(Press-News.org) PITTSBURGH, June 18, 2015 - Researchers at the University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine have devised a computational model that could enhance understanding, diagnosis and treatment of pressure ulcers related to spinal cord injury. In a report published online in PLOS Computational Biology, the team also described results of virtual clinical trials that showed that for effective treatment of the lesions, anti-inflammatory measures had to be applied well before the earliest clinical signs of ulcer formation.

Pressure ulcers affect more than 2.5 million Americans annually and patients who have spinal cord injuries that impair movement are more vulnerable to developing them, said senior investigator Yoram Vodovotz, Ph.D., professor of surgery and director of the Center for Inflammation and Regenerative Modeling at the Pitt School of Medicine.

"These lesions are thought to develop because immobility disrupts adequate oxygenation of tissues where the patient is lying down, followed by sudden resumption of blood flow when the patient is turned in bed to change positions," Dr. Vodovotz said. "This is accompanied by an inflammatory response that sometimes leads to further tissue damage and breakdown of the skin."

"Pressure ulcers are an unfortunately common complication after spinal cord injury and cause discomfort and functional limitations," said co-author Gwendolyn A. Sowa, M.D., Ph.D., associate professor of physical medicine and rehabilitation, Pitt School of Medicine. "Improving the individual diagnosis and treatment of pressure ulcers has the potential to reduce the cost of care and improve quality of life for persons living with spinal cord injury."

To address the complexity of the biologic pathways that create and respond to pressure sore development, the researchers designed a computational, or "in silico," model of the process based on serial photographs of developing ulcers from spinal cord-injured patients enrolled in studies at Pitt's Rehabilitation Engineering Research Center on Spinal Cord Injury. Photos were taken when the ulcer was initially diagnosed, three times per week in the acute stage and once a week as it resolved.

Then they validated the model, finding that if they started with a single small round area over a virtual bony protuberance and altered factors such as inflammatory mediators and tissue oxygenation, they could recreate a variety of irregularly shaped ulcers that mimic what is seen in reality.

They also conducted two virtual trials of potential interventions, finding that anti-inflammatory interventions could not prevent ulcers unless applied very early in their development.

In the future, perhaps a nurse or caregiver could simply send in a photo of a patient's reddened skin to a doctor using the model to find out whether it was likely to develop into a pressure sore for quick and aggressive treatment to keep it from getting far worse, Dr. Vodovotz speculated.

"Computational models like this one might one day be able to predict the clinical course of a disease or injury, as well as make it possible to do less expensive testing of experimental drugs and interventions to see whether they are worth pursuing with human trials," he said. "They hold great potential as a diagnostic and research tool."

INFORMATION:

The team included co-senior author Gary An, M.D., of the University of Chicago; Cordelia Ziraldo, Ph.D., Alexey Solovyev, Ph.D., Ana Allegretti, Ph.D., Shilpa Krishnan, M.S., David Brienza, Ph.D., Qi Mi, Ph.D., all of Pitt; and M. Kristi Henzel, M.D., Ph.D., of the Louis Stokes Cleveland Veterans Affairs Medical Center.

The project was funded by the U.S. Department of Education; National Institutes of Health National Institute on Disability and Rehabilitation Research grant H133E070024; and an IBM Shared University Research Award.

About the University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine

As one of the nation's leading academic centers for biomedical research, the University of Pittsburgh School Of Medicine integrates advanced technology with basic science across a broad range of disciplines in a continuous quest to harness the power of new knowledge and improve the human condition. Driven mainly by the School of Medicine and its affiliates, Pitt has ranked among the top 10 recipients of funding from the National Institutes of Health since 1998. In rankings recently released by the National Science Foundation, Pitt ranked fifth among all American universities in total federal science and engineering research and development support.

Likewise, the School of Medicine is equally committed to advancing the quality and strength of its medical and graduate education programs, for which it is recognized as an innovative leader, and to training highly skilled, compassionate clinicians and creative scientists well-equipped to engage in world-class research. The School of Medicine is the academic partner of UPMC, which has collaborated with the University to raise the standard of medical excellence in Pittsburgh and to position health care as a driving force behind the region's economy. For more information about the School of Medicine, see http://www.medschool.pitt.edu.

http://www.upmc.com/media

Contact: Anita Srikameswaran

Phone: 412-578-9193

E-mail: SrikamAV@upmc.edu

Contact: Rick Pietzak

Phone: 412-864-4151

E-mail: PietzakR@upmc.edu

Chloroplasts, better known for taking care of photosynthesis in plant cells, play an unexpected role in responding to infections in plants, researchers at UC Davis and the University of Delaware have found.

