(Press-News.org) ANN ARBOR--A new material developed at the University of Michigan stays liquid more than 200 degrees Fahrenheit below its expected freezing point, but a light touch can cause it to form yellow crystals that glow under ultraviolet light.

Even living cells sitting on a film of the supercooled liquid produce crystal footprints, which means that it's about a million times more sensitive than other known molecules that change color in response to pressure.

The material could have applications as a new kind of sensor for living cells, while the mechanism behind its unusual properties may guide the development of electronics and medicines.

"As you know, water freezes around zero degrees Celsius. It changes to ice. It's as if the water remained a liquid down to -100 degrees Celsius," said Kyeongwoon Chung, U-M doctoral student in materials science and engineering and first author on the paper published today in ACS Central Science.

Electronics manufacturers are interested in glass-like, carbon-based materials--known as amorphous, organic materials--like the one produced at U-M. These materials are cheaper, easier to work with and more flexible than inorganic semiconductors such as silicon. Because they don't have a crystal structure that must be broken up, they also dissolve well in the body, which improves their effectiveness as pharmaceuticals.

"We would like to understand better molecular design principles to control the crystallization tendency of organic molecules," said Jinsang Kim, U-M associate professor of materials science and engineering, whose group discovered the unusual molecule. "Most organic materials have a strong driving force to crystallize, but they don't always form the same quality crystal, making quality control difficult."

The team investigated a family of organic molecules widely used in pigments and electronic devices like solar cells, LEDs and transistors looking for ways to streamline the production of their amorphous forms. These molecules can be described as a rigid core flanked by two flexible side chains. If the chains are short, the core molecules drive crystallization, but if they are long, the chains interact to form a different kind of crystal.

The U-M team found that by varying the lengths of the side chains, they could cause a stalemate between two modes of crystallization.

"We found that the core unit and side chains are working in opposite directions," said Kim, who is also an associate professor of chemical engineering, biomedical engineering, macromolecular science and engineering, and chemistry.

As a result, the molecule remained liquid even when cooled below its melting temperature of 273 degrees Fahrenheit. Typically, this would also be the material's freezing point. Instead, the molecules stay in a stable, "supercooled" liquid state down to 41 degrees Fahrenheit, at which point the molecules solidify into a glass.

In addition to the unusually broad temperature range for the supercooled liquid state, the group found that it crystallized when rubbed with a stylus, changing from dark red to bright yellow. The rubbing broke the stalemate between the two ways for the molecules to connect, allowing the side chains to link up.

At high temperatures around 212 degrees Fahrenheit, when the molecules moved freely, just a touch could make the entire film or droplet crystallize.

"It's like a domino effect," Kim said.

But at room temperature, the thicker supercooled liquid crystallized only where the stylus made contact, allowing Chung to scrawl messages such as "shear-triggered crystal" or a secret note to his wife.

Kim's group is pursuing using this molecule in biosensors, which might reveal characteristics of cells for medical diagnosis. The ability to write and erase luminescent information also suggests the potential for use in a memory that encodes information with light rather than magnetism. Such "optical memory" would require much more development.

INFORMATION:

This work was supported in part by the Center for Solar and Thermal Energy Conversion, an Energy Frontier Research Center funded by the U.S. Department of Energy. Additional support came from the Spanish Ministerio de Economia y Competitividad, the Campus of International Excellence and the National Science Foundation.

More than half of patients who report "weekend-only" drug use end up expanding their drug use to weekdays, too -- suggesting that primary care clinicians should monitor patients who acknowledge "recreational" drug use, says a new study by Boston University public health and medicine researchers.

The study, published in the journal Annals of Family Medicine and led by Judith Bernstein, professor of community health sciences at the BU School of Public Health (BUSPH), recommends that clinicians use "caution in accepting recreational drug use as reassuring," and that they ...

