(Press-News.org) Washington, DC-- The matter that makes up distant planets and even-more-distant stars exists under extreme pressure and temperature conditions. This matter includes members of a family of seven elements called the noble gases, some of which--such as helium and neon--are household names. New work from a team of scientists led by Carnegie's Alexander Goncharov used laboratory techniques to mimic stellar and planetary conditions, and observe how noble gases behave under these conditions, in order to better understand the atmospheric and internal chemistry of these celestial objects. Their work is published the week of June 15 by Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

The team used a diamond-anvil cell to bring the noble gases helium, neon, argon, and xenon to more than 100,000 times the pressure of Earth's atmosphere (15-52 gigapascals), and used a laser to heat them to temperatures ranging up to 50,000 degrees Fahrenheit (about 28,000 degrees Kelvin).

The gases are called "noble" due to a kind of chemical aloofness; they normally do not combine, or "react," with other elements. Of particular interest were changes in the gases' ability to conduct electricity as the pressure and temperature changed, because this can provide important information about the ways that the noble gases do actually interact with other materials in the extreme conditions of planetary interiors and stellar atmospheres.

Insulators are materials that are unable to conduct the flow of electrons that make up an electric current. Conductors, or metals, are materials that can maintain an electrical current. Nobel gases are not normally conductive at ambient pressures, but conductivity can be induced under higher pressures.

The research team--which included Carnegie's Stewart McWilliams (the lead author), and Douglas Allen Dalton, as well as Mohammad Mahmood of Howard University and Zuzana Konopkova of Deutsches Elektronen-Synchrotron Photon Science in Hamburg, Germany--found that helium, neon, argon, and xenon transform from visually transparent insulators to visually opaque conductors under varying extreme conditions that mimic the interiors of different stars and planets.

This has several exciting implications for how noble gases behave in the atmospheres and interiors of planets and stars.

For example, it could help solve the mystery of why Saturn emits more heat from its interior than would be expected given its stage of formation. This is tied to the ability, or inability, of the noble gases to be dissolved in the liquid hydrogen present in abundance in the interior of gas giant planets such as Saturn and Jupiter.

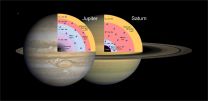

In Jupiter and Saturn, helium would be insulating near the surface and turn metal-like at depths close to both planet's cores. The change from insulator to metal occurs under pressure and temperature conditions at which hydrogen--the main constituent of these planets--is also known to be metallic. It is predicted that helium is, in fact, dissolved in hydrogen under these conditions on both planets and, furthermore, that the miscibility--or ability of two substances to mix--of hydrogen-helium mixtures is correlated with this kind of insulator-to-metal transformation.

However, there was an observed difference in the behavior of neon between the laboratory conditions mimicking the two gas giants. The team's results indicate that neon would remain an insulator even in Saturn's core. As such, an ocean-like envelope of undissolved neon could collect deep within the planet and prevent the erosion of Saturn's core compared to its neighbor Jupiter, where core materials, such as iron, would be dissolving into the surrounding liquid hydrogen.

This lack of core erosion could potentially explain why Saturn is giving off so much internal heat compared to its neighbor Jupiter. Erosion of a planet's core, as in Jupiter, leads to planetary cooling as dense matter is raised upward during mixing, converting heat to gravitational potential energy, whereas in Saturn denser material is allowed to collect at the center of the planet, producing hotter conditions. The fact that Saturn gives off a great deal of internal heat has been a longstanding mystery. These findings could provide the key to solving it.

Another implication of the team's findings involves white dwarf stars, which are the collapsed remnants of once-larger stars, having about the mass of our Sun. They are very compact, but have faint luminosities as they give off residual heat. Dense helium is known to exist in the atmospheres of white dwarf stars and may form the surface atmosphere of some of these celestial bodies. The conditions simulated by the team's laser-heated diamond-anvil cell indicate that this stellar helium should be more opaque (and conducting) than previously expected and this opacity could slow the cooling rates of helium-rich white dwarfs, as well as affect their color.

"Our findings provide yet another example of the vast array of applications for extreme pressure research," Goncharov said. "Further research could reveal so much more about what's going on in the interiors of these objects that are too distant for us to observe more directly."

INFORMATION:

This work was supported by the National Science Foundation Major Research Instrumentation program, the Army Research Office, the Carnegie Institution for Science, the Deep Carbon Observatory Instrumentation grant; the British Council Researcher Links programme; the US Department of Energy NNSA Carnegie/DOE Alliance Center, and the DOE EFRC for Energy Frontier Research in Extreme Environments.

The Carnegie Institution for Science is a private, nonprofit organization headquartered in Washington, D.C., with six research departments throughout the U.S. Since its founding in 1902, the Carnegie Institution has been a pioneering force in basic scientific research. Carnegie scientists are leaders in plant biology, developmental biology, astronomy, materials science, global ecology, and Earth and planetary science.

