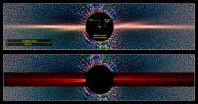

(Press-News.org) A new NASA supercomputer simulation of the planet and debris disk around the nearby star Beta Pictoris reveals that the planet's motion drives spiral waves throughout the disk, a phenomenon that causes collisions among the orbiting debris. Patterns in the collisions and the resulting dust appear to account for many observed features that previous research has been unable to fully explain.

"We essentially created a virtual Beta Pictoris in the computer and watched it evolve over millions of years," said Erika Nesvold, an astrophysicist at the University of Maryland, Baltimore County, who co-developed the simulation. "This is the first full 3-D model of a debris disk where we can watch the development of asymmetric features formed by planets, like warps and eccentric rings, and also track collisions among the particles at the same time."

In 1984, Beta Pictoris became the second star known to be surrounded by a bright disk of dust and debris. Located only 63 light-years away, Beta Pictoris is an estimated 21 million years old, or less than 1 percent the age of our solar system. It offers astronomers a front-row seat to the evolution of a young planetary system and it remains one of the closest, youngest and best-studied examples today. The disk, which we see edge on, contains rock and ice fragments ranging in size from objects larger than houses to grains as small as smoke particles. It's a younger version of the Kuiper belt at the fringes of our own planetary system.

Nesvold and her colleague Marc Kuchner, an astrophysicist at NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Md., presented the findings Thursday during the "In the Spirit of Lyot 2015" conference in Montreal, which focuses on the direct detection of planets and disks around distant stars. A paper describing the research has been submitted to The Astrophysical Journal.

In 2009, astronomers confirmed the existence of Beta Pictoris b, a planet with an estimated mass of about nine times Jupiter's, in the debris disk around Beta Pictoris. Traveling along a tilted and slightly elongated 20-year orbit, the planet stays about as far away from its star as Saturn does from our sun.

Astronomers have struggled to explain various features seen in the disk, including a warp apparent at submillimeter wavelengths, an X-shaped pattern visible in scattered light, and vast clumps of carbon monoxide gas. A common ingredient in comets, carbon monoxide molecules are destroyed by ultraviolet starlight in a few hundred years. To explain why the gas is clumped, previous researchers suggested the clumps could be evidence of icy debris being corralled by a second as-yet-unseen planet, resulting in an unusually high number of collisions that produce carbon monoxide. Or perhaps the gas was the aftermath of an extraordinary crash of icy worlds as large as Mars.

"Our simulation suggests many of these features can be readily explained by a pair of colliding spiral waves excited in the disk by the motion and gravity of Beta Pictoris b," Kuchner said. "Much like someone doing a cannonball in a swimming pool, the planet drove huge changes in the debris disk once it reached its present orbit."

Keeping tabs on thousands of fragmenting particles over millions of years is a computationally difficult task. Existing models either weren't stable over a sufficiently long time or contained approximations that could mask some of the structure Nesvold and Kuchner were looking for.

Working with Margaret Pan and Hanno Rein, both now at the University of Toronto, they developed a method where each particle in the simulation represents a cluster of bodies with a range of sizes and similar motions. By tracking how these "superparticles" interact, they could see how collisions among trillions of fragments produce dust and, combined with other forces in the disk, shape it into the kinds of patterns seen by telescopes. The technique, called the Superparticle-Method Algorithm for Collisions in Kuiper belts (SMACK), also greatly reduces the time required to run such a complex computation.

Using the Discover supercomputer operated by the NASA Center for Climate Simulation at Goddard, the SMACK-driven Beta Pictoris model ran for 11 days and tracked the evolution of 100,000 superparticles over the lifetime of the disk.

As the planet moves along its tilted path, it passes vertically through the disk twice each orbit. Its gravity excites a vertical spiral wave in the disk. Debris concentrates in the crests and troughs of the waves and collides most often there, which explains the X-shaped pattern seen in the dust and may help explain the carbon monoxide clumps.

The planet's orbit also is slightly eccentric, which means its distance from the star varies a little every orbit. This motion stirs up the debris and drives a second spiral wave across the face of the disk. This wave increases collisions in the inner regions of the disk, which removes larger fragments by grinding them away. In the real disk, astronomers report a similar clearing out of large debris close to the star.

"One of the nagging questions about Beta Pictoris is how the planet ended up in such an odd orbit," Nesvold explained. "Our simulation suggests it arrived there about 10 million years ago, possibly after interacting with other planets orbiting the star that we haven't detected yet."

