(Press-News.org) Spider-like cells inside the brain, spinal cord and eye hunt for invaders, capturing and then devouring them. These cells, called microglia, often play a beneficial role by helping to clear trash and protect the central nervous system against infection. But a new study by researchers at the National Eye Institute (NEI) shows that they also accelerate damage wrought by blinding eye disorders, such as retinitis pigmentosa. NEI is part of the National Institutes of Health.

"These findings are important because they suggest that microglia may provide a target for entirely new therapeutic strategies aimed at halting blinding eye diseases of the retina," said NEI Director, Paul A. Sieving, M.D. "New targets create untapped opportunities for preventing disease-related damage to the eye, and preserving vision for as long as possible." The findings were published in the journal EMBO Molecular Medicine.

Retinitis pigmentosa, an inherited disorder that affects roughly 1 in 4,000 people, damages the retina, the light-sensitive tissue at the back of the eye. Research has shown links between retinitis pigmentosa and several mutations in genes for photoreceptors, the cells in the retina that convert light into electrical signals that are sent to the brain via the optic nerve. In the early stages of the disease, rod photoreceptors, which enable us to see in low light, are lost, causing night blindness. As the disease progresses, cone photoreceptors, which are needed for sharp vision and seeing colors, can also die off, eventually leading to complete blindness.

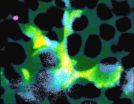

Lead investigator, Wai T. Wong M.D., Ph.D., chief of the Unit on Neuron-Glia Interactions in Retinal Disease at NEI, and his team studied mice with a mutation in a gene that can also cause retinitis pigmentosa in people. The researchers observed in these mice that very early in the disease process, the microglia infiltrate a layer of the retina near the photoreceptors, called the outer nuclear layer, where they don't usually venture. The microglia then create a cup-like structure over a single photoreceptor, surrounding it to ingest it in a process called phagocytosis. Wong and his team caught this dynamic process on video. The whole feast, including digestion, takes about an hour.

Phagocytosis is a normal process in healthy tissues and is a key way of clearing away dead cells and cellular debris. However, in retinitis pigmentosa the researchers found that the microglia target damaged but living photoreceptors, in addition to dead ones. To confirm that microglia contribute to the degeneration process, the researchers genetically eliminated the microglia, which slowed the rate of rod photoreceptor death and the loss of visual function in the mice. Inhibiting phagocytosis with a compound had a similar effect. The microglia seem to ignore cone photoreceptors, which fits with the known early course of retinitis pigmentosa.

"These findings suggest that therapeutic strategies that inhibit microglial activation may help decelerate the rate of rod photoreceptor degeneration and preserve vision," Wong said.

What triggers microglia to go on this destructive feeding frenzy? Wong and colleagues found evidence that photoreceptors carrying mutations undergo physiological stress. The stress then triggers them to secrete chemicals dubbed "find me" signals, which is like ringing a dinner bell that attracts microglia into the retinal layer. Once there, the microglia probe the photoreceptors repeatedly, exposing themselves to "eat me" signals, which then trigger phagocytosis. In response to all the feasting, the microglia become activated. That is, they send out their own signals to call other microglia to the scene and they release substances that promote inflammation.

Other potential treatments for retinitis pigmentosa, such as gene therapy, are progressing, but are not without challenges. Gene therapy requires replacing defective genes with functional genes, yet more than 50 distinct genes have been linked to the disease in different families, so there's no one-size-fits-all gene therapy. A therapy targeting microglia might complement gene therapy because it's an approach that's independent of the specific genetic cause of retinitis pigmentosa, said Wong.

INFORMATION:

A clinical trial (NCT02140164) is already underway at NEI to see if the anti-inflammatory drug minocycline can block the activation of microglia and help slow the progression of retinitis pigmentosa. The trial is currently recruiting participants. For more information, see https://www.clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02140164.

Wong's lab colleagues Lian Zhao, Ph.D., Matthew Zabel, Ph.D., and Xu Wang, M.D., Ph.D., played key roles in conceiving and conducting this research. To hear Zabel talk about his work on retinitis pigmentosa, watch this video from NIH and LabTV.

To watch a video of microglia eating rod photoreceptors, go to http://youtu.be/xXmUGYCi7rE.

This research was supported by the National Eye Institute Intramural Research Program and grant NS087198 from NIH's National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke.

References:

Zhao L, Zabel MK, Wang X et al. "Microglial phagocytosis of living photoreceptors contributes to inherited retinal Degeneration." EMBO Mol Med, July 2. DOI: 10.15252/emmm.201505298

NEI leads the federal government's research on the visual system and eye diseases. NEI supports basic and clinical science programs that result in the development of sight-saving treatments. For more information, visit http://www.nei.nih.gov.

