(Press-News.org) There's a carbon showdown brewing in the Arctic as Earth's climate changes. On one side, thawing permafrost could release enormous amounts of long-frozen carbon into the atmosphere. On the opposing side, as high-latitude regions warm, plants will grow more quickly, which means they'll take in more carbon from the atmosphere.

Whichever side wins will have a big impact on the carbon cycle and the planet's climate. If the balance tips in favor of permafrost-released carbon, climate change could accelerate. If the balance tips in favor of carbon-consuming plants, climate change could slow down.

Turns out the result will be lopsided. There will be a lot more carbon released from thawing permafrost than the amount taken in by more Arctic vegetation, according to new computer simulations conducted by scientists from the U.S. Department of Energy's Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (Berkeley Lab).

The findings are from an Earth system model that is the first to represent permafrost processes as well as the dynamics of carbon and nitrogen in the soil. Simulations using the model showed that by the year 2300, if climate change continues unchecked, the net loss of carbon to the atmosphere from Arctic permafrost would range from between 21 petagrams and 164 petagrams. That's equivalent to between two years and 16 years of human-induced CO2 emissions.

The scientists included nitrogen dynamics in the model because, as permafrost thaws, nitrogen trapped in deeper soil layers (below one meter underground) will decompose and become available to fertilize plants. At the same time, organic carbon frozen in deeper soil layers will decompose and enter the atmosphere.

"The big question has been: Which side wins? And we found the rate of permafrost thaw and its effect on the decomposition of deep carbon will have a much bigger impact on the carbon cycle than the availability of deep nitrogen and its ability to spark plant growth," says Charles Koven of Berkeley Lab's Earth Sciences Division.

Koven conducted the research with fellow Berkeley Lab scientist William Riley and David Lawrence of the National Center for Atmospheric Research. They recently reported their research in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

The scientists believe that nitrogen's relatively small impact on the carbon cycle is due to the fact that deeper layers of permafrost won't thaw until the fall or even early winter, when summer's warmth finally reaches more than one meter below ground. At that stage in the growing season, the deep nitrogen that decomposes and becomes available will have few plants to fertilize.

The model's output also highlights uncertainties in the science. After all, the simulations found that between 21 petagrams and 164 petagrams of carbon will be released to the atmosphere, which is a big range. The scientists say that more field and lab research is needed to determine how carbon-decomposition dynamics work in deep layers of permafrost versus at the surface, including the role of microbes, minerals, and plant roots.

"These simulations allow us to identify processes that seem to have a lot of leverage on climate change, and which we need to explore further," says Koven.

INFORMATION:

The terrestrial ecosystem portion of the Earth system model simulations were conducted at the National Energy Research Scientific Computing Center (NERSC), a DOE Office of Science User Facility located at Berkeley Lab.

The research was supported by the Department of Energy's Office of Science.

Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory addresses the world's most urgent scientific challenges by advancing sustainable energy, protecting human health, creating new materials, and revealing the origin and fate of the universe. Founded in 1931, Berkeley Lab's scientific expertise has been recognized with 13 Nobel prizes. The University of California manages Berkeley Lab for the U.S. Department of Energy's Office of Science. For more, visit http://www.lbl.gov.

DOE's Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States, and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, please visit the Office of Science website at science.energy.gov/.

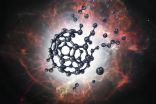

In 1996, a trio of scientists won the Nobel Prize for Chemistry for their discovery of Buckminsterfullerene - soccer-ball-shaped spheres of 60 joined carbon atoms that exhibit special physical properties.

Now, 20 years later, scientists have figured out how to turn them into Buckybombs.

These nanoscale explosives show potential for use in fighting cancer, with the hope that they could one day target and eliminate cancer at the cellular level - triggering tiny explosions that kill cancer cells without affecting surrounding tissue.

"Future applications would probably ...

BLOOMINGTON, Ind. -- An Indiana University cognitive scientist and collaborators have found that posture is critical in the early stages of acquiring new knowledge.

