(Press-News.org) DURHAM, N.C. - Scientists have known for some time that people who carry a lot of weight around their bellies are more likely to develop diabetes and heart disease than those who have bigger hips and thighs. But what hasn't been clear is why fat accumulates in different places to produce these classic "apple" and "pear" shapes.

Now, researchers have discovered that a gene called Plexin D1 appears to control both where fat is stored and how fat cells are shaped, known factors in health and the risk of future disease.

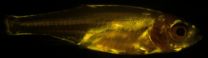

Acting on a pattern that emerged in an earlier study of waist-to-hip ratios in 224,000 people, the study, which appears March 23 in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, found that zebrafish that were missing the Plexin D1 gene had less abdominal or visceral fat, the kind that lends some humans a characteristic apple shape. The researchers also showed that these mutant zebrafish were protected from insulin resistance, a precursor of diabetes, even after eating a high-fat diet.

"This work identifies a new molecular pathway that determines how fat is stored in the body, and as a result, affects overall metabolic health," said John F. Rawls, Ph.D., senior author of the study and associate professor of molecular genetics and microbiology at Duke University School of Medicine. "Moving forward, the components of that pathway can become potential targets to address the dangers associated with visceral fat accumulation."

Unlike the subcutaneous fat that sits beneath the skin of the hips, thighs, and rear of pear-shaped individuals, visceral fat lies deep within the midsection, wedged between vital organs like the heart, liver, intestine, and lungs. From there, the tissue emits hormones and other chemicals that cause inflammation, triggering metabolic diseases like high blood pressure, heart attack, stroke, and diabetes.

Despite the clear health implications of body fat distribution, relatively little is known about the genetic basis of body shape. A large international study that appeared in Nature in February began to fill in this gap by looking for regions of the human genome associated with a common metric known as the waist-to-hip ratio, which uses waist measurements as a proxy for visceral fat and hip measurements as a proxy for subcutaneous fat. The researchers analyzed samples from 224,000 people and found dozens of hot spots linked to their waist-hip ratio, including a few near a gene called Plexin D1 which is known to be involved in building blood vessels.

Rawls and his postdoctoral fellow James E. Minchin, Ph.D., were curious about how a gene for growing blood vessels might control the storage and shape of fat cells. When they knocked out the Plexin D1 gene in mice, all of the mutant animals died at birth. So they turned to another model organism, the zebrafish, to conduct the rest of their experiments. Because these small aquarium fish are transparent for much of their lives, the researchers could directly visualize how fat was distributed differently between animals that had been genetically engineered to lack Plexin D1 and those with the gene still intact.

By using a chemical dye that fluorescently stained all fat cells, the researchers could see that the mutant zebrafish had less visceral fat than their normal counterparts. They also noticed that the shape or morphology of the fat cells themselves was different. The zebrafish without the Plexin D1 gene had visceral fat tissue that was composed of smaller, but more numerous cells, a characteristic known to decrease the risk of insulin resistance and metabolic disease in humans. In contrast, their normal siblings had visceral fat tissue containing larger, but fewer fat cells of the kind known to be more likely to leak inflammatory substances that contribute to illness.

To determine how these findings related to metabolic disease, Minchin put the zebrafish on a high-fat diet. After a few weeks of adding egg yolks to their typical chow, Minchin found that the differences in fat distribution between the mutant and the normal zebrafish became even more pronounced. He then gave the fish a glucose tolerance test to see how their bodies responded to sugar. The mutants did a better job of clearing sugar out of their bloodstream and seemed to be protected from developing insulin resistance, a risk factor for diabetes and heart disease.

Bolstering the zebrafish findings, collaborators at the Karolinska Institute in Sweden analyzed human patient samples and showed that levels of Plexin D1 were higher in individuals with type 2 diabetes, suggesting it may play a similar role in humans.

"We think that Plexin D1 is functioning within blood vessels to pattern the environment in visceral fat tissue," said Minchin, who was lead author of the study. That is, the genes that build blood vessels are also setting up structures to house fat cells. "And this role skews the distribution and shape of fat in one direction or another," he said. "It is probably just one of many of different genes that each contribute to overall body shape and metabolic health."

The researchers are actively searching for other genes as well as environmental factors that are involved in the biology of body fat, again using zebrafish models.

"Our results indicate that the genetic architecture of body fat distribution is shared between fish and humans, which represents about 450 million years of evolutionary divergence," Rawls said. "For these pathways to have been conserved for so long suggests that they are serving an important role."

INFORMATION:

The research was supported in part by grants from the National Institutes of Health (DK081426, DK091356, DK093399, HL092263, R01HL118768), UNC UCRF Pilot Research Project Award, a Pew Scholars in Biomedical Sciences Award, and American Heart Association Postdoctoral Fellowships (11POST7360004, 13POST1690097).

