How oxytocin makes a mom: Hormone teaches maternal brain to respond to offspring's needs

Research could lead to advanced treatments for social anxiety, post-traumatic stress disorder and other brain behavioral issues

2015-04-15

(Press-News.org) Neuroscientists at NYU Langone Medical Center have discovered how the powerful brain hormone oxytocin acts on individual brain cells to prompt specific social behaviors - findings that could lead to a better understanding of how oxytocin and other hormones could be used to treat behavioral problems resulting from disease or trauma to the brain. The findings are to be published in the journal Nature online April 15.

Until now, researchers say oxytocin -- sometimes called the "pleasure hormone" -- has been better known for its role in inducing sexual attraction and orgasm, regulating breast feeding and promoting maternal-infant bonding. But its precise levers for controlling social behaviors were not known.

"Our findings redefine oxytocin as something completely different from a 'love drug,' but more as an amplifier and suppressor of neural signals in the brain," says study senior investigator Robert Froemke, PhD, an assistant professor at NYU Langone and its Skirball Institute of Biomolecular Medicine. "We found that oxytocin turns up the volume of social information processed in the brain. This suggests that it could one day be used to treat social anxiety, post-traumatic stress disorder, speech and language disorders, and even psychological issues stemming from child abuse."

In experiments in mice, Dr. Froemke and his team mapped oxytocin to unique receptor cells in the left side of the brain's cortex. They found that the hormone controls the volume of "social information" processed by individual neurons, curbing so-called excitatory or inhibitory signals -- and immediately determining how female mice with pups responded to cries for help and attention.

In separate experiments in adult female mice with no pups -- and hence no experience with elevated oxytocin levels -- adding extra oxytocin into their "virgin" brains led these mice to quickly recognize the barely audible distress calls of another mother's pups recently removed from their home nest. These adult mice quickly learned to set about fetching the pups, picking them up by the scruffs of their necks and returning them to the nest - all as if they were the pups' real mother.

This learned behavior was permanent, researchers say; the mice with no offspring continued to retrieve pups even when their oxytocin receptors were later blocked.

According to lead study investigator Bianca Marlin, PhD, a postdoctoral research fellow at NYU Langone: "It was remarkable to watch how adding oxytocin shifted animal behavior, as mice that didn't know how to perform a social task could suddenly do it perfectly."

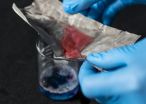

Key to the researchers' efforts to track oxytocin at work in individual brain cells was use of an antibody developed at NYU Langone that specifically binds to oxytocin-receptor proteins on each neuron, allowing the cells to be seen with a microscope.

"Our future research includes further experiments to understand the natural conditions, beyond childbirth, under which oxytocin is released in the brain," Dr. Froemke adds.

INFORMATION:

Funding support for the study was provided by the National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders and the National Institute of Mental Health, both members of the National Institutes of Health. Corresponding grant numbers are DC009635, DC12557, and T32 MH019524. Additional funding was provided by McKnight and Pew scholarships; Sloan and NYU-Whitehead research fellowships; and a Skirball Institute collaborative research award.

Other researchers involved in the study, conducted entirely at NYU Langone, were Mariela Mitre, BE; James D'amour, BSc; and Moses Chao, PhD, whose laboratory developed the oxytocin receptor antibody used to track hormone activity.

For more information, go to:

http://skirball.med.nyu.edu/faculty/az/froemke-robert-c

http://froemkelab.med.nyu.edu/research

http://nature.com/articles/doi:10.1038/nature14402

Media Contact:

David March

212.404.3528

david.march@nyumc.org

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

2015-04-15

Previous studies have suggested that pulses of icebergs may have caused cycles of abrupt climate change during the last glacial period by introducing fresh water to the surface of the ocean and changing ocean currents, which are known to play a dominant role in the climate of many of Earth's regions.

However, new findings by scientists at Cardiff University present a contradictory narrative and suggest that icebergs generally arrived too late to trigger marked cooling across the North Atlantic.

Abrupt climate change, characterised by transitions between warm and cold ...

2015-04-15

COLUMBIA, Mo. - Invasive pests known as spruce bark beetles have been attacking Alaskan forests for decades, killing more than 1 million acres of forest on the Kenai Peninsula in southern Alaska for more than 25 years. Beyond environmental concerns regarding the millions of dead trees, or "beetle kill" trees, inhabitants of the peninsula and surrounding areas are faced with problems including dangerous falling trees, high wildfire risks, loss of scenic views and increased soil erosion. Now, a researcher from the University of Missouri and his colleagues have found that ...