In a study that twists nature's arm to gain clues into the varied functions of the bacterial genome, North Carolina State University researchers utilize a precision scalpel to excise target genomic regions that are expendable. This strategy can also elucidate gene regions that are essential for bacterial survival. The approach offers a rapid and effective way to identify core and essential genomic regions, eliminate non-essential regions and leads to greater understanding of bacterial evolution in a chaotic pool of gene loss and gene acquisition.

In a paper published ...

This news release is available in Portuguese.

Many animal species, including humans, live and breed in groups with complex social organizations. The impact of this social structure on the genetic diversity of animals has been a source of disagreement between scientists. In a new study now published in the latest edition of the scientific journal PNAS*, Barbara Parreira and Lounes Chikhi from Instituto Gulbenkian de Ciencia (IGC; Portugal) show that social structure is important to maintain the genetic diversity within species. The researchers provide a new mathematical ...

Belonging to multiple groups that are important to you boosts self-esteem much more than having friends alone, new research has found.

CIFAR fellows Nyla Branscombe (University of Kansas), Alexander Haslam and Catherine Haslam (both University of Queensland) recently collaborated with lead author Jolanda Jetten on experiments to explore the importance of group memberships for self-esteem. Working with groups of school children, the elderly, and former homeless people in the United Kingdom, China and Australia, their studies showed consistently that people who belong ...

The environmental movement is making a difference - nudging greenhouse gas emissions down in states with strong green voices, according to a Michigan State University (MSU) study.

Social scientist Thomas Dietz and Kenneth Frank, MSU Foundation professor of sociometrics, have teamed up to find a way to tell if a state jumping on the environmental bandwagon can mitigate other human factors - population growth and economic affluence - known to hurt the environment.

"We've used new methods developed over the years and new innovations Ken has developed to add in the politics ...

Using Twitter and Google search trend data in the wake of the very limited U.S. Ebola outbreak of October 2014, a team of researchers from Arizona State University, Purdue University and Oregon State University have found that news media is extraordinarily effective in creating public panic.

Because only five people were ultimately infected yet Ebola dominated the U.S. media in the weeks after the first imported case, the researchers set out to determine mass media's impact on people's behavior on social media.

"Social media data have been suggested as a way to track ...

Vitamin D plays an important part in the human immune response and deficiency can leave individuals less able to fight infections like HIV-1. Now an international team of researchers has found that high-dose vitamin D supplementation can reverse the deficiency and also improve immune response.

"Vitamin D may be a simple, cost-effective intervention, particularly in resource-poor settings, to reduce HIV-1 risk and disease progression," the researchers report in today's (June 15) online issue of Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

The researchers looked at ...

MAYWOOD, IL - Poverty is known to be a strong risk factor for end-stage kidney disease. Now, a first of-its-kind study has found that the association between poverty and kidney disease changes over time.

The percentage of adults beginning kidney dialysis who lived in zip codes with high poverty rates increased from 27.4 percent during the 1995-2004 time period to 34 percent in 2005-2010.

The study, by corresponding author Holly Kramer, MD, MPH and colleagues at Loyola University Chicago Stritch School of Medicine, is published in the journal Hemodialysis International.

Researchers ...

For the last decade, astronomers have observed curious "hotspots" on Saturn's poles. In 2008, NASA's Cassini spacecraft beamed back close-up images of these hotspots, revealing them to be immense cyclones, each as wide as the Earth. Scientists estimate that Saturn's cyclones may whip up 300 mph winds, and likely have been churning for years.

While cyclones on Earth are fueled by the heat and moisture of the oceans, no such bodies of water exist on Saturn. What, then, could be causing such powerful, long-lasting storms?

In a paper published today in the journal Nature ...

New research by NOAA, University of Alaska, and Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution in the journal Oceanography shows that surface waters of the Chukchi and Beaufort seas could reach levels of acidity that threaten the ability of animals to build and maintain their shells by 2030, with the Bering Sea reaching this level of acidity by 2044.

"Our research shows that within 15 years, the chemistry of these waters may no longer be saturated with enough calcium carbonate for a number of animals from tiny sea snails to Alaska King crabs to construct and maintain their shells ...

AUSTIN, Texas -- Researchers in the Cockrell School of Engineering at The University of Texas at Austin have developed a groundbreaking new energy-absorbing structure to better withstand blunt and ballistic impact. The technology, called negative stiffness (NS) honeycombs, can be integrated into car bumpers, military and athletic helmets and other protective hardware.

The technology could have major implications for the design and production of future vehicles and military gear to improve safety.

The new NS honeycomb structures are able to provide repeated protection ...