(Press-News.org) Brown dwarfs are relatively cool, dim objects that are difficult to detect and hard to classify. They are too massive to be planets, yet possess some planetlike characteristics; they are too small to sustain hydrogen fusion reactions at their cores, a defining characteristic of stars, yet they have starlike attributes.

By observing a brown dwarf 20 light-years away using both radio and optical telescopes, a team led by Gregg Hallinan, assistant professor of astronomy at Caltech, has found another feature that makes these so-called failed stars more like supersized planets--they host powerful auroras near their magnetic poles.

The findings appear in the July 30 issue of the journal Nature.

"We're finding that brown dwarfs are not like small stars in terms of their magnetic activity; they're like giant planets with hugely powerful auroras," says Hallinan. "If you were able to stand on the surface of the brown dwarf we observed--something you could never do because of its extremely hot temperatures and crushing surface gravity--you would sometimes be treated to a fantastic light show courtesy of auroras hundreds of thousands of times more powerful than any detected in our solar system."

In the early 2000s, astronomers began finding that brown dwarfs emit radio waves. At first, everyone assumed that the brown dwarfs were creating the radio waves in basically the same way that stars do--through the action of an extremely hot atmosphere, or corona, heated by magnetic activity near the object's surface. But brown dwarfs do not generate large flares and charged-particle emissions in the way that our sun and other stars do, so the radio emissions were surprising.

While in graduate school, in 2006, Hallinan discovered that brown dwarfs can actually pulse at radio frequencies. "We see a similar pulsing phenomenon from planets in our solar system," says Hallinan, "and that radio emission is actually due to auroras." Since then he has wondered if the radio emissions seen on brown dwarfs might be caused by auroras.

Auroral displays result when charged particles, carried by the stellar wind for example, manage to enter a planet's magnetosphere, the region where such charged particles are influenced by the planet's magnetic field. Once within the magnetosphere, those particles get accelerated along the planet's magnetic field lines to the planet's poles, where they collide with gas atoms in the atmosphere and produce the bright emissions associated with auroras.

Following his hunch, Hallinan and his colleagues conducted an extensive observation campaign of a brown dwarf called LSRJ 1835+3259, using the National Radio Astronomy Observatory's Very Large Array (VLA), the most powerful radio telescope in the world, as well as optical instruments that included Palomar's Hale Telescope and the W. M. Keck Observatory's telescopes.

Using the VLA they detected a bright pulse of radio waves that appeared as the brown dwarf rotated around. The object rotates every 2.84 hours, so the researchers were able to watch nearly three full rotations over the course of a single night.

Next, the astronomers used the Hale Telescope to observe that the brown dwarf varied optically on the same period as the radio pulses. Focusing on one of the spectral lines associated with excited hydrogen--the h-alpha emission line--they found that the object's brightness varied periodically.

Finally, Hallinan and his colleagues used the Keck telescopes to measure precisely the brightness of the brown dwarf over time--no simple feat given that these objects are many thousands of times fainter than our own sun. Hallinan and his team were able to establish that this hydrogen emission is a signature of auroras near the surface of the brown dwarf.

"As the electrons spiral down toward the atmosphere, they produce radio emissions, and then when they hit the atmosphere, they excite hydrogen in a process that occurs at Earth and other planets, albeit tens of thousands of times more intense," explains Hallinan. "We now know that this kind of auroral behavior is extending all the way from planets up to brown dwarfs."

In the case of brown dwarfs, charged particles cannot be driven into their magnetosphere by a stellar wind, as there is no stellar wind to do so. Hallinan says that some other source, such as an orbiting planet moving through the brown dwarf's magnetosphere, may be generating a current and producing the auroras. "But until we map the aurora accurately, we won't be able to say where it's coming from," he says.

He notes that brown dwarfs offer a convenient stepping stone to studying exoplanets, planets orbiting stars other than our own sun. "For the coolest brown dwarfs we've discovered, their atmosphere is pretty similar to what we would expect for many exoplanets, and you can actually look at a brown dwarf and study its atmosphere without having a star nearby that's a factor of a million times brighter obscuring your observations," says Hallinan.

Just as he has used measurements of radio waves to determine the strength of magnetic fields around brown dwarfs, he hopes to use the low-frequency radio observations of the newly built Owens Valley Long Wavelength Array to measure the magnetic fields of exoplanets. "That could be particularly interesting because whether or not a planet has a magnetic field may be an important factor in habitability," he says. "I'm trying to build a picture of magnetic field strength and topology and the role that magnetic fields play as we go from stars to brown dwarfs and eventually right down into the planetary regime."

INFORMATION:

The work, "Magnetospherically driven optical and radio aurorae at the end of the main sequence," was supported by funding from the National Science Foundation. Additional authors on the paper include Caltech senior postdoctoral scholar Stephen Bourke, Caltech graduate students Sebastian Pineda and Melodie Kao, Leon Harding of JPL, Stuart Littlefair of the University of Sheffield, Garret Cotter of the University of Oxford, Ray Butler of National University of Ireland, Galway, Aaron Golden of Yeshiva University, Gibor Basri of UC Berkeley, Gerry Doyle of Armagh Observatory, Svetlana Berdyugina of the Kiepenheuer Institute for Solar Physics, Alexey Kuznetsov of the Institute of Solar-Terrestrial Physics in Irkutsk, Russia, Michael Rupen of the National Radio Astronomy Observatory, and Antoaneta Antonova of Sofia University.

