(Press-News.org) Researchers at the Hong Kong University of Science and Technology (HKUST) have found a way to stimulate the growth of axons, which may spell the dawn of a new beginning on chronic SCI treatments.

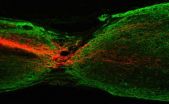

Chronic spinal cord injury (SCI) is a formidable hurdle that prevents a large number of injured axons from crossing the lesion, particularly the corticospinal tract (CST). Patients inflicted with SCI would often suffer a loss of mobility, paralysis, and interferes with activities of daily life dramatically. While physical therapy and rehabilitation would help the patients to cope with the aftermath, axonal regrowth potential of injured neurons was thought to be intractable.

No outside stimulants are needed; the growth driver lies within the neurons themselves.

Inside our DNA, in particular.

In the July 1st issue of The Journal of Neuroscience, HKUST researchers report that the deletion of the PTEN gene would enhance compensatory sprouting of uninjured CST axons. Furthermore, the deletion up-regulated the activity of another gene, the mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR), which promoted regeneration of CST axons. Axons transmit information to different neurons, muscles, and glands; as bundles they help make up nerves.

Led by Kai Liu, PhD, the study's senior author and assistant professor in life sciences at HKUST, the research team initiated PTEN deletion on mice after pyramidotomy. Similar treatment procedures were carried out on a 2nd group 4 months after severe spinal cord injuries, and a 3rd group after 12 months. The team recorded a regenerative response of CST axons in all 3 samples--showing that PTEN deletion stimulates CST sprouting and regeneration, even though the injury was sustained a long time ago.

"As one of the long descending tracts controlling voluntary movement, the corticospinal tract (CST) plays an important role for functional recovery after spinal cord injury," says Professor Liu. "The regeneration of CST has been a major challenge in the field, especially after chronic injuries. Here we developed a strategy to modulate PTEN/mTOR signaling in adult corticospinal motor neurons in the post-injury paradigm."

"It not only promoted the sprouting of uninjured CST axons, but also enabled the regeneration of injured axons past the lesion in a mouse model of spinal cord injury, even when treatment was delayed up to 1 year after the original injury. The results considerably extend the window of opportunity for regenerating CST axons severed in spinal cord injuries.

Compared with acute injury, axons face more barriers to regenerate after chronic SCI. Previously, scientists have shown that Axon retraction may further increase the distance that axons need to travel; Extracellular matrices, which become well consolidated around the chronic lesion site, also increases inhibition. Neuronal aging may also add obstacles to regrowth. In light of all of these challenges, it is indeed surprising to find that CST axons can still regenerate after 1 year.

"It is interesting to find that chronically injured neurons retain the ability to reform tentative synaptic connections," says Liu. "PTEN inhibition can be targeted on particular neurons, which means that we can apply the procedure specifically on the region of interest as we continue our research."

INFORMATION:

This study was supported in part by the Hong Kong Research Grants Council Theme-Based Research Scheme

(Grant T13-607/12R), the National Key Basic Research Program of China (Grant 2013CB530900), the Research Grants

Council of Hong Kong Special Administrative Region (Grants AoE/M-09/12, HKUST5/CRF/12R, AoE/M-05/12,

C4011-14R, 662011, 662012, 689913, and 16101414), and the Hong Kong Spinal Cord Injury Fund.

Washington, D.C. - July 2, 2015 - Male fruit flies infected with the bacterium, Wolbachia, are less aggressive than those not infected, according to research published in the July Applied and Environmental Microbiology, a journal of the American Society for Microbiology. This is the first time bacteria have been shown to influence aggression, said corresponding author Jeremy C. Brownlie, PhD, Deputy Head, School of Natural Sciences, Griffith University, Brisbane, Australia.

The research began with a discovery by University of Arizona student Elizabeth Bondy, an undergraduate ...

Astronomers are gearing up for high-energy fireworks coming in early 2018, when a stellar remnant the size of a city meets one of the brightest stars in our galaxy. The cosmic light show will occur when a pulsar discovered by NASA's Fermi Gamma-ray Space Telescope swings by its companion star. Scientists plan a global campaign to watch the event from radio wavelengths to the highest-energy gamma rays detectable.

The pulsar, known as J2032+4127 (J2032 for short), is the crushed core of a massive star that exploded as a supernova. It is a magnetized ball about 12 miles ...

MINNEAPOLIS - A new study suggests that genes may not be to blame for the increased risk of heart disease some studies have shown in people with migraine, especially those with migraine with aura. The research is published during Headache/Migraine Awareness Month in the inaugural issue of the journal Neurology® Genetics, an open access, or free to the public, online-only, peer-reviewed journal from the American Academy of Neurology. Aura are sensations that come before the headache, often visual disturbances such as flashing lights.

"Surprisingly, when we looked ...

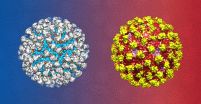

BOSTON -- A new study led by scientists at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center (BIDMC) shows that an HIV-1 vaccine regimen, involving a viral vector boosted with a purified envelope protein, provided complete protection in half of the vaccinated non-human primates (NHPs) against a series of six repeated challenges with simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV), a virus similar to HIV that infects NHPs. These findings are published online today in Science.

Based on these pre-clinical data, the HIV-1 version of this vaccine regimen is now being evaluated in an ongoing Phase ...

One more piece and we are done! A research team led by the Duke-NUS Graduate Medical School Singapore (Duke-NUS) has found the second-to-last piece of the puzzle needed to potentially cure or treat dengue. This is welcome news as the dengue virus infects about 400 million people worldwide annually, and there is currently no licensed vaccine available to treat it.

Associate Professor Shee-Mei Lok and Research Fellow Guntur Fibriansah, from the Duke-NUS Emerging Infectious Diseases (EID) Programme, led research that showed how an antibody neutralises dengue virus serotype ...

In a new Science study, Duke-NUS Graduate Medical School Singapore (Duke-NUS) scientists have identified how small changes in dengue's viral genome can affect the virus' ability to manipulate human immune defences and spread more efficiently. This research is the first of its kind that examined the dengue virus starting from broad population level observations and then linked it to specific molecular interactions, to explain an outbreak. This work provides a framework for identifying genomic differences within the virus that are important for epidemic spread.

Dengue virus ...

This news release is available in Japanese. Detailed tabletop experiments are helping researchers understand how Earth's landscapes erode to form networks of hills and valleys. The findings, which highlight a balance between processes that send sediments down hills and those that wash them out of valleys, might also help researchers predict how climate change could transform landscapes in the future. Kristin Sweeney and colleagues developed a laboratory device that mimicked the processes that smooth or disturb soil to make hillslopes, and those that cut it away to make ...

This news release is available in Japanese. Researchers have discovered that a human antibody specific to dengue virus serotype 2, called 2D22, protects mice from a lethal form of the virus -- and they suggest that the site where 2D22 binds to the virus could represent a potential vaccine target. The mosquito-borne virus, which infects nearly 400 million people around the world each year, has four distinct serotypes, or variations, and there is currently no protective vaccine available. Recent phase 3 clinical trials of a potential vaccine candidate showed poor efficacy, ...

Why is the seahorse's tail square? An international team of researchers has found the answer and it could lead to building better robots and medical devices. In a nutshell, a tail made of square, overlapping segments makes for better armor than a cylindrical tail. It's also better at gripping and grasping. Researchers describe their findings in the July 3 issue of Science.

"Almost all animal tails have circular or oval cross-sections--but not the seahorse's. We wondered why," said Michael Porter, an assistant professor in mechanical engineering at Clemson University and ...

This news release is available in Japanese. Researchers working with roses have identified an enzyme, known as RhNUDX1, which plays a key role in producing the flowers' sweet fragrances. These ornamental plants, which provide essential oils for perfumes and cosmetics, have been bred mostly for their visual traits, and their once-strong scents have faded over the generations. Restoring their fragrant odors will require a better understanding of the rose scent biosynthesis pathway. Until now, most studies of rose fragrance have focused on a biosynthetic pathway that generates ...