' of electrically mapped and genetically analyzed brain tissue for such studies.

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Study reveals abundance of microplastics in the world's deep seas

2014-12-17

The deep sea is becoming a collecting ground for plastic waste, according to research led by scientists from Plymouth University and Natural History Museum.

The new study, published today in Royal Society Open Science, reveals around four billion microscopic plastic fibres could be littering each square kilometre of deep sea sediment around the world.

Marine plastic debris is a global problem, affecting wildlife, tourism and shipping. Yet monitoring over the past decades has not seen its concentration increase at the sea surface or along shorelines, despite experts ...

Research shows Jaws didn't kill his cousin

2014-12-17

New research suggests our jawed ancestors weren't responsible for the demise of their jawless cousins as had been assumed. Instead Dr Robert Sansom from The University of Manchester believes rising sea levels are more likely to blame. His research has been published in the journal Proceedings of the Royal Society B.

He says: "When our jawed vertebrate ancestors overtook their jawless relatives 400 million years ago, it seems that it might not have been through direct competition but instead the inability of our jawless cousins to adapt to changing environmental conditions."

In ...

Pitt team publishes new findings from mind-controlled robot arm project

2014-12-17

In another demonstration that brain-computer interface technology has the potential to improve the function and quality of life of those unable to use their own arms, a woman with quadriplegia shaped the almost human hand of a robot arm with just her thoughts to pick up big and small boxes, a ball, an oddly shaped rock, and fat and skinny tubes.

The findings by researchers at the University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine, published online today in the Journal of Neural Engineering, describe, for the first time, 10-degree brain control of a prosthetic device in which ...

Population Council reports positive acceptability for investigational contraceptive ring

2014-12-17

NEW YORK (16 December 2014) -- The Population Council published new research in the November issue of the journal Contraception demonstrating that an investigational one-year contraceptive vaginal ring containing Nestorone® and ethinyl estradiol was found to be highly acceptable among women enrolled in a Phase 3 clinical trial. Because the perspectives of women are critical for defining acceptability, researchers developed a theoretical model based on women's actual experiences with this contraceptive vaginal ring, and assessed their overall satisfaction and adherence ...

Traffic stops and DUI arrests linked most closely to lower drinking and driving

2014-12-16

American states got tough on impaired driving in the 1980s and 1990s, but restrictions have flat lined.

A new study looks at associations between levels and types of law-enforcement efforts and prevalence of drinking and driving.

The number of traffic stops and DUI arrests per capita had the most consistent and significant associations.

From 1982 to 1997, American states got tough on impaired driving. Policies favored adopting lower blood alcohol concentration (BAC) limits for driving, administrative license revocation (ALR), and increased sanctions for those convicted ...

Density of alcohol outlets in rural areas depends on the town's average income

2014-12-16

Alcohol outlets tend to be concentrated in lower-income areas. Given that alcohol-related problems such as trauma, chronic disease, and suicide occur more frequently in areas with a greater density of alcohol outlets, lower-income populations are exposed to increased risk. This study examines the distribution of rural outlets in the state of Victoria, Australia, finding towns had more outlets of all types where the average income was lower and where the average income in adjacent towns was higher, and that this was consistent with retail market dynamics.

Results will ...

Alcohol blackouts: Not a joke

2014-12-16

The heaviest drinking and steepest trajectory of increasing alcohol problems are typically observed during the mid-teens to mid-20s. One common and adverse consequence is the alcohol-related blackout (ARB), which is reported by up to 50 percent of drinkers. However, there are few studies of the trajectories of ARBs over time during mid-adolescence. A new study identifying different trajectories of ARBs between ages 15 and 19, along with predictors of those patterns, has found that certain adolescents with particular characteristics are more likely to drink to the point ...

Low-glycemic index carbohydrate diet does not improve CV risk factors, insulin resistance

2014-12-16

In a study that included overweight and obese participants, those with diets with low glycemic index of dietary carbohydrate did not have improvements in insulin sensitivity, lipid levels, or systolic blood pressure, according to a study in the December 17 issue of JAMA.

Foods that have similar carbohydrate content can differ in the amount they raise blood glucose, a property called the glycemic index. Even though some nutrition policies advocate consumption of low-glycemic index foods and even promote food labeling with glycemic index values, the independent benefits ...

Effectiveness of drugs to prevent hepatitis among patients receiving chemotherapy

2014-12-16

Among patients with lymphoma undergoing a certain type of chemotherapy, receiving the antiviral drug entecavir resulted in a lower incidence of hepatitis B virus (HBV)-related hepatitis and HBV reactivation, compared with the antiviral drug lamivudine, according to a study in the December 17 issue of JAMA.

Hepatitis B virus reactivation is a welldocumented chemotherapy complication, with diverse manifestations including life-threatening liver failure, as well as delays in chemotherapy or premature termination, all of which can jeopardize clinical outcomes. The reported ...

How music class can spark language development

2014-12-16

EVANSTON, Ill. - Music training has well-known benefits for the developing brain, especially for at-risk children. But youngsters who sit passively in a music class may be missing out, according to new Northwestern University research.

In a study designed to test whether the level of engagement matters, researchers found that children who regularly attended music classes and actively participated showed larger improvements in how the brain processes speech and reading scores than their less-involved peers after two years.

The research, which appears online on Dec. ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Many patients want to talk about their faith. Neurologists often don't know how.

AI disclosure labels may do more harm than good

The ultra-high-energy neutrino may have begun its journey in blazars

Doubling of new prescriptions for ADHD medications among adults since start of COVID-19 pandemic

“Peculiar” ancient ancestor of the crocodile started life on four legs in adolescence before it began walking on two

AI can predict risk of serious heart disease from mammograms

New ultra-low-cost technique could slash the price of soft robotics

Increased connectivity in early Alzheimer’s is lowered by cancer drug in the lab

Study highlights stroke risk linked to recreational drugs, including among young users

Modeling brain aging and resilience over the lifespan reveals new individual factors

ESC launches guidelines for patients to empower women with cardiovascular disease to make informed pregnancy health decisions

Towards tailor-made heat expansion-free materials for precision technology

New research delves into the potential for AI to improve radiology workflows and healthcare delivery

Rice selected to lead US Space Force Strategic Technology Institute 4

A new clue to how the body detects physical force

Climate projections warn 20% of Colombia’s cocoa-growing areas could be lost by 2050, but adaptation options remain

New poll: American Heart Association most trusted public health source after personal physician

New ethanol-assisted catalyst design dramatically improves low-temperature nitrogen oxide removal

New review highlights overlooked role of soil erosion in the global nitrogen cycle

Biochar type shapes how water moves through phosphorus rich vegetable soils

Why does the body deem some foods safe and others unsafe?

Report examines cancer care access for Native patients

New book examines how COVID-19 crisis entrenched inequality for women around the world

Evolved robots are born to run and refuse to die

Study finds shared genetic roots of MS across diverse ancestries

Endocrine Society elects Wu as 2027-2028 President

Broad pay ranges in job postings linked to fewer female applicants

How to make magnets act like graphene

The hidden cost of ‘bullshit’ corporate speak

Greaux Healthy Day declared in Lake Charles: Pennington Biomedical’s Greaux Healthy Initiative highlights childhood obesity challenge in SWLA

[Press-News.org] 'Microlesions' in epilepsy discovered by novel techniqueGenetics and mathematical modeling point to what goes wrong in epilepsy