(Press-News.org) Johns Hopkins scientists have discovered that neurons are risk takers: They use minor "DNA surgeries" to toggle their activity levels all day, every day. Since these activity levels are important in learning, memory and brain disorders, the researchers think their finding will shed light on a range of important questions. A summary of the study will be published online in the journal Nature Neuroscience on April 27.

"We used to think that once a cell reaches full maturation, its DNA is totally stable, including the molecular tags attached to it to control its genes and maintain the cell's identity," says Hongjun Song, Ph.D., a professor of neurology and neuroscience in the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine's Institute for Cell Engineering. "This research shows that some cells actually alter their DNA all the time, just to perform everyday functions."

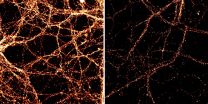

This DNA alteration is called DNA demethylation. Methyl groups are regulatory tags that are permanently bound to cytosines, the C's in DNA's four-letter alphabet. Removing them is a multistep process that requires excising a tagged cytosine from the long string of paired "letters" that make up a chromosome and, ideally, replacing it with an untagged cytosine. Because the process involves making a cut into DNA, it leaves the DNA somewhat vulnerable to mutations, so most cells use the process sparingly, mostly for correcting errors. But recent studies had turned up evidence that mammals' brains exhibit highly dynamic DNA modification activity -- more than in any other area of the body -- and Song's group wanted to know why all this risky business was going on in such a vulnerable tissue as the brain.

The main job of neurons is to communicate with other neurons through connections called synapses. At each synapse, an initiating neuron releases chemical messengers, which are intercepted by receptor proteins on the receiving neuron. Neurons can toggle the "volume" of this communication by adjusting the activity level of their genes to change the number of their messengers or receptors on the surface of the neuron. When Song's team added various drugs to neurons taken from mouse brains, their synaptic activity -- the volume of their communication -- went up and down accordingly. When it was up, so was the activity of the Tet3 gene, which kicks off DNA demethylation. When it was down, Tet3 was down too.

Then, they flipped the experiment around and manipulated the levels of Tet3 in the cells. Surprisingly, when Tet3 levels were up, synaptic activity was down; when Tet3 levels were down, synaptic activity was up. So do Tet3 levels depend on synaptic activity, or is it the other way around?

Another series of experiments showed them that one of the changes occurring in neurons in response to low levels of Tet3 was an increase in the protein GluR1 at their synapses. Since GluR1 is a receptor for chemical messengers, its abundance at synapses is one of the ways neurons can toggle their synaptic activity.

The scientists say they have discovered another mechanism used by neurons to maintain relatively consistent levels of synaptic activity so that neurons can remain responsive to the signaling around them. If synaptic activity increases, Tet3 activity and base excision of tagged cytosines increases. This causes the levels of GluR1 at synapses to decrease, in turn, which decreases their overall strength, bringing the synapses back to their previous activity level. The opposite can also happen, resulting in increasing synaptic activity in response to an initial decrease. So Tet3 levels respond to synaptic activity levels, and synaptic activity levels respond to Tet3 levels.

Song says: "If you shut off neural activity, the neurons 'turn up their volume' to try to get back to their usual level and vice versa. But they can't do it without Tet3."

Song adds that the ability to regulate synapse activity is the most fundamental property of neurons: "It's how our brains form circuits that contain information." Since this synaptic flexibility seems to require mildly risky DNA surgery to work, Song wonders if some brain disorders might arise from neurons losing their ability to "heal" properly after base excision. He thinks this study brings us one step closer to finding out.

INFORMATION:

Other authors of the report include Huimei Yu, Yijin Su, Jaehoon Shin, Chun Zhong, Junjie Guo, Yi-lan Wen and Guo-li Ming of the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine; and Fuying Gao, Daniel Geschwind and Giovanni Coppola of the University of California, Los Angeles.

This work was supported by grants from the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NS047344, NS048271, NS062691), the National Institute of Mental Health (MH105128), the Simons Foundation (SFARI240011), the Brain and Behavior Research Foundation, the Maryland Stem Cell Research Foundation, and the Dr. Miriam and Sheldon G. Adelson Medical Research Foundation.

Eating 3,000 mg per day of salt or more appears to have no adverse effect on blood pressure in adolescent girls, while those girls who consumed 2,400 mg per day or more of potassium had lower blood pressure at the end of adolescence, according to an article published online by JAMA Pediatrics.

