(Press-News.org) If dark energy is hiding in our midst in the form of hypothetical particles called "chameleons," Holger Müller and his team at the University of California, Berkeley, plan to flush them out.

The results of an experiment reported in this week's issue of Science narrows the search for chameleons a thousand times compared to previous tests, and Müller, an assistant professor of physics, hopes that his next experiment will either expose chameleons or similar ultralight particles as the real dark energy, or prove they were a will-o'-the-wisp after all.

Dark energy was first discovered in 1998 when scientists observed that the universe was expanding at an ever increasing rate, apparently pushed apart by an unseen pressure permeating all of space and making up about 68 percent of the energy in the cosmos. Several UC Berkeley scientists were members of the two teams that made that Nobel Prize-winning discovery, and physicist Saul Perlmutter shared the prize.

Since then, theorists have proposed numerous theories to explain the still mysterious energy. It could be simply woven into the fabric of the universe, a cosmological constant that Albert Einstein proposed in the equations of general relativity and then disavowed. Or it could be quintessence, represented by any number of hypothetical particles, including offspring of the Higgs boson.

In 2004, theorist and co-author Justin Khoury of the University of Pennsylvania proposed one possible reason why dark energy particles haven't been detected: they're hiding from us.

Specifically, Khoury proposed that dark energy particles, which he dubbed chameleons, vary in mass depending on the density of surrounding matter.

In the emptiness of space, chameleons would have a small mass and exert force over long distances, able to push space apart. In a laboratory, however, with matter all around, they would have a large mass and extremely small reach. In physics, a low mass implies a long-range force, while a high mass implies a short-range force.

This would be one way to explain why the energy that dominates the universe is hard to detect in a lab.

"The chameleon field is light in empty space but as soon as it enters an object it becomes very heavy and so couples only to the outermost layer of a big object, and not to the internal parts," said Müller, who is also a faculty scientist at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory. "It would pull only on the outermost nanometer."

Lifting the camouflage

When UC Berkeley post-doctoral fellow Paul Hamilton read an article by theorist Clare Burrage last August outlining a way to detect such a particle, he suspected that the atom interferometer he and Müller had built at UC Berkeley would be able to detect chameleons if they existed. Müller and his team have built some of the most sensitive detectors of forces anywhere, using them to search for slight gravitational anomalies that would indicate a problem with Einstein's General Theory of Relativity. While the most sensitive of these are physically too large to sense the short-range chameleon force, the team immediately realized that one of their less sensitive atom interferometers would be ideal.

Burrage suggested measuring the attraction caused by the chameleon field between an atom and a larger mass, instead of the attraction between two large masses, which would suppress the chameleon field to the point of being undetectable.

That's what Hamilton, Müller and his team did. They dropped cesium atoms above an inch-diameter aluminum sphere and used sensitive lasers to measure the forces on the atoms as they were in free fall for about 10 to 20 milliseconds. They detected no force other than Earth's gravity, which rules out chameleon-induced forces a million times weaker than gravity. This eliminates a large range of possible energies for the particle.

What about symmetrons?

Experiments at CERN in Geneva and the Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory in Illinois, as well as other tests using neutron interferometers, also are searching for evidence of chameleons, so far without luck. Müller and his team are currently improving their experiment to rule out all other possible particle energies or, in the best-case scenario, discover evidence that chameleons really do exist.

"Holger has ruled out chameleons that interact with normal matter more strongly than gravity, but he is now pushing his experiment into areas where chameleons interact on the same scale as gravity, where they are more likely to exist," Khoury said.

Their experiments may also help narrow the search for other hypothetical screened dark energy fields, such as symmetrons and forms of modified gravity, such as so-called f(R) gravity.

"In the worst case, we will learn more of what dark energy is not. Hopefully, that gives us a better idea of what it might be," Müller said. "One day, someone will be lucky and find it."

INFORMATION:

The work was funded by the David and Lucile Packard Foundation, the National Science Foundation and the National Aeronautics and Space Administration. Co-authors with Müller, Hamilton and Khoury are UC Berkeley physics graduate students Matt Jaffe and Quinn Simmons and post-doctoral fellow Philipp Haslinger.