CITATION: "Plexin D1 determines body fat distribution by regulating the type V collagen microenvironment in visceral adipose tissue," James E.N. Minchin, Ingrid Dahlman, Christopher J. Harvey, Niklas Mejhert, Manvendra K. Singh, Jonathan A. Epstein, Jesús Torres-Vázquez, and John F. Rawls. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, March 23, 2015. DOI: 10.1073/pnas.1416412112

(MEMPHIS, Tenn. -- MARCH 23, 2015) Research led by scientists at St. Jude Children's Research Hospital has identified key molecules that trigger the immune system to launch an attack on the bacterium that causes tularemia. The research was published online March 16 in Nature Immunology.

The team, led by Thirumala-Devi Kanneganti, Ph.D., a member of the St. Jude Department of Immunology, found key receptors responsible for sensing DNA in cells infected by the tularemia-causing bacterium, Francisella. Tularemia is a highly infectious disease that kills more than 30 percent ...

MAYWOOD, Ill. - No cures are possible for most patients who suffer debilitating movement disorders called cerebellar ataxias.

But in a few of these disorders, patients can be effectively treated with regimens such as prescription drugs, high doses of vitamin E and gluten-free diets, according to a study in the journal Movement Disorders.

"Clinicians must become familiar with these disorders, because maximal therapeutic benefit is only possible when done early. These uncommon conditions represent a unique opportunity to treat incurable and progressive diseases," first ...

Contrary to the statistician's slogan, in the quantum world, certain kinds of correlations do imply causation.

Research from the Institute for Quantum Computing (IQC) at the University of Waterloo and the Perimeter Institute for Theoretical Physics shows that in quantum mechanics, certain kinds of observations will let you distinguish whether there is a common cause or a cause-effect relation between two variables. The same is not true in classical physics.

Explaining the observed correlations among a number of variables in terms of underlying causal mechanisms, known ...

A surgical sedative may hold the key to reversing the devastating symptoms of a neurodevelopmental disorder found almost exclusively in females. Ketamine, used primarily for operative procedures, has shown such promise in mouse models that Case Western Reserve and Cleveland Clinic researchers soon will launch a two-year clinical trial using low doses of the medication in up to 35 individuals with Rett Syndrome.

The $1.3 million grant from Rett Syndrome Research Trust (RSRT) represents a landmark step in area researchers' efforts to create a true regional collaborative ...

When an earthquake hits, the faster first responders can get to an impacted area, the more likely infrastructure--and lives--can be saved.

New research from the University of Iowa, along with the United States Geological Survey (USGS), shows that GPS and satellite data can be used in a real-time, coordinated effort to fully characterize a fault line within 24 hours of an earthquake, ensuring that aid is delivered faster and more accurately than ever before.

Earth and Environmental Sciences assistant professor William Barnhart used GPS and satellite measurements from ...

In addition to antiretroviral medications, people with HIV may soon begin receiving a home exercise plan from their doctors, according to a researcher at Case Western Reserve University's Frances Payne Bolton School of Nursing.

"People with HIV are developing secondary chronic illnesses earlier and more frequently than their non-HIV counterparts," said Allison Webel, PhD, RN, assistant professor of nursing. "And heart disease is one for which they are especially at risk."

An estimated 1.2 million people nationally live with HIV, according to the Centers for Disease ...

Today, ACS is launching its first open access multidisciplinary research journal. Aspiring to communicate the most novel and impactful science developments, ACS Central Science will feature peer-reviewed articles reporting on timely original research across chemistry and its allied sciences. Free to readers and authors alike, original research content will be accompanied by additional editorial features.

These additional editorial features include news stories contributed by the Society's award-winning science journalists, invited topical reviews (called Outlooks) from ...

Young children who received the 4CMenB vaccine as infants to protect against serogroup B meningococcal disease had waning immunity by age 5, even after receiving a booster at age 3 ½, according to new research in CMAJ (Canadian Medical Association Journal)

Serogroup B meningococcal disease is the leading cause of meningitis and blood infections in developed countries. Infants and young children under the age of 5 years are especially at risk, and there is a second peak of cases in the late teenage years.

The multicomponent serogroup B meningococcal (4CMenB) ...

COLUMBUS, Ohio--Researchers at The Ohio State University have discovered how to control heat with a magnetic field.

In the March 23 issue of the journal Nature Materials, they describe how a magnetic field roughly the size of a medical MRI reduced the amount of heat flowing through a semiconductor by 12 percent.

The study is the first ever to prove that acoustic phonons--the elemental particles that transmit both heat and sound--have magnetic properties.

"This adds a new dimension to our understanding of acoustic waves," said Joseph Heremans, Ohio Eminent Scholar ...

New observations made with APEX and other telescopes reveal that the star that European astronomers saw appear in the sky in 1670 was not a nova, but a much rarer, violent breed of stellar collision. It was spectacular enough to be easily seen with the naked eye during its first outburst, but the traces it left were so faint that very careful analysis using submillimetre telescopes was needed before the mystery could finally be unravelled more than 340 years later. The results appear online in the journal Nature on 23 March 2015.

Some of seventeenth century's greatest ...