The study, conducted by Linda Smith, a professor in the IU Bloomington College of Arts and Sciences' Department of Psychological and Brain Sciences, in collaboration with a roboticist from England and a developmental psychologist from the University of Wisconsin-Madison, offers a new approach to studying the way "objects of cognition," such as words or memories of physical objects, are tied to the position ...

For generations, students have been taught the concept of "ecological succession" with examples from the plant world, such as the progression over time of plant species that establish and grow following a forest fire. Indeed, succession is arguably plant ecology's most enduring scientific contribution, and its origins with early 20th-century plant ecologists have been uncontested. Yet, this common narrative may actually be false. As posited in an article published in the March 2015 issue of The Quarterly Review of Biology, two decades before plant scientists explored the ...

Tirat Carmel, Israel - March 19, 2015 - MeMed, Ltd., today announced publication of the results of a large multicenter prospective clinical study that validates the ability of its ImmunoXpert in-vitro diagnostic blood test to determine whether a patient has an acute bacterial or viral infection. The study enrolled more than 1,000 patients and is published in the March 18, 2015 online edition of PLOS ONE. Unlike most infectious disease diagnostics that rely on direct pathogen detection, MeMed's assay decodes the body's immune response to accurately characterize the cause ...

The most extensive land-based study of the Amazon to date reveals it is losing its capacity to absorb carbon from the atmosphere. From a peak of two billion tonnes of carbon dioxide each year in the 1990s, the net uptake by the forest has halved and is now for the first time being overtaken by fossil fuel emissions in Latin America.

The results of this monumental 30-year survey of the South American rainforest, which involved an international team of almost 100 researchers and was led by the University of Leeds, are published today in the journal Nature.

Over recent ...

Messenger RNAs (mRNA) are linear molecules that contain instructions for producing the proteins that keep living cells functioning. A new study by UCL researchers has shown how the three-dimensional structures of mRNAs determine their stability and efficiency inside cells. This new knowledge could help to explain how seemingly minor mutations that alter mRNA structure might cause things to go wrong in neurodegenerative diseases like Alzheimer's.

mRNAs carry genetic information from DNA to be translated into proteins. They are generated as long chains of molecules, but ...

Many people in the UK feel a strong sense of regional identity, and it now appears that there may be a scientific basis to this feeling, according to a landmark new study into the genetic makeup of the British Isles.

An international team, led by researchers from the University of Oxford, UCL (University College London) and the Murdoch Childrens Research Institute in Australia, used DNA samples collected from more than 2,000 people to create the first fine-scale genetic map of any country in the world.

Their findings, published in Nature, show that prior to the mass ...

DURHAM, N.C. -- Each year, rice in Asia faces a big threat from a sesame seed-sized insect called the brown planthopper. Now, a study reveals the molecular switch that enables some planthoppers to develop short wings and others long -- a major factor in their ability to invade new rice fields.

The findings will appear Mar. 18 in the journal Nature.

Lodged in the stalks of rice plants, planthoppers use their sucking mouthparts to siphon sap. Eventually the plants turn yellow and dry up, a condition called "hopper burn."

Each year, planthopper outbreaks destroy hundreds ...

Researchers have linked antibiotic resistance with poor governance and corruption around the world.

Lead researcher Professor Peter Collignon from The Australian National University (ANU) School of Medicine said the increase in antibiotic-resistant infections was one of the greatest threats facing modern medicine.

In the United States alone, around 23,000 deaths and two million illnesses each year have been attributed to antibiotic-resistant bacteria.

"We found poor governance and higher levels of corruption are associated with higher levels of antibiotic resistance," ...

COLUMBUS, Ohio - Cardiovascular researchers at The Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center have shown that a protein known as MG53 is not only present in kidney cells, but necessary for the organ to repair itself after acute injury. Results from this animal model study are published in the journal Science Translational Medicine.

Previous work by Jianjie Ma, a professor and researcher in Ohio State's Department of Surgery and the Dorothy M. Davis Heart & Lung Research Institute, identified and proved that MG53 repairs heart, lung and skeletal muscle cells as well.

"MG53 ...