(Press-News.org) Berkeley -- Engineers at the University of California, Berkeley, are developing a new type of bandage that does far more than stanch the bleeding from a paper cut or scraped knee. Thanks to advances in flexible electronics, the researchers, in collaboration with colleagues at UC San Francisco, have created a new "smart bandage" that uses electrical currents to detect early tissue damage from pressure ulcers, or bedsores, before they can be seen by human eyes - and while recovery is still possible.

"We set out to create a type of bandage that could detect bedsores as they are forming, before the damage reaches the surface of the skin," said Michel Maharbiz, a UC Berkeley associate professor of electrical engineering and computer sciences and head of the smart-bandage project. "We can imagine this being carried by a nurse for spot-checking target areas on a patient, or it could be incorporated into a wound dressing to regularly monitor how it's healing."

The researchers exploited the electrical changes that occur when a healthy cell starts dying. They tested the thin, non-invasive bandage on the skin of rats and found that the device was able to detect varying degrees of tissue damage consistently across multiple animals.

Tackling a growing health problem

The findings, to be published Tuesday, March 17, in the journal Nature Communications, could provide a major boost to efforts to stem a health problem that affects an estimated 2.5 million U.S. residents at an annual cost of $11 billion.

Pressure ulcers, or bedsores, are injuries that can result after prolonged pressure cuts off adequate blood supply to the skin. Areas that cover bony parts of the body, such as the heels, hips and tailbone, are common sites for bedsores. Patients who are bedridden or otherwise lack mobility are most at risk.

"By the time you see signs of a bedsore on the surface of the skin, it's usually too late," said Dr. Michael Harrison, a professor of surgery at UCSF and a co-investigator of the study. "This bandage could provide an easy early-warning system that would allow intervention before the injury is permanent. If you can detect bedsores early on, the solution is easy. Just take the pressure off."

Bedsores are associated with deadly septic infections, and recent research has shown that odds of a hospital patient dying are 2.8 times higher when they have pressure ulcers. The growing prevalence of diabetes and obesity has increased the risk factors for bedsores.

"The genius of this device is that it's looking at the electrical properties of the tissue to assess damage. We currently have no other way to do that in clinical practice," said Harrison. "It's tackling a big problem that many people have been trying to solve in the last 50 years. As a clinician and someone who has struggled with this clinical problem, this bandage is great."

Cells as capacitors and resistors

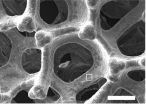

The researchers printed an array of dozens of electrodes onto a thin, flexible film. They discharged a very small current between the electrodes to create a spatial map of the underlying tissue based upon the flow of electricity at different frequencies, a technique called impedance spectroscopy.

The researchers pointed out that a cell's membrane is relatively impermeable when functioning properly, thus acting like an insulator to the cell's conductive contents and drawing the comparison to a capacitor. As a cell starts to die, the integrity of the cell wall starts to break down, allowing electrical signals to leak through, much like a resistor.

"Our device is a comprehensive demonstration that tissue health in a living organism can be locally mapped using impedance spectroscopy," said study lead author Sarah Swisher, a Ph.D. candidate in electrical engineering and computer sciences at UC Berkeley.

To mimic a pressure wound, the researchers gently squeezed the bare skin of rats between two magnets. They left the magnets in place for one or three hours while the rats resumed normal activity. The resumption of blood flow after the magnets were removed caused inflammation and oxidative damage that accelerated cell death. The smart bandage was used to collect data once a day for at least three days to track the progress of the wounds.

The smart bandage was able to detect changes in electrical resistance consistent with increased membrane permeability, a mark of a dying cell. Not surprisingly, one hour of pressure produced mild, reversible tissue damage while three hours of pressure produced more serious, permanent injury.

Promising future

"One of the things that makes this work novel is that we took a comprehensive approach to understanding how the technique could be used to observe developing wounds in complex tissue," said Swisher. "In the past, people have used impedance spectroscopy for cell cultures or relatively simple measurements in tissue. What makes this unique is extending that to detect and extract useful information from wounds developing in the body. That's a big leap."

Maharbiz said the outlook for this and other smart bandage research is bright.

"As technology gets more and more miniaturized, and as we learn more and more about the responses the body has to disease and injury, we're able to build bandages that are very intelligent," he said. "You can imagine a future where the bandage you or a physician puts on could actually report a lot of interesting information that could be used to improve patient care."

INFORMATION:

Other lead researchers on the project include Vivek Subramanian and Ana Claudia Arias, both faculty members in UC Berkeley's Department of Electrical Engineering and Computer Sciences; and Shuvo Roy, a UCSF professor of bioengineering. Additional co-authors include Amy Liao and Monica Lin, both UC Berkeley Ph.D. students in bioengineering.

Study co-author Dr. David Young, UCSF professor of surgery, is now heading up a clinical trial of this bandage.

The project is funded through the Flexible Resorbable Organic and Nanomaterial Therapeutic Systems (FRONTS) program of the National Science Foundation.