INFORMATION:

Chronic disease and mental health issues disproportionately affect low-income African-Americans, Latinos and Hispanics, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Two new studies by the UCLA Center for Culture, Trauma and Mental Health Disparities shed light on the causes and impacts of this disparity.

The first study, published online by the journal Psychological Trauma, analyzed certain types of negative experiences that may affect low-income African-Americans and Latinos. It found five specific environmental factors, which the researchers call "domains," ...

Every time you put on bug spray this summer, you're launching a strike in the ongoing war between humans and mosquitoes -- one that is rapidly driving the evolution of the pests.

Scientists studying mosquitoes in various types of environments in the United States and in Russia found that between 5 and 20 percent of a mosquito population's genome is subject to evolutionary pressures at any given time -- creating a strong signature of local adaptation to environment and humans.

This means that individual populations are likely to have evolved resistance to whatever local ...

Tens of millions of Americans -- an estimated 1 to 2 percent of the population -- will suffer at some point in their lifetimes from obsessive-compulsive disorder, a disorder characterized by recurrent, intrusive, and disturbing thoughts (obsessions), and/or stereotyped recurrent behaviors (compulsions). Left untreated, OCD can be profoundly distressing to the patient and can adversely affect their ability to succeed in school, hold a job or function in society.

One of the most common and effective treatments is cognitive-behavioral therapy, which aims to help patients ...

URBANA, Ill. -- When children participated in a program designed to reduce sibling conflict, both parents benefited from a lessening of hostilities on the home front. But mothers experienced a more direct reward. As they viewed the children's sessions in real time on a video monitor and coached the kids at home to respond as they'd been taught, moms found that, like their kids, they were better able to manage their own emotions during stressful moments.

"Parenting more than one child is stressful, and until now, there have been few ways to help parents deal with their ...

In a paper that crystalizes knowledge from a variety of experiments and theoretical developments, scientists from the RIKEN Center for Emergent Matter Science in Japan have demonstrated that the quantum spin Hall effect--an effect known to take place in solid state physics--is also an intrinsic property of light.

Photons have neither mass nor charge, and so behave very differently from their massive counterparts, but they do share a property, called spin, which results in remarkable geometric and topological phenomena. The spin--a measure of the intrinsic angular momentum--can ...

Pressure ulcers affect more than 2.5 million Americans annually and patients who have spinal cord injuries that impair movement are more vulnerable to ulcer development. Researchers at the University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine have devised a computational model that could enhance understanding, diagnosis and treatment of pressure ulcers related to spinal cord injury. The research publishing this week in PLOS Computational Biology, shows the results of virtual clinical trials that demonstrated that in order to effectively treat the lesions, anti-inflammatory measures ...

Antibiotic resistance, and multi-drug resistance, is a major public health threat. A new study publishing in PLOS Computational Biology finds conditions where restricting certain antibiotics may increase the frequency of multiple drug resistance.

Uri Obolski and Prof. Lilach Hadany and colleagues used a mathematical model and electronic medical records data to show that drug restriction may also lead to results opposite of those desired. Restriction might facilitate the spread of resistant pathogens, due to ineffective treatment with antibiotics that have high resistance ...

This news release is available in Japanese.

Researchers studying poppy plants -- the natural source of pain-relieving alkaloids, such as morphine and codeine -- have identified a fusion gene that facilitates important, back-to-back steps in the plant's morphine-producing pathway. These findings, which build upon recent efforts to engineer the morphine biosynthesis pathway in yeast, complete the metabolic pathway for morphine and pave the way for cheaper, safer routes to producing the economically important drug without the need for cultivating poppy fields. For about ...

This news release is available in Japanese.

Researchers have figured out a way to pump more light farther along an optical fiber, offering engineers a potential solution to the so-called "capacity crunch" that threatens to limit bandwidth on the Web. These findings, which represent a step toward a faster and vaster Internet, show that silica fibers -- the hair-like wires that form the basis of fiber-optic communication -- can handle a lot more data than researchers had originally estimated. Normally, information traveling through an optical fiber is subject to nonlinear ...

The relentless flow of a glacier may seem unstoppable, but a team of UK and US researchers have shown that during some calving events - when an iceberg breaks off into the ocean - the glacier moves rapidly backward and downward, causing the characteristic glacial earthquakes which until now have been poorly understood.

This new insight into glacier behaviour should enable scientists to measure glacier calving remotely and will improve the reliability of models that predict future sea-level rise in a warming climate.

The research is published today in Science Express. ...