When plant cells are infected with pathogens, networks of tiny tubes called stromules extend from the chloroplasts and make contact with the cell's nucleus, the team discovered. The tubes likely deliver signals from the chloroplast to the nucleus that induce programmed cell death of infected cells and prepare other cells to resist infection. The work is published online ...

Magnolias are prized for their large, colorful, fragrant flowers. Does the attractive, showy tree also harbor a potent cancer fighter?

Yes, according to a growing number of studies, including one from VA and the University of Alabama at Birmingham that is now online in the journal Oncotarget.

The study focused on squamous cell head and neck cancers, a scourge among those who use tobacco and alcohol. According to the National Cancer Institute, at least 3 in 4 head and neck cancers are caused by the use of tobacco and alcohol. The cancers have only a 50 percent survival ...

Without new conservation efforts, the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) could lose up to 20 percent of its forests, unleashing a 60 percent increase in carbon emissions, says a new study by researchers at the University of Vermont's Gund Institute for Ecological Economics.

Published by PLOS ONE, the study explores Central Africa's tropical forests, which are among the world's largest carbon reserves. While these forests have historically experienced low deforestation rates, pressures to clear land are growing due to development, foreign investment in agriculture, and ...

An international group of academic leaders, journal editors and funding-agency representatives and disciplinary leaders, including Rick Wilson, the Herbert S. Autrey Chair of Political Science and professor of statistics and psychology at Rice University, has announced guidelines to further strengthen transparency and reproducibility practices in science research reporting.

The group, the Transparency and Openness Promotion (TOP) Committee at the Center for Open Science in Charlottesville, Va., outlined its new guidelines in a story published in this week's edition of ...

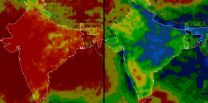

Rainwater could save people in India a bucket of money, according to a new study by scientists looking at NASA satellite data.

The study, partially funded by NASA's Precipitation Measurement Missions, found that collecting rainwater for vegetable irrigation could reduce water bills, increase caloric intake and even provide a second source of income for people in India.

The study, published in the June issue of Urban Water Journal, is based on precipitation data from the Tropical Rainfall Measuring Mission (TRMM), a joint mission between NASA and the Japan Aerospace ...

The majority of the United States' poor aren't sitting on street corners. They're employed at low-paying jobs, struggling to support themselves and a family.

In the past, differing definitions of employment and poverty prevented researchers from agreeing on who and how many constitute the "working poor."

But a new study by sociologists at BYU, Cornell and LSU provides a rigorous new estimate. Their work suggests about 10 percent of working households are poor. Additionally, households led by women, minorities or individuals with low education are more likely to be ...

A new study led by researchers at Scripps Institution of Oceanography at UC San Diego indicates a steady population trend for blue whales and an upward population trend for fin whales in Southern California.

Scripps marine acoustician Ana Širović and her colleagues in the Marine Bioacoustics Lab and Scripps Whale Acoustic Lab intermittently deployed 16 High-frequency Acoustic Recording Packages (HARPs)--devices that sit on the seafloor with a suspended hydrophone (an underwater microphone)--to collect acoustic data on whales off Southern California from 2006-2012. ...

MINNEAPOLIS - A new study suggests that errors on memory and thinking tests may signal Alzheimer's up to 18 years before the disease can be diagnosed. The research is published in the June 24, 2015, online issue of Neurology®, the medical journal of the American Academy of Neurology.

"The changes in thinking and memory that precede obvious symptoms of Alzheimer's disease begin decades before," said study author Kumar B. Rajan, PhD, with Rush University Medical Center in Chicago. "While we cannot currently detect such changes in individuals at risk, we were able to ...

"Hydraulic fracturing" (or fracking) and "environmentally friendly" often do not appear in the same sentence together. But as the United States teeters on the precipice of a shale gas boom, Northwestern University professor Fengqi You is exploring ways to make the controversial activity easier on the environment -- and the wallet.

"Shale gas is promising," said You, assistant professor of chemical and biological engineering at Northwestern's McCormick School of Engineering and Applied Science. "No matter if you like it or not, it's already out there. The question we want ...

Over 50 leading doctors and academics including Fiona Godlee, editor in chief of The BMJ, have signed an open letter published in The Guardian today calling on the Wellcome Trust to divest from fossil fuel companies.

The letter is part of The Guardian's "Keep it in the Ground" Campaign that is urging the world's two biggest charitable funds -- the Wellcome Trust and the Gates Foundation -- to move their money out of fossil fuels.

It reads: "Divestment rests on the premise that it is wrong to profit from an industry whose core business threatens human and planetary health, ...