The scientific community has historically believed most people in the United States consume too much salt in their diets. The current Dietary Guidelines for Americans recommends limiting sodium intake to less than 2,300 mg per day for healthy individuals between the ages of 2 and ...

Survivors of Hodgkin lymphoma appear to be at higher risk for cardiovascular diseases and both physicians and patients need to be aware of this increased risk, according to an article published online by JAMA Internal Medicine.

Hodgkin lymphoma (HL) is a curable cancer with 10-year survival rates exceeding 80 percent. Treatment for HL has been associated with increased risks for other cancers and cardiovascular diseases, and those later cardiovascular complications may be the consequence of radiotherapy and chemotherapy in HL treatment, according to the study background.

Flora ...

Researchers have developed a large-scale sequencing technique called Genome and Transcriptome Sequencing (G&T-seq) that reveals, simultaneously, the unique genome sequence of a single cell and the activity of genes within that single cell.

The study, published today in Nature Methods, has experimentally established for the first time that when a cell loses or gains a copy of a chromosome during cell division, the genes in that particular region of DNA show decreased or increased expression. While this has long been assumed by genetic researchers, it has not been seen ...

CHESTNUT HILL, MA (April 27, 2015) - Add water to a half-filled cup and the water level rises. This everyday experience reflects a positive material property of the water-cup system. But what if adding more water lowers the water level by deforming the cup? This would mean a negative compressibility.

Now, a quantum version of this phenomenon, called negative electronic compressibility (NEC), has been discovered, a team of researchers led by physicists at Boston College reports today in the online edition of the journal Nature Materials.

Physicists have long theorized ...

Reluctance to share data about personal energy use is likely to be a major obstacle when implementing 'smart' technologies designed to monitor use and support energy efficient behaviours, according to new research led by academics at The University of Nottingham.

The study, published online by the journal Nature Climate Change, found that while more than half of people quizzed would be willing to reduce their personal energy consumption, some were wary about sharing their information with third parties.

Increasing energy efficiency and encouraging flexible energy use ...

April 27, 2015 -- A new breast cancer gene has been identified in a study led by Women's College Hospital (WCH) researcher Dr. Mohammad Akbari, who is also an assistant professor with the Dalla Lana School of Public Health at the University of Toronto. The study, which was published online today in Nature Genetics, describes how mutations in a gene called RECQL are strongly linked to the onset of breast cancer in two populations of Polish and French-Canadian women.

"Our work is an exciting step in identifying all of the relevant genes that are associated with inherited ...

New York, New York -- A multi-year study led by researchers from the Simons Center for Data Analysis (SCDA) and major universities and medical schools has broken substantial new ground, establishing how genes work together within 144 different human tissues and cell types in carrying out those tissues' functions.

The paper, to be published online by Nature Genetics on April 27 (at http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/ng.3259), also demonstrates how computer science and statistical methods may combine to aggregate and analyze very large -- and stunningly diverse -- genomic 'big-data' ...

Researchers at NYU Langone Medical Center have discovered that mitochondria, the major energy source for most cells, also play an important role in stem cell development -- a purpose notably distinct from the tiny organelle's traditional job as the cell's main source of the adenosine triphosphate (ATP) energy needed for routine cell metabolism.

Specifically, the NYU Langone team found that blocking the action of the mitochondrial ATP synthase enzyme stalled egg cell development from stem cells in experiments in fruit flies, one of the main organisms used to study cell ...

An international team of scientists has discovered what amounts to a molecular reset button for our internal body clock. Their findings reveal a potential target to treat a range of disorders, from sleep disturbances to other behavioral, cognitive, and metabolic abnormalities, commonly associated with jet lag, shift work and exposure to light at night, as well as with neuropsychiatric conditions such as depression and autism.

In a study published online April 27 in Nature Neuroscience, the authors, led by researchers at McGill and Concordia universities in Montreal, report ...

Bethesda, MD (April 27, 2015) -- Patients are always interested in understanding what they should eat and how it will impact their health. Physicians are just as interested in advancing their understanding of the major health effects of foods and food-related diseases. To satisfy this need, the editors of Gastroenterology, the official journal of the American Gastroenterological Association, are pleased to announce the publication of this year's highly anticipated special 13th issue on food, the immune system and the gastrointestinal tract.

"This special issue provides ...