CHAPEL HILL, NC - The stem cells in our gut divide so fast that they create a completely new population of epithelial cells every week. But this quick division is also why radiation and chemotherapy wreak havoc on the gastrointestinal systems of cancer patients - such therapies target rapidly dividing cells. Scientists at the UNC School of Medicine and the UNC Lineberger Comprehensive Cancer Center found that a rare type of stem cell is immune to radiation damage thanks to high levels of a gene called Sox9.

The discovery, which was made in mice and published in the journal ...

Washington, DC--The Endocrine Society today issued a Clinical Practice Guideline (CPG) on strategies for treating Cushing's syndrome, a condition caused by overexposure to the hormone cortisol.

The CPG, entitled "Treatment of Cushing's Syndrome: An Endocrine Society Clinical Practice Guideline," was published online and will appear in the August 2015 print issue of the Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism (JCEM), a publication of the Endocrine Society.

Cushing's syndrome occurs when a person has excess cortisol in the blood for an extended period, according ...

Enrolling in an insurance plan under the Affordable Care Act is only the first step for consumers to be actively engaged in their health care, according to a new analysis from RAND Corporation researchers.

To understand the issues facing consumers as well as the payers, providers and support organizations who work directly with them, RAND researchers conducted phone-based interviews with insurance companies, physician groups and community support nonprofit organizations. The analysis of the interviews shows more work is necessary to support consumers past the point of ...

Kindergarteners' social-emotional skills are a significant predictor of their future education, employment and criminal activity, among other outcomes, according to Penn State researchers.

In a study spanning nearly 20 years, kindergarten teachers were surveyed on their students' social competence. Once the kindergarteners reached their 20s, researchers followed up to see how the students were faring, socially and occupationally. Students demonstrating better prosocial behavior were more likely to have graduated college, to be gainfully employed and to not have been arrested ...

TORONTO, ON - People who have inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), such as Crohn's disease or ulcerative colitis, have twice the odds of having a generalized anxiety disorder at some point in their lives when compared to peers without IBD, according to a new study published by University of Toronto researchers.

"Patients with IBD face substantial chronic physical problems associated with the disease," said lead-author Professor Esme Fuller-Thomson, Sandra Rotman Endowed Chair at the University of Toronto's Factor-Inwentash Faculty of Social Work. "The additional burden of ...

Today the nonprofit Alliance for Aging Research released a white paper, Our Best Shot: Expanding Prevention through Vaccination in Older Adults, that provides a comprehensive overview of the factors that drive vaccination underutilization in seniors and offers recommendations on how industry, government, and health care experts can improve patient compliance.

Although influenza, pneumococcal, tetanus, and shingles vaccines are routinely recommended for older adults, are cost-effective, are covered to varying degrees by health insurance, and prevent conditions that have ...

The coalescence of two black holes -- a very violent and exotic event -- is one of the most sought-after observations of modern astronomy. But, as these mergers emit no light of any kind, finding such elusive events has been impossible so far.

Colliding black holes do, however, release a phenomenal amount of energy as gravitational waves. The first observatories capable of directly detecting these 'gravity signals' -- ripples in the fabric of spacetime first predicted by Albert Einstein 100 years ago -- will begin observing the universe later this year.

When the gravitational ...

Johns Hopkins researchers say their review of 128 medical case histories suggests that financial penalties imposed on Maryland hospitals based solely on the total number of patients who suffer blood clots in the lung or leg fail to account for clots that occur despite the consistent and proper use of the best preventive therapies.

"We have a big problem with current pay-for-performance systems based on 'numbers-only' total counts of clots, because even when hospitals do everything they can to prevent venous thromboembolism events, they are still being dinged for patients ...

Women who were socially well integrated had a lower risk for suicide in a new analysis of data from the Nurses' Health Study, according to an article published online by JAMA Psychiatry.

Suicide is among the top 10 leading causes of death among middle-age women in the United States. Most of the work in the field emphasizes the psychiatric, psychological or biological determinants of suicide.

Alexander C. Tsai, M.D., Ph.D., of Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, and coauthors estimated the association between social integration and suicide using data from 72,607 ...

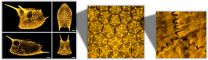

The boxfish's unique armor draws its strength from hexagon-shaped scales and the connections between them, engineers at the University of California, San Diego, have found.

They describe their findings and the carapace of the boxfish (Lactoria cornuta) in the July 27 issue of the journal Acta Materialia. Engineers also describe how the structure of the boxfish could serve as inspiration for body armor, robots and even flexible electronics.

"The boxfish is small and yet it survives in the ocean where it is surrounded by bigger, aggressive fish, at a depth of 50 to ...