Salk Institute and Sanford Burnham Prebys Medical Discovery Institute (SBP) scientists have developed a drug that prevents this process from starting in cancer cells. Published June 25, 2015 in Molecular Cell, the new study identifies a small molecule drug that specifically blocked the first step of autophagy, effectively cutting off the recycled nutrients that cancer cells need to live.

"The finding opens the door to a new way to attack cancer," says Reuben Shaw, a senior author of the paper, professor in the Molecular and Cell Biology Laboratory at the Salk Institute and a Howard Hughes Medical Institute Early Career Scientist. "The inhibitor will probably find the greatest utility in combination with targeted therapies."

Besides cancer, defects in autophagy have been linked with infectious diseases, neurodegeneration and heart problems. In a 2011 study in the journal Science, Shaw and his team discovered how cells starved of nutrients activate the key molecule that kicks off autophagy, an enzyme called ULK1.

Reasoning that inhibiting ULK1 might snuff out some types of cancer by stifling a main energy supply that comes from the recycling process, Shaw's group and others wanted to find a drug that would inhibit the enzyme. Only a fraction of such inhibitors that show promise in a test tube end up working well in living cells. Shaw's group spent more than a year studying how ULK1 works and developing new strategies for screening its function in cells.

A key breakthrough came when Shaw met the paper's other senior author, Nicholas Cosford, a professor in the NCI-Designated Cancer Center at SBP. Cosford had been investigating ULK1 using medicinal chemistry and chemical biology, and had identified some promising lead compounds using rational design. The two labs combined efforts to screen hundreds of potential molecules for ULK1 inhibition, narrowing the list down to a few dozen, and eventually one.

"The key to success for this project came when we combined Reuben's deep understanding of the fundamental biology of autophagy with our chemical expertise," says Cosford. "This allowed us to find a drug that targeted ULK1 not just in a test tube but also in tumor cells. Another challenge was finding molecules that selectively targeted the ULK1 enzyme without affecting healthy cells. Our work provides the basis for a novel drug that will treat resistant cancer by cutting off a main tumor cell survival process."

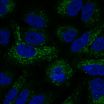

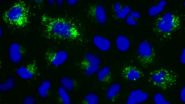

The result was a highly selective drug they named SBI-0206965, which successfully killed a number of cancer cell types, including human and mouse lung cancer cells and human brain cancer cells, some of which were previously shown to be particularly reliant on cellular recycling.

Interestingly, some cancer drugs (such as mTOR inhibitors) further activate cell recycling by shutting off the ability of those cells to take up nutrients, making them more reliant on recycling to provide all the building blocks cells need to stay alive. Rapamycin, for example, works by shutting down cell growth and division. In response, the cells launch into recycling mode by turning on ULK1, which may be one reason why, rather than dying, some cancer cells seem to go into a dormant state and return--often more drug resistant--after treatment stops.

"Inhibiting ULK1 would eliminate this last-ditch survival mechanism in the cancer cells and could make existing anti-cancer treatments much more effective," says Matthew Chun, one of the study's lead authors and a postdoctoral fellow in the Shaw lab at Salk.

Indeed, combining SBI-0206965 with mTOR inhibitors made it more effective, killing two to three times as many lung cancer cells as SBI-0206965 alone or the mTOR inhibitors alone.

Drugging the autophagy pathway to combat cancer has been tried before, but the only drugs that currently block cell recycling work by targeting the cell organelle known as the lysosome, which functions at the final stage of autophagy. Although these lysosomal therapies are being tested in early-stage clinical trials, they inhibit other lysosomal functions beyond autophagy, and therefore may have additional side effects.

Comparing equivalent concentrations of the lysosomal drug chloroquine with SBI-0206965, in combination mTOR inhibitors, the scientists found that SBI-0206965 was better than chloroquine at killing cancer cells.

The group is now testing the drug in mouse models of cancer. "An important next step will be testing this drug in other types of cancer and with other therapeutic combinations," says Shaw, who is deputy director of Salk's NCI-Designated Cancer Center. "In the meantime, this discovery gives researchers an exciting new toolbox for the inhibition and measurement of cell recycling."

INFORMATION:

Other authors on the study include co-lead author Daniel Egan of Salk's Molecular and Cell Biology Laboratory; Mitchell Vamos, Haixia Zou, Juan Rong, Dhanya Raveendra-Panickar, Douglas Sheffler, and Peter Teriete of the Cell Death and Survival Networks Research Program in the NCI-Designated Cancer Center at SBP; Chad Miller, Hua Jane Lou, and Benjamin Turk of the Department of Pharmacology in Yale University School of Medicine; John Asara of the Division of Signal Transduction in Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center and the Department of Medicine in Harvard Medical School; and Chih-Cheng Yang of SBP's Functional Genomics Core.

The research was supported by National Institutes of Health, the Department of Defense, and the Leona M. and Harry B. Helmsley Charitable Trust.

About the Salk Institute for Biological Studies:

The Salk Institute for Biological Studies is one of the world's preeminent basic research institutions, where internationally renowned faculty probes fundamental life science questions in a unique, collaborative and creative environment. Focused both on discovery and on mentoring future generations of researchers, Salk scientists make groundbreaking contributions to our understanding of cancer, aging, Alzheimer's, diabetes and infectious diseases by studying neuroscience, genetics, cell and plant biology, and related disciplines.

Faculty achievements have been recognized with numerous honors, including Nobel Prizes and memberships in the National Academy of Sciences. Founded in 1960 by polio vaccine pioneer Jonas Salk, MD, the Institute is an independent nonprofit organization and architectural landmark.

About Sanford Burnham Prebys Medical Discovery Institute

Sanford Burnham Prebys Medical Discovery Institute (SBP) is an independent nonprofit research organization that blends cutting-edge fundamental research with robust drug discovery to address unmet clinical needs in the areas of cancer, neuroscience, immunity, and metabolic disorders. The Institute invests in talent, technology, and partnerships to accelerate the translation of laboratory discoveries that will have the greatest impact on patients. Recognized for its world-class NCI-designated Cancer Center and the Conrad Prebys Center for Chemical Genomics, SBP employs more than 1,100 scientists and staff in San Diego (La Jolla), Calif., and Orlando (Lake Nona), Fla. For more information, visit us at SBPdiscovery.org. The Institute can also be found on Facebook at facebook.com/SBPdiscovery and on Twitter @SBPdiscovery.