About the National Institutes of Health (NIH): NIH, the nation's medical research agency, includes 27 Institutes and Centers and is a component of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. NIH is the primary federal agency conducting and supporting basic, clinical, and translational medical research, and is investigating the causes, treatments, and cures for both common and rare diseases. For more information about NIH and its programs, visit http://www.nih.gov.

NIH...Turning Discovery Into Health®

A new method for calculating the exact time of death, even after as much as 10 days, has been developed by a group of researchers at the University of Salzburg.

Currently, there are no reliable ways to determine the time since death after approximately 36 hours. Initial results suggest that this method can be applied in forensics to estimate the time elapsed since death in humans.

By observing how muscle proteins and enzymes degrade in pigs, scientists at the University of Salzburg have developed a new way of estimating time since death that functions up to at least ...

When remembering something from our past, we often vividly re-experience the whole episode in which it occurred. New UCL research funded by the Medical Research Council and Wellcome Trust has now revealed how this might happen in the brain.

The study, published in Nature Communications, shows that when someone tries to remember one aspect of an event, such as who they met yesterday, the representation of the entire event can be reactivated in the brain, including incidental information such as where they were and what they did.

"When we recall a previous life event, ...

Classical Brownian motion theory was established over one hundred year ago, describing the stochastic collision behaviors between surrounding molecules. Recently, researchers from Technical Institute of Physics and Chemistry, Chinese Academy of Sciences discovered that the self-powered liquid metal motors in millimeter scale demonstrated similar Brownian like motion behaviors in alkaline solution. And the force comes from the hydrogen gas stream generated at the interface between liquid metal motor and its contacting substrate bottom.

Ever since the irregular motions ...

A group of the world's top doctors and scientists working in cardiology and preventive medicine have issued a call to action to tackle the global problem of deaths from non-communicable diseases (NCDs), such as heart problems, diabetes and cancer, through healthy lifestyle initiatives.

They say that identifying the enormous burden caused by NCDs is not enough and it is time for "all hands on deck" to pursue strategies both within and outside traditional healthcare systems that will succeed in promoting healthier lifestyles in order to prevent or delay health conditions ...

Sophia Antipolis, 02 July 2015: Patients are experiencing significant delays in access to approved cardiovascular devices due to bureaucratic inefficiencies, reveals a Devices White Paper from the Cardiovascular Round Table (CRT) published today in European Heart Journal.1

There is a clear correlation between declining death rates from cardiovascular disease and the introduction of innovative techniques and devices.1

The CRT is an independent forum established by the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and comprised of cardiologists and representatives of the pharmaceutical, ...

Birds that moult at the wrong time of the year could be disadvantaged, according to a study by scientists at Lund University, Sweden. Birds depend on a full set of feathers for maximum efficiency when flying long distances, but the study shows that moulting has a detrimental effect on their flight performance.

The researchers trained a jackdaw to fly in a wind tunnel and measured different types of drag experienced by the bird. "We expected the bird not to be able to glide at the lowest speeds that it could glide at before moult and our results confirmed this", says ...

Children with Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) may be successfully supported in classrooms through strategies that do not involve drugs, new research has indicated. These children are typically restless, act without thinking and struggle to concentrate, which causes particular problems for them and for others in school.

A systematic review was led by the University of Exeter Medical School funded by NIHR's Health Research Technology Assessment programme and supported by the NIHR Collaboration for Leadership in Applied Health Research and Care South West ...

Being able to dive is what matters most for seal pups, but how do they learn to do it? Grey seal pups that can play in pools may have better diving skills once they make the move to the sea, and this could increase their chance of survival. Researchers at Plymouth University have found that spending time in pools of water helps seal pups hold their breath for longer.

Many seal species stay on land after they have weaned before they go to sea to feed for the first time. "It is during this period of fasting that access to water can make a difference to diving ability," ...

New guidelines for diagnosing chronic lung disease (chronic obstructive pulmonary disease or COPD), should be modified because they over-diagnose COPD in older men and under-diagnose COPD in young women.

Writing in The BMJ this week, Professor Martin Miller and Dr Mark Levy say up to 13% of people thought to have COPD under the new criteria have been found to be misdiagnosed.

They argue that clinicians should use internationally agreed standards when assessing patients for COPD. This, they say, will help to improve patient care through more accurate diagnosis, as well ...

Evidence is lacking that having a category of drugs that can be sold only by pharmacists or under their supervision ("pharmacy medicines") has benefits, writes a pharmacy professor in The BMJ this week.

Professor Paul Rutter at the School of Pharmacy, University of Wolverhampton, calls for an end to pharmacists' monopoly on selling some drugs and thinks that a two tier system of prescription or non-prescription drugs, like in the US, would be simpler.

He mentions the recent case of the painkiller, oral diclofenac, that used to be available as a non-prescription drug ...