(Press-News.org) A team of scientists led by Melissa Rolls, an assistant professor of biochemistry and molecular biology at Penn State University, has peered inside neurons to discover an unexpected process that is required for regeneration after severe neuron injury. The process was discovered during Rolls's studies aimed at deciphering the inner workings of dendrites -- the part of the neuron that receives information from other cells and from the outside world. The research will be published in the print edition of the scientific journal Current Biology on 21 December 2010.

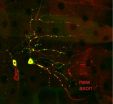

"We already know a lot about axons -- the part of the nerve cell that is responsible for sending signals," Rolls said. "However, dendrites -- the receiving end of nerve cells -- have always been quite mysterious." Unlike axons, which form large, easily recognizable bundles, dendrites are highly branched and often buried deep in the nervous system, so they have always been harder to visualize and to study. However, Rolls and her team were able to get around these difficulties. They looked inside dendrites in vivo by using a simple model organism -- the fruit fly -- whose nerve cells are similar to human nerve cells. One of the first mysteries they tackled was the layout of what Rolls referred to as intracellular "highways" -- or microtubules.

"Imagine the nerve cell with two branches -- or arms -- splayed out from it on opposite sides," Rolls explained. "Both arms have highways -- microtubules -- that run along their length and allow all the raw building materials made in the cell body to be carried to the far reaches of the cell. But the highways point in opposite directions. In axons, the growing ends -- or plus ends -- of the microtubules point away from the cell body. In contrast, in the dendrites the plus ends point towards the cell body. No one understands how a single cell can set up two different highway systems."

Unlike many other cells in our bodies, most neurons must last a lifetime. They rely on their key infrastructure -- microtubules -- to be extremely well organized, but also to be flexible so that they can be rebuilt in response to injury. Part of that flexibility comes microtubules' ability to grow constantly. Rolls and her team visualized this growth and realized that there must be a set of proteins controlling just how the highways are laid down at key intersections -- or branch points -- to keep all the microtubules pointing the same way. They identified the proteins, which include the motor protein kinesin-2, and found that when these proteins were missing the microtubules no longer pointed the same way in dendrites; that is, their polarity became disorganized.

After identifying the set of proteins required to maintain an orderly microtubule infrastructure in dendrites, the team tested whether these proteins play a role in the ability of neurons to respond to injury. Most neurons are irreplaceable, and yet they have an incredible ability to regenerate their missing parts. In earlier studies, Rolls and her team had found that, after an axon is cut off and the nerve cell no longer is able to send signals, a new axon grows from the other side of the cell; that is, from a dendrite. As part of this process, the microtubules must flip polarity. In other words, the dendrite highways must be completely rebuilt in the axonal direction. "When we disabled the flies' ability to produce the kinesin-2 protein, we found that the highways could not be rebuilt correctly, and nerve regeneration failed," Rolls explained. "Apparently, kinesin-2 is a crucial protein for polarity maintenance and for the ability to set up a new highway system when neurons need to regenerate."

Rolls also explained that visualizing how nerves maintain their intracellular highways is important for understanding neurodegenerative disease as well as response to nerve injury, which often occurs after accidents and other trauma. If the proteins that control the layout of microtubules, or carry cargo along them, do not function properly, they can become culprits in neurodegenerative diseases such as hereditary spastic paraplegia. "We hope that by showing how microtubules are built in healthy neurons and rebuilt in response to injury, our study might provide insights for future researchers who are developing drug therapies for patients with nerve disease or damage," Rolls said.

INFORMATION:

This work was funded by an American Heart Association Scientist Development Grant, a March of Dimes Basil O'Connor Starter Scholar Award, the National Institutes of Health, and a Pew Scholar in the Biomedical Sciences award to Melissa Rolls.

[ Katrina Voss ]

CONTACTS

Melissa Rolls: 814-867-1395, mur22@psu.edu

Barbara Kennedy (PIO): 814-863-4682, science@psu.edu

Key protein discovered that allows nerve cells to repair themselves

2010-12-10

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Thought for food: New CMU research shows imagining food consumption reduces actual consumption

2010-12-10

PITTSBURGH—If you're looking to lose weight, it's okay to think about eating your favorite candy bar. In fact, go ahead and imagine devouring every last bite — all in the name of your diet.

A new study by researchers at Carnegie Mellon University, published in Science, shows that when you imagine eating a certain food, it reduces your actual consumption of that food. This landmark discovery changes the decades-old assumption that thinking about something desirable increases cravings for it and its consumption.

Drawing on research that shows that perception and mental ...