UNSW Australia scientists have developed a highly efficient oxygen-producing electrode for splitting water that has the potential to be scaled up for industrial production of the clean energy fuel, hydrogen. The new technology is based on an inexpensive, specially coated foam material that lets the bubbles of oxygen escape quickly.

"Our electrode is the most efficient oxygen-producing electrode in alkaline electrolytes reported to date, to the best of our knowledge," says Associate Professor Chuan Zhao, of the UNSW School of Chemistry.

"It is inexpensive, sturdy and simple ...

Tuesday, March 17, 2015. Just like milk and many other foods, blood used for transfusions is perishable. But contrary to popular belief, new research shows that blood stored for three weeks is just as good as fresh blood - findings published today in the New England Journal of Medicine.

The large clinical trial provides reassuring evidence about the safety of blood routinely transfused to critically ill patients. Supported by the Canadian Critical Care Trials Group and countless nurses, blood bank technologists, transfusion medicine and critical care physicians, Drs. ...

Ann Arbor, MI, March 17, 2015 -- Suicide is responsible for more than 36,000 deaths in the United States and nearly 1 million deaths worldwide annually. In 2009, suicides surpassed motor vehicle crashes as the leading cause of death by injury in the U.S. A new study published in the American Journal of Preventive Medicine analyzes the upward trend of suicides that take place in the workplace and identifies specific occupations in which individuals are at higher risk. The highest workplace suicide rate is in protective services occupations (5.3 per 1 million), more than ...

(Chicago) - Just as humans will travel to their favorite restaurant, chimpanzees will travel a farther distance for preferred food sources in non-wild habitats, according to a new study from scientists at Chicago's Lincoln Park Zoo that publishes on March 17 in the journal PeerJ.

Chimpanzees at Lincoln Park Zoo prefer grapes over carrots. Previous research at the zoo provided that insight into food preferences. Now, a 15-month study, led by Lydia Hopper, PhD of the Lester Fisher Center for the Study and Conservation of Apes at Lincoln Park Zoo, suggests that the apes ...

Toronto, ON (March 17, 2015) - A comprehensive study examining clinical trials of more than 95,000 patients has found that glucose or sugar-lowering medications prescribed to patients with diabetes may pose an increased risk for the development of heart failure in these patients.

"Patients randomized to new or more intensive blood sugar-lowering drugs or strategies to manage diabetes showed an overall 14 per cent increased risk for heart failure," says Dr. Jacob Udell, the study's principal investigator, and cardiologist at the Peter Munk Cardiac Centre, University Health ...

A new study, "Global Dispersion and Local Diversification of the Methane Seep Microbiome," provides evidence methane seeps are habitats that harbor distinct microbial communities unique from other seafloor ecosystems. The article appeared in the March 16 issue of the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS).

Methane seeps are natural gas leaks in the sea floor that emit methane into the water. Microorganisms that live on or near these seeps can use the methane as a food source, preventing the gas from collecting in the surrounding hydrosphere or migrating ...

If you want someone to open up to you, just make them laugh. Sharing a few good giggles and chuckles makes people more willing to tell others something personal about themselves, without even necessarily being aware that they are doing so. These are among the findings of a study led by Alan Gray of University College London in the UK, published in Springer's journal Human Nature.

The act of verbally opening up to someone is a crucial building block that helps to form new relationships and intensify social bonds. Such self-disclosure can be of a highly sensitive nature ...

Charles R. Wira, PhD, and colleagues at Dartmouth's Geisel School of Medicine have presented a comprehensive review of the role of sex hormones in the geography of the female reproductive tract and evidence supporting a "window of vulnerability" to HIV and other sexually transmitted infections (STIs). Published in Nature Reviews in Immunology, Wira's team presents a body of work that National Institutes of Health evaluators called, "a sea change" for research in the female reproductive tract (FRT).

"The FRT is tremendously complex and the normal changes that occur to ...

The studies below will be presented at the American College of Cardiology's 64th Annual Scientific Session on Monday, March 16.

1. New Insights on Endurance Sports and Atrial Fibrillation

Previous studies have suggested endurance athletes may face a slightly higher risk of developing atrial fibrillation, a condition in which the heartbeat becomes irregular or rapid. A new study shows that among runners, the total number of years a person has been running is the factor most closely associated with atrial fibrillation risk, as compared to other measures of running behavior ...

To pack two meters of DNA into a microscopic cell, the string of genetic information must be wound extremely carefully into chromosomes. Surprisingly the DNA's sequence causes it to be coiled and uncoiled much like a yoyo, scientists reported in Cell.

"We discovered this interesting physics of DNA that its sequence determines the flexibility and thus the stability of the DNA package inside the cell," said Gutgsell Professor of Physics Taekjip Ha, who is a member of the Carl R. Woese Institute for Genomic Biology at the University of Illinois. "This is actually very elementary ...