(Press-News.org) NEW YORK, NY (July 2, 2015)--Research from Eric Kandel's lab at Columbia University Medical Center (CUMC) has uncovered further evidence of a system in the brain that persistently maintains memories for long periods of time. And paradoxically, it works in the same way as mechanisms that cause mad cow disease, kuru, and other degenerative brain diseases.

In four papers published in Neuron and Cell Reports, Dr. Kandel's laboratory show how prion-like proteins - similar to the prions behind mad cow disease in cattle and Creutzfeld-Jakob disease in humans - are critical for maintaining long-term memories in mice, and probably in other mammals. The lead authors of the four papers are Luana Fioriti, Joseph Stephan, Luca Colnaghi and Bettina Drisaldi.

When long-term memories are created in the brain, new connections are made between neurons to store the memory. But those physical connections must be maintained for a memory to persist, or else they will disintegrate and the memory will disappear within days. Many researchers have searched for molecules that maintain long-term memory, but their identity has remained elusive.

These memory molecules are a normal version of prion proteins, according to research led by Nobel laureate Eric Kandel, MD, who is University Professor & Kavli Professor of Brain Science, co-director of Columbia's Mortimer B. Zuckerman Mind Brain Behavior Institute, director of the Kavli Institute for Brain Science, and senior investigator, Howard Hughes Medical Institute, at CUMC.

Prions--derived from the words protein infectious particles--are a unique class of proteins. Unlike other proteins, they are not only able to self-propagate but also to induce other proteins to take on their alternative shape. When prions form in a cell, notably in a neuron, they cause damage by grouping together in sticky aggregates that disrupt cellular processes. Prion aggregates are highly stable and accumulate in infected tissue, causing tissue damage and cell death. The dying cell releases the prion proteins, which are then taken up by other cells - and are thus considered infectious. These abnormal proteins are known to cause mad cow disease (bovine spongiform encephalopathy). They also have been linked to a variety of neurodegenerative diseases, including Alzheimer's, Parkinson's, and Huntington's.

In contrast, functional prion proteins can play a physiological role in the cell and do not contribute to disease.

Kausik Si and Dr. Kandel first identified functional prions in the giant sea slug (Aplysia) and found they contribute to the maintenance of memory storage. More recently, the Kandel laboratory searched for and found a similar protein in mice, called CPEB3.

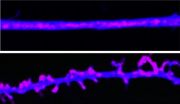

In one of many experiments described in the paper by Luana Fioriti, the researchers challenged mice to repeatedly navigate a maze, allowing the animals to create a long-term memory. But when the researchers knocked out the animal's CPEB3 gene two weeks after the memory was made, the memory disappeared.

The researchers then discovered how CPEB3 works inside the neurons to maintain long-term memories. "Like disease-causing prions, functional prions come in two varieties, a soluble form and a form that creates aggregates," said. Kandel. "When we learn something and form long-term memories, new synaptic connections are made, the soluble prions in those synapses are converted into aggregated prions. The aggregated prions turn on protein synthesis necessary to maintain the memory."

As long as these aggregates are present, Kandel says, long-term memories persist. Prion aggregates renew themselves by continually recruiting newly made soluble prions into the aggregates. "This ongoing maintenance is crucial," said Dr. Kandel. "It's how you remember, for example, your first love for the rest of your life."

A similar protein exists in humans, suggesting that the same mechanism is at work in the human brain, but more research is needed. "It's possible that it has the same role in memory, but until this has been examined, we won't know," said Dr. Kandel.

"There are probably other regulatory components involved," he added. "Long-term memory is a complicated process, so I doubt this is the only important factor.

INFORMATION:

The Neuron paper is titled, "The Persistence of Hippocampal-based Memory Requires Protein Synthesis Mediated by the Prion-like Protein CPEB3." The complete list of authors is: Eric Kandel, Luana Fioriti, Cory Myers, Yan-You Huang, Xiang Li, Joseph Stephan, Pierre Trifilieff, Stelios Kosmidis, Bettina Drisaldi, and Elias Pavlopoulos (all at CUMC).

This work was supported by grants from the Howard Hughes Medical Institute and the National Institutes of Health (R01 GM070934-06).

Three related studies, including more details about CPEB3 function, appeared in June in the online issues Cell Reports:

"SUMOylation is an Inhibitory Constraint that Regulates the Prion-like Aggregation and Activity of CPEB3." The complete list of authors is: Eric Kandel, Luana Fioriti, Cory Myers, Yan-You Huang, Xiang Li, Joseph Stephan, Pierre Trifilieff, Luca Colnaghi, Stelios Kosmidis, Bettina Drisaldi, and Elias Pavlopoulos (all at CUMC). The study was supported by grants from the Howard Hughes Medical Institute, the Italian Academy for Advanced Studies in America, and the Alexander Bodini Foundation.

"The CPEB3 protein is a functional prion that interacts with the actin cytoskeleton." The complete list of authors is: Eric Kandel, Joseph S. Stephan, Luana Fioriti, Nayan Lamba, Luca Colnaghi, Kevin Karl, and Irina L. Derkatch (all at CUMC). The study was supported by grants from the Howard Hughes Medical Institute and the National Institutes of Health (R01 GM070934-06).

"MicroRNA-22 gates long-term heterosynaptic plasticity in Aplysia through presynaptic regulation of CPEB and downstream targets." The complete list of authors is: Eric Kandel, Ferdinando Fiumara (University of Turin, Italy), Priyamvada Rajasethupathy (CUMC), Igor Antonov (CUMC), Stylianos Kosmidis (CUMC), and Wayne Sossin (McGill University, Montreal, Quebec, Canada). The study was supported by a grant from the Howard Hughes Medical Institute.

The authors declare no financial or other conflicts of interest.

***Live video: CUMC now has a fully equipped video studio capable of connecting our experts with news media anywhere in the world for live or live-to-tape interviews. For information, contact Karin Eskenazi, 212-305-3900***

Think you're a foodie? Adventurous eaters, known as "foodies," are often associated with indulgence and excess. However, a new Cornell Food and Brand Lab study shows just the opposite -adventurous eaters weigh less and may be healthier than their less-adventurous counterparts.

The nationwide U.S. survey of 502 women showed that those who had eaten the widest variety of uncommon foods -- including seitan, beef tongue, Kimchi, rabbit, and polenta-- also rated themselves as healthier eaters, more physically active, and more concerned with the healthfulness of their food ...

An infestation of speck-sized Varroa destructor mites can wipe out an entire colony of honey bees in 2-3 years if left untreated. Pesticides help beekeepers rid their hives of these parasitic arthropods, which feed on the blood-like liquid inside of their hosts and lay their eggs on larvae, but mite populations become resistant to the chemicals over time.

While exploring plant-based alternatives to control Varroa mites, Chinese bioagricultural and Japanese cell physiological labs saw that certain tick repellents repress mites from finding their honey bee hosts. In a ...

To observe the brain in action, scientists and physicians use imaging techniques, among which functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) is the best known. These techniques are not based on direct observations of electric impulses from activated neurons, but on one of their consequences. Indeed, this stimulation triggers physiological modifications in the activated cerebral region, changes that become visible by imaging. Until now, it was believed that these differences were only due to modifications of the blood influx towards the cells. By using intrinsic optical signals ...

Healthy people given the serotonin-enhancing antidepressant citalopram were willing to pay almost twice as much to prevent harm to themselves or others than those given placebo drugs in a moral decision-making experiment at UCL. In contrast, the dopamine-boosting Parkinson's drug levodopa made healthy people more selfish, eliminating an altruistic tendency to prefer harming themselves over others. The study was a double-blind randomised controlled trial and the results are published in Current Biology.

The research provides insight into the neural basis of clinical disorders ...

BETHESDA, MD - The American Society of Human Genetics (ASHG) Workgroup on Pediatric Genetic and Genomic Testing has issued a position statement on Points to Consider: Ethical, Legal, and Psychosocial Implications of Genetic Testing in Children and Adolescents. Published today in The American Journal of Human Genetics, the statement aims to guide approaches to genetic testing for children in the research and clinical contexts. It also serves as an update to the Society's 1995 statement of the same title, which was issued jointly with the American College of Medical Genetics.

"Twenty ...

Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) causes a gradual loss of respiratory capacity and can be lethal within a few years. The cause is unknown, although it can be attributed to a combination of genetics and the environment. A team of researchers from the Spanish National Cancer Research Centre (CNIO) have now discovered that telomeres, the structures that protect the chromosomes, are at the origin of pulmonary fibrosis. This is the first time that telomere damage has been identified as a cause of the disease. This finding opens up new avenues for the development of therapies ...

A mutation found in most melanomas rewires cancer cells' metabolism, making them dependent on a ketogenesis enzyme, researchers at Winship Cancer Institute of Emory University have discovered.

The finding points to possible strategies for countering resistance to existing drugs that target the B-raf V600E mutation, or potential alternatives to those drugs. It may also explain why the V600E mutation in particular is so common in melanomas.

The results are scheduled for publication in Molecular Cell.

The growth-promoting V600E mutation in the gene B-raf is present in ...

The first comprehensive analysis of the woolly mammoth genome reveals extensive genetic changes that allowed mammoths to adapt to life in the arctic. Mammoth genes that differed from their counterparts in elephants played roles in skin and hair development, fat metabolism, insulin signaling and numerous other traits. Genes linked to physical traits such as skull shape, small ears and short tails were also identified. As a test of function, a mammoth gene involved in temperature sensation was resurrected in the laboratory and its protein product characterized.

The study, ...

MAYWOOD, Ill. - New devices called stent retrievers are enabling physicians to benefit selected patients who suffer strokes caused by blood clots. The devices effectively stop strokes in their tracks.

For the first time, new guidelines from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association recommend the treatment for carefully selected patients who are undergoing acute ischemic strokes and who meet certain other conditions.

Loyola University Medical Center stroke specialist Jose Biller, MD, is a member of the expert panel that wrote the guidelines, published ...

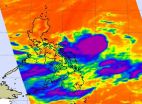

Infrared date from NASA's Aqua satellite spotted the strongest storms within newborn Tropical Depression 10W over the Philippine Sea today, July 2. It is expected to strength to a tropical storm, at which time it will be renamed "Linfa."

A tropical cyclone is made up of hundreds of thunderstorms, and the highest storms are the coldest and most powerful. To identify those areas with the strongest storms, infrared data is used because it tells temperature. The higher the cloud top, the stronger the uplift in a storm and the colder the cloud top temperature will be.

The ...