Management of boreal forests needs greater attention from international policy, argued forestry experts from the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis (IIASA), Natural Resources Canada, and the University of Helsinki in Finland in a new article published this week in the journal Science. The article, which reviews recent research in the field, is part of a special issue on forests released in advance of the World Forestry Congress in September.

"Boreal forests have the potential to hit a tipping point this century," says IIASA Ecosystems Services and Management ...

This news release is available in Japanese.

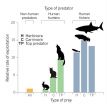

Humans are just one of many predators in this world, but a new study highlights how their intense tendency to target and kill adult prey, as well as other carnivores, sets them distinctly apart from other predators. As humans kill other species in their reproductive prime, there can be profound implications -- including widespread extinction and restructuring of food webs and ecosystems--in both terrestrial and marine systems. To evaluate the nature of human predation compared to nonhuman predation, Chris Darimont et al. conducted ...

This news release is available in Japanese.

In this special issue, the editors of Science invite experts to provide closer looks at how natural and human-induced environmental changes are affecting forests around the world, from the luscious, diverse forests of the tropics, to the pristine, resilient boreal forests of the north. The special issue is complemented by a package from Science's news department.

Amid extreme environmental and climate changes, Susan Trumbore and colleagues highlight the urgency of monitoring forest health, especially ...

This news release is available in Japanese.

Amid continued difficulties around assessing bioweapons threats, especially given limited empirical data, Crystal Boddie and colleagues took another route to gauge their danger: the collective judgment of multiple experts. The experts' opinions on bioweapons-related risks were quite diverse, the Policy Forum authors say, adding to the challenge around developing a regulatory system for legitimate dual use research. Boddie et al. explain how they employed a Delphi Method study to query the beliefs and opinions of 59 experts ...

An examination of the immune genes of the southern African Khoe-San people has revealed a completely new kind of mutation, according to researchers at the Stanford University School of Medicine. The gene variant likely contributes to healthier babies, although the variant can also lower resistance to disease.

The findings grew out of a long-term effort by Peter Parham, PhD, professor of structural biology and of microbiology and immunology, to understand how immune system genes make us reject organ transplants.

A paper detailing the findings will be published online ...

CORVALLIS, Ore. - Myriad regulations and certification requirements around the world are making it virtually impossible to use genetically engineered trees to combat catastrophic forest threats, according to a new policy analysis published this week in the journal Science.

In the United States, the time is ripe to consider regulatory changes, the authors say, because the federal government recently initiated an update of the overarching Coordinated Framework for the Regulation of Biotechnology, which governs use of genetic engineering.

North American forests are suffering ...

Are humans unsustainable 'super predators'?

Want to see what science now calls the world's "super predator"? Look in the mirror.

Research published today in the journal Science by a team led by Dr. Chris Darimont, the Hakai-Raincoast professor of geography at the University of Victoria, reveals new insight behind widespread wildlife extinctions, shrinking fish sizes and disruptions to global food chains.

"These are extreme outcomes that non-human predators seldom impose," Darimont's team writes in the article titled "The Unique Ecology of Human Predators."

"Our ...

Scientists have exposed a chink in the armour of disease-causing bugs, with a new discovery about a protein that controls bacterial defences.

Bacteria react to stressful situations - such as running out of nutrients, coming under attack from antibiotics or encountering a host body's immune system - with a range of defence mechanisms. These include constructing a resistant outer coat, growing defensive structures on their surface or producing enzymes that break down the DNA of an attacker.

The new research shows that a protein called sigma54 holds a bacterium's defences ...

WEST LAFAYETTE, Ind. -- Results of the XENON100 experiment are a bright spot in the search for dark matter.

The team of international scientists involved in the project demonstrated the sensitivity of their detector and recorded results that challenge several dark matter models and a longstanding claim of dark matter detection. Papers detailing the results will be published in upcoming issues of the journals Science and Physical Review Letters.

Dark matter is an abundant but unseen matter in the universe considered responsible for the gravitational force that keeps the ...

Scientists studying the 2009 A/H1N1 influenza pandemic have found that the inconsistent regional timing of pandemic waves in Mexico was the result of interactions between school