Massive gene loss linked to pathogen's stealthy plant-dependent lifestyle

2010-12-10

An international team of scientists, which includes researchers from Virginia Tech, has cracked the genetic code of a plant pathogen that causes downy mildew disease. Downy mildews are a widespread class of destructive diseases that cause major losses to crops as diverse as maize, grapes, and lettuce. The paper describing the genome sequence of the downy mildew pathogen Hyaloperonospora arabidopsidis, which attacks the widely studied model plant Arabidopsis thaliana, is the cover story of this week's edition of the journal Science.

In the paper, the sequence of H. arabidopsidis ...

Cutting dietary phosphate doesn't save dialysis patients' lives

2010-12-10

Doctors often ask kidney disease patients on dialysis to limit the amount of phosphate they consume in their diets, but this does not help prolong their lives, according to a study appearing in an upcoming issue of the Clinical Journal of the American Society Nephrology (CJASN). The results even suggest that prescribing low phosphate diets may increase dialysis patients' risk of premature death.

Blood phosphate levels are often high in patients with kidney disease, and dialysis treatments cannot effectively remove all of the dietary phosphate that a person normally consumes. ...

Duchenne muscular dystrophy is ultimately a stem cell disease

2010-12-10

Researchers have long known that the devastating disease called Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD) is caused by a single mutation in a gene called dystrophin. The protein encoded by that gene is critical for the integrity of muscle; without it, they are easily damaged. But new findings in mice reported online in the journal Cell on December 9th by researchers at Stanford suggest that disease symptoms, including progressive muscle weakening leading to respiratory failure, only set in when skeletal muscle stem cells can no longer keep up with the needed repairs.

"This is ...

New mouse model for duchenne muscular dystrophy implicates stem cells, Stanford researchers say

2010-12-10

STANFORD, Calif. — For years, scientists have tried to understand why children with Duchenne muscular dystrophy experience severe muscle wasting and eventual death. After all, laboratory mice with the same mutation that causes the disease in humans display only a slight weakness. Now research by scientists at the Stanford University School of Medicine, and a new animal model of the disease they developed, points a finger squarely at the inability of human muscle stem cells to keep up with the ongoing damage caused by the disorder.

"Patients with muscular dystrophy experience ...

Adapting agriculture to climate change: New global search to save endangered crop wild relatives

2010-12-10

ROME (10 December 2010)—The Global Crop Diversity Trust today announced a major global search to systematically find, gather, catalogue, use, and save the wild relatives of wheat, rice, beans, potato, barley, lentils, chickpea, and other essential food crops, in order to help protect global food supplies against the imminent threat of climate change, and strengthen future food security.

The initiative, led by the Global Crop Diversity Trust, working in partnership with national agricultural research institutes, Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, and the Consultative Group ...

Early study analysis suggests exemestane reduces breast density in high risk postmenopausal women

2010-12-10

San Antonio, Tex. -- A drug that shows promise for preventing breast cancer in postmenopausal women with an increased risk of developing the disease, appears to reduce mammographic breast density in the same group of women. Having dense breast tissue on mammogram is believed to be one of the strongest predictors of breast cancer. The preliminary analysis from the small, phase II study was presented today at the 33rd Annual CTRC-AACR San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium in Texas.

The ongoing study at Georgetown Lombardi Comprehensive Cancer Center and the Center for Cancer ...

Charging makes nano-sized electrodes swell, elongate and spiral

2010-12-10

RICHLAND, Wash. -- New high resolution images of electrode wires made from materials used in rechargeable lithium ion batteries shows them contorting as they become charged with electricity. The thin, nano-sized wires writhe and fatten as lithium ions flow in during charging, according to a paper in this week's issue of the journal Science. The work suggests how rechargeable batteries eventually give out and might offer insights for building better batteries.

Battery developers know that recharging and using lithium batteries over and over damages the electrode materials, ...

Black holes and warped space: New UK telescope shows off first

2010-12-10

Spearheaded by the University of Manchester's Jodrell Bank Observatory and funded by the Science and Technology Facilities Council, the e-MERLIN telescope will allow astronomers to address key questions relating to the origin and evolution of galaxies, stars and planets.

To demonstrate its capabilities, University of Manchester astronomers turned the new telescope array toward the "Double Quasar". This enigmatic object, first discovered by Jodrell Bank, is a famous example of Einstein's theory of gravity in action.

The new image shows how the light from a quasar billions ...

Cholera strain in Haiti matches bacteria from south Asia

2010-12-10

BOSTON, Mass. (December 9, 2010)—A team of researchers from Harvard Medical School, Brigham and Women's Hospital, and Massachusetts General Hospital, with others from the United States and Haiti, has determined that the strain of cholera erupting in Haiti matches bacterial samples from South Asia and not those from Latin America. The scientists conclude that the cholera bacterial strain introduced into Haiti probably came from an infected human, contaminated food or other item from outside of Latin America. It is highly unlikely, they say, that the outbreak was triggered ...