(Press-News.org) Researchers have long had reason to hope that blocking the flow of calcium into the mitochondria of heart and brain cells could be one way to prevent damage caused by heart attacks and strokes. But in a study of mice engineered to lack a key calcium channel in their heart cells, Johns Hopkins scientists appear to have cast a shadow of doubt on that theory. A report on their study is published online this week in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

"We confirmed that this calcium channel is important for heart function," says senior investigator Mark Anderson, M.D., Ph.D., director of the Department of Medicine at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine. "But our results also showed that this is almost certainly not going to be a good pathway to exploit in a long-term therapy, at least for heart attacks."

The experiments by Anderson and his team grew out of increased understanding in recent years of the role of calcium in heart function. With each beat of the organ, molecules of calcium whiz in and out of tiny compartments called mitochondria that are powerhouses of heart and other cells. Inside the mitochondria, calcium is generally a good thing -- it helps generate energy that the cells use to stay alive. But for almost half a century, researchers have also known that too much mitochondrial calcium can overwhelm and cause cells to die. And after a heart attack or stroke, a sudden rush of calcium into the organelles sets off this cell death pathway, leading to long-term damage.

Thus, the possibility of saving heart and brain cells by blocking this influx of calcium, Anderson says, has long been a hope, one fed a few years ago when scientists discovered the specific channel that allows calcium to pass in and out of the mitochondria, known as the mitochondrial calcium uniporter (MCU).

With the new knowledge, Anderson and colleagues set out to test the effects of blocking calcium from mitochondria by generating genetically altered mice with a mutation that disabled heart MCU function over the entire lifetime of the mice and blocked calcium flow to mitochondria in heart muscle cells.

Although almost no calcium passed into the mitochondria of their cardiomyocytes, Anderson says, their hearts still beat and developed normally. But when his team stressed the mice in a way that would normally cause an increase in heart rate, the mice's heart rates only barely rose, and their heart muscles lost efficiency, requiring extra oxygen to function.

In further experiments, when the scientists cut off oxygen to the cardiomyocytes and then restarted it -- mimicking what happens during some heart attacks -- the cells still died, even though calcium in the mitochondria clearly wasn't causing the cell death, Anderson says.

Instead, the cardiomyocytes, Anderson's group discovered, were compensating for the lack of calcium by activating other cell death pathways and turning on a host of new genes to get that job done. Blocking calcium from the mitochondria, it turned out, just changed the way the cells died after a heart attack.

"Despite the predictions that blocking this calcium channel would protect against calcium overload, it didn't protect against cell death," says Anderson. Future studies will be needed to confirm whether the same is true in brain cells, but Anderson suspects the new results will put a damper on the idea of creating drugs to block MCUs in humans requiring long-term treatments to prevent heart attacks.

INFORMATION:

Other authors on the study are Tyler P. Rasmussen, Mei-ling A. Joiner, Olha M. Koval, Biyi Chen, Zhan Gao, Zhiyong Zhu, Brett A. Wagner, Jamie Soto, Michael L. McCormick, William Kutschke, Robert M. Weiss, Liping Yu, Ryan L. Boudreau, E. Dale Abel, Fenghuang Zhan, Douglas R. Spitz, Garry R. Buettner, Long-Sheng Song and Leonid V. Zingman of the University of Iowa Carver College of Medicine in Iowa City; and Yeujin Wu, Nicholas R. Wilson, Elizabeth D. Luczak and Qinchuan Wang of the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine.

Funding for the studies described in the PNAS article was provided by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (grant numbers F30 HL114258-02, R01 HL079031, R01 HL070250, R01 HL096652, R01 HL113001); the National Institute of General Medical Sciences (grant number T32 GM007337); the National Center for Research Resources (grant number S10 RR026293-01); the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (grant number R01 DK092412); the Veterans Administration; and the Holden Comprehensive Cancer Center (grant number P30 CA086862).

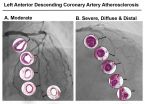

July 6, 2015 CHAPEL HILL, NC - Insulin resistance affects tens of millions of Americans and is a big risk factor for heart disease. Yet, some people with the condition never develop heart disease, while some experience moderate coronary blockages. Others, though, get severe atherosclerosis - multiple blockages and deterioration of coronary arteries characterized by thick, hard, plaque-ridden arterial walls. Researchers at the UNC School of Medicine created a first-of-its-kind animal model to pinpoint two biomarkers that are elevated in the most severe form of coronary disease.

The ...

Researchers have found several key differences among people who receive hospice care--which maintains or improves the quality of life for someone whose condition is unlikely to be cured--in assisted-living facilities (ALFs) compared with people who receive hospice care at home.

People receiving hospice care in ALFs were more likely to be older and female than people who received hospice care at home. Also, people living in ALFs enrolled in hospice care much earlier than patients living in home settings. This allowed them to receive more help from the hospice team before ...

Lyme disease is currently estimated to affect 300,000 people in the U.S. every year, and blacklegged ticks, the disease's main vector, have recently flourished in areas previously thought to be devoid of this arachnid.

A new study finds that the newly detected tick populations likely arose mainly from southern populations that migrated to nearby northern locations.

"The fine temporal and spatial scale of the samples analyzed allowed for precise estimates of the rate, timing, and direction of individual migratory events," said Dr. Camilo Khatchikian, lead author of the ...

DURHAM, N.C. -- Looking around at a 20th high school reunion, you might notice something puzzling about your classmates. Although they were all born within months of each other, these 38-year-olds appear to be aging at different rates.

Indeed they are, say the leaders of a large long-term human health study in New Zealand that has sought clues to the aging process in young adults.

In a paper appearing the week of July 6 in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, the team from the U.S., UK, Israel and New Zealand introduces a panel of 18 biological measures ...

Madison, Wis. -- In rhesus monkey families - just as in their human cousins - anxious parents are more likely to have anxious offspring.

And a new study in an extended family of monkeys provides important insights into how the risk of developing anxiety and depression is passed from parents to children.

The study from the Department of Psychiatry and the Health Emotions Research Institute at the University of Wisconsin-Madison shows how an over-active brain circuit involving three brain areas inherited from generation to generation may set the stage for developing ...

Across the entire world, women can expect to live longer than men. But why does this occur, and was this always the case?

According to a new study led by University of Southern California Leonard Davis School of Gerontology researchers, significant differences in life expectancies between the sexes first emerged as recently as the turn of the 20th century. As infectious disease prevention, improved diets and other positive health behaviors were adopted by people born during the 1800s and early 1900s, death rates plummeted, but women began reaping the longevity benefits ...

PITTSBURGH, July 6, 2015 - University of Pittsburgh Cancer Institute (UPCI) scientists recently led a panel of experts in revising national guidelines for thyroid cancer testing to reflect newly available tests that better incorporate personalized medicine into diagnosing the condition.

Their clinical explanation for when to use and how to interpret thyroid cancer tests is published in the July issue of the scientific journal Thyroid. The American Thyroid Association is revising its 2015 Guidelines for Thyroid Nodule and Thyroid Cancer Management to direct doctors to ...

Alexandria, VA - With the Internet, science and a little imagination, scientists are able to bring remote worlds to life. Dinologue.com brings the Mesozoic to life, and EARTH Magazine reviews it in the July 2015 issue.

The website was created through a partnership between Parallax Film Productions and popular science writer, and amateur paleontologist, Brian Switek. The Dinologue portal is filled with captivating articles and adventurous videos to help bring science and paleontology to the masses. Get the geoscientist's perspective of Dinologue in EARTH Magazine: http://bit.ly/1JJDy7r.

The ...

Researchers have provided a new roadmap for tackling future agricultural production issues by using solutions that involve crassulacean acid metabolism (CAM), a specialized type of photosynthesis that enhances the efficiency by which plants use water.

Plants that use CAM, which include cacti and agave, are typically found in dry environments. Increasing agricultural production to accommodate society's growing population might be achieved by developing CAM crops as new sources for food, feed, fiber, and bioenergy or by engineering non-CAM crops to use CAM strategies to ...

Putnam Valley, N.Y. (July 6, 2015) - Peripheral nerve injuries often are caused by trauma or surgical complications and can result in considerable disabilities. Regeneration of peripheral nerves can be accomplished effectively using autologous (self-donated) nerve grafts, but that procedure may sacrifice a functional nerve and cause loss of sensation in another part of the patient's body.

Searching for an alternative to autologous nerve grafts (autografts), researchers in Japan transplanted mobilized dental pulp stem cells (MDPSCs) into laboratory rats with sciatic nerve ...