People's personalities tend to vary somewhat depending on the season in which they are born, and astrological signs may have developed as a useful system for remembering these patterns, according to an analysis by UConn researcher Mark Hamilton. Such seasonal effects may not be clear in individuals, but can be discerned through averaging personality traits across large cohorts born at the same time of year. Hamilton's analysis will be published in Comprehensive Psychology on 13 May.

Psychologists have known that certain personality traits tend to be associated with certain ...

This news release is available in Japanese.

Pollutants emitted by factories and car exhausts affect humans who breathe in these harmful gases and also aggravate climate change up in the atmosphere. Being able to detect such emissions is a critically needed measure.

New research by the Nanoparticles by Design Unit at the Okinawa Institute of Science and Technology Graduate University (OIST), in collaboration with the Materials Center Leoben Austria and the Austrian Centre for Electron Microscopy and Nanoanalysis has developed an efficient way to improve methods ...

(Boston)--In the largest study to date that examines Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) as a risk factor for cancer, researchers from Boston University School of Medicine (BUSM), have shown no evidence of an association.

The study, which appears in the European Journal of Epidemiology, is consistent with other population-based studies that report stressful life events generally are not associated with cancer incidence. In addition to corroborating results of other studies, this large population sample allowed for important stratified analyses that showed no strong ...

Our bodies' hormones work together to tell us when to eat and when to stop. But for many people who are obese, this system is off-balance. Now scientists have designed a hormone-like compound to suppress hunger and boost satiety, or a full feeling, at the same time. They report in ACS' Journal of Medicinal Chemistry that obese mice given the compound for 14 days had a tendency to eat less than the other groups.

In their study, Constance Chollet and colleagues targeted two main receptors in the body that help keep appetite in check. When hormones bind to ghrelin receptors, ...

WASHINGTON, D.C., May 13, 2015--Policymakers and practitioners have grown increasingly interested in measures of personal qualities other than cognitive ability--including self-control, grit, growth mindset, gratitude, purpose, emotional intelligence, and other beneficial personal qualities--that lead to student success. However, they need to move cautiously before using existing measures to evaluate educators, programs, and policies, or diagnosing children as having "non-cognitive" deficits, according to a review by Angela L. Duckworth and David Scott Yeager published ...

Coffee has gone from dietary foe to friend in recent years, partly due to the revelation that it's rich in antioxidants. Now even spent coffee-grounds are gaining attention for being chock-full of these compounds, which have potential health benefits. In ACS' Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry, researchers explain how to extract antioxidants from the grounds. They then determined just how concentrated the antioxidants are.

María-Paz de Peña and colleagues note that coffee -- one of the most popular drinks in the world -- is a rich source of a group ...

Several class-action lawsuits filed recently against the makers of flushable wet-wipes have brought to light a serious -- and unsavory -- problem: The popular cleaning products might be clogging sewer systems. But whether the manufacturers should be held accountable is still up in the air, according to an article in Chemical & Engineering News (C&EN), the weekly newsmagazine of the American Chemical Society.

Jessica Morrison, assistant editor at C&EN, reports that New York City alone claims to have spent more than $18 million over six years clearing wipes from its wastewater ...

Rats have more heart than you might think. When one is drowning, another will put out a helping paw to rescue its mate. This is especially true for rats that previously had a watery near-death experience, says Nobuya Sato and colleagues of the Kwansei Gakuin University in Japan. Their findings are published in Springer's journal Animal Cognition.

Recent research has shown that a rat will help members of its own species to escape from a tubelike cage. The helping rat will show such prosocial behavior even if it does not gain any advantage from it. To see whether these ...

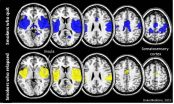

DURHAM, N.C. - Smokers who are able to quit might actually be hard-wired for success, according to a study from Duke Medicine.

The study, published in Neuropsychopharmacology, showed greater connectivity among certain brain regions in people who successfully quit smoking compared to those who tried and failed.

The researchers analyzed MRI scans of 85 people taken one month before they attempted to quit. All participants stopped smoking and the researchers tracked their progress for 10 weeks. Forty-one participants relapsed. Looking back at the brain scans of the 44 ...