2015-04-15

Irvine, Calif., April 15, 2015 -- While recent reports question whether fish oil supplements support heart health, UC Irvine scientists have found that the fatty acids they contain are vitally important to the developing brain.

In a study appearing today in The Journal of Neuroscience, UCI neurobiologists report that dietary deficiencies in the type of fatty acids found in fish and other foods can limit brain growth during fetal development and early in life. The findings suggest that women maintain a balanced diet rich in these fatty acids for themselves during pregnancy ...

2015-04-15

California man Mike May made international headlines in 2000 when his sight was restored by a pioneering stem cell procedure after 40 years of blindness.

But a study published three years after the operation found that the then-49-year-old could see colors, motion and some simple two-dimensional shapes, but was incapable of more complex visual processing.

Hoping May might eventually regain those visual skills, University of Washington researchers and colleagues retested him a decade later. But in a paper now available online in Psychological Science, they report that ...

2015-04-15

NEW YORK (April 15, 2015) -- Weill Cornell Medical College investigators tried to validate a previously reported molecular finding on triple negative breast cancer that many hoped would lead to targeted treatments for the aggressive disease. Instead, they discovered that the findings were limited to a single patient and could not be applied to further clinical work. This discovery, published April 15 in Nature, amends the earlier work and underscores the importance of independent study validation and careful assay development.

The earlier - and now dispelled - study, ...

2015-04-15

GAINESVILLE, Fla. -- Oxycodone-related deaths dropped 25 percent after Florida implemented its Prescription Drug Monitoring Program in late 2011 as part of its response to the state's prescription drug abuse epidemic, according to a team of UF Health researchers. The drop in fatalities could stem from the number of health care providers who used the program's database to monitor controlled substance prescriptions.

"Forty-nine states have prescription drug monitoring programs of some kind, but this is the first study to demonstrate that one of these programs significantly ...

2015-04-15

COLUMBUS, Ohio--The unassuming piece of stainless steel mesh in a lab at The Ohio State University doesn't look like a very big deal, but it could make a big difference for future environmental cleanups.

Water passes through the mesh but oil doesn't, thanks to a nearly invisible oil-repelling coating on its surface.

In tests, researchers mixed water with oil and poured the mixture onto the mesh. The water filtered through the mesh to land in a beaker below. The oil collected on top of the mesh, and rolled off easily into a separate beaker when the mesh was tilted.

The ...

2015-04-15

April 15, 2015 - Most people who attempt suicide make some type of healthcare visit in the weeks or months before the attempt, reports a study in the May issue of Medical Care, published by Wolters Kluwer.

The study also identifies racial/ethnic differences that may help to target suicide prevention efforts in the doctor's office and other health care settings. The lead author was Brian K. Ahmedani, PhD, LMSW, of Henry Ford Health System, Detroit, Mich.

Health Visits May Provide Chances for Suicide Prevention

Using data from the NIMH-funded Mental Health Research ...

2015-04-15

Index shows nearly two points increase in EU overall, but Greece and Latvia fall behind

Sweden tops the table, while UK comes fourth with increase in line with EU average

A healthy and active old age is a reality for many Europeans and is a genuine possibility for many more, despite the 2008 economic crash and years of austerity measures, according to a new United Nations Economic Commission for Europe (UNECE) and European Commission (EC) report, produced at the University of Southampton.

However, countries such as Greece and Latvia have declined in active ageing ...

2015-04-15

New work by Ludwig-Maximilians-Universitaet (LMU) in Munich researchers demonstrates that macrophages can effectively substitute for so-called dendritic cells as primers of T-cell-dependent immune responses. Indeed, they stimulate a broader-based response.

The immune response, the process by which the adaptive immune system reacts to, and eliminates foreign substances and cells, depends on a complex interplay between several different cell types. So-called dendritic cells, which recognize and internalize invasive pathogens, play a crucial role in this process. Inside ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

[Press-News.org] How oxytocin makes a mom: Hormone teaches maternal brain to respond to offspring's needs

Research could lead to advanced treatments for social anxiety, post-traumatic stress disorder and other brain behavioral issues