Researchers at the Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania are making headway in this area by studying stem cells in their natural environment in an organism. Stem cell populations reside in areas called niches deep within different types of organs. Scientists think that these niches control stem cell behavior, that is "telling" the stem cell when to produce more stem cells or when to produce daughter cells that will be the workhorses for that tissue or organ. In addition, many niches contain different stem cell types, each necessary to produce the distinct types of cells needed for tissue renewal. But how the production of daughter cells from the different stem cell types is coordinated within a single niche is virtually unknown.

Stephen DiNardo, PhD, a professor of Cell and Developmental Biology and Kari F. Lenhart, PhD, a postdoctoral scientist in the DiNardo lab, study the development of fruit fly sperm as a model to investigate the stem cell-niche. In this case, the niche residing at the tip of the testis is the site of stem cell divisions, which are critical to produce daughter cells that later become sperm.

DiNardo and Lenhart showed that the division of these stem cells is regulated at the final stage of replication, called cytokinesis, right before the two daughter cells separate. What's more, the timing of that separation is controlled by neighboring stem cells in the niche. This striking finding shows that regulation of cytokinesis is how this niche coordinately produces daughter cells from different stem cell types. The work was published online in advance of the July 27th print publication of Developmental Cell.

Seeing is Discovering In the fruitfly testis niche, previous studies have shown that different stem cell types had to coordinate with each other. If their respective functions were uncoupled from each other, by mutation for example, the testis could not make sperm. Such coordination is an emerging theme in many tissue niches. For example, in both the blood-cell-producing and the hair-follicle niches, different stem cell types need to coordinate their individual production. But, how does such coordination come about? This is where the well-studied fruitfly testis comes in.

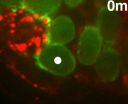

"Using high-power microscopy, we can watch individual cells and follow along with how they replicate in real time," says Lenhart. "That led us to discover something about cytokinesis in the stem cells. Normally, cytokinesis is such a fundamental cellular process that it proceeds virtually identically in all cells; but here something very odd was happening."

Through live imaging, they found that a ring comprised of the protein actin forms between the two daughter cells to block cytokinesis from proceeding. The duration of the block is controlled by another enzyme. "We have found a way by which cytokinesis is temporarily halted and later started back up, and this phenomenon coordinates all cell players in the maturation of sperm cells in this niche," says DiNardo. They also found that a non-sex cell needs to wrap itself around the sperm stem cell to promote theses final steps of cytokinesis

Step by Step Two types of stem cells exist in the fruit fly testis: One whose fate is to produce a daughter cell that matures into a full-fledged sperm cell and a daughter that stays as a stem cell (otherwise, in each division the tissue would lose a stem cell and quickly exhaust its capacity for renewal), and a second stem cell type that is a somatic, or non-sex, stem cell that similarly produces a daughter that stays as a stem cell, and another daughter that matures into a protective cell that flanks the maturing sperm cell in an encysting process. To complete the picture, two such somatic protective cells surround each maturing sperm cell, and those encysting somatic cells send signals to the sperm cell on how and when to mature.

"Without those signals --no sperm -- that's why the niche has to coordinate production from both stem cell types," explains Lenhart.

Researchers thought that the division of stem cells were coordinated to generate this trio of cells, but Lenhart found this wasn't the case at all. It was known from other studies that the sperm cell's halt in division could last much longer than expected-up to 15 hours - compared to other types of dividing cells, which typically take only two hours to complete division into two daughter cells. The Penn work added an understanding of how that delay is established and why it might exist.

She found that the cytokinesis step in replication of the sperm stem cell is normal, up to a point. The typical contractile ring, a temporary structure that physically squeezes the two daughter cells apart, gets dismantled as expected, but a new ring made of actin forms in its place. This actin ring stops the daughters from separating.

Eventually this block is reversed, the actin ring breaks down, and division is completed. She found that the "when" of cytokinesis completion is regulated by the flanking somatic cells. "We don't yet know if this type of coordination and control works in stem cell niches of other tissue types," says DiNardo. "However, with the capability to image live cells in the process of dividing, stopping, and then continuing to divide, under different conditions, the fruit fly system allows us to understand the steps necessary in this very basic process of cell biology."

Moving forward, the DiNardo lab is looking for stem cell niches in other types of tissues to see if this exquisite control also exists there.

INFORMATION:

This work was supported by the NIGMS (R01-GM60804) and an ACS Postdoctoral Fellowship (PF-13-029-01-DDC)

Penn Medicine is one of the world's leading academic medical centers, dedicated to the related missions of medical education, biomedical research, and excellence in patient care. Penn Medicine consists of the Raymond and Ruth Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania (founded in 1765 as the nation's first medical school) and the University of Pennsylvania Health System, which together form a $4.9 billion enterprise.

The Perelman School of Medicine has been ranked among the top five medical schools in the United States for the past 17 years, according to U.S. News & World Report's survey of research-oriented medical schools. The School is consistently among the nation's top recipients of funding from the National Institutes of Health, with $409 million awarded in the 2014 fiscal year.

The University of Pennsylvania Health System's patient care facilities include: The Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania -- recognized as one of the nation's top "Honor Roll" hospitals by U.S. News & World Report; Penn Presbyterian Medical Center; Chester County Hospital; Penn Wissahickon Hospice; and Pennsylvania Hospital -- the nation's first hospital, founded in 1751. Additional affiliated inpatient care facilities and services throughout the Philadelphia region include Chestnut Hill Hospital and Good Shepherd Penn Partners, a partnership between Good Shepherd Rehabilitation Network and Penn Medicine.

Penn Medicine is committed to improving lives and health through a variety of community-based programs and activities. In fiscal year 2014, Penn Medicine provided $771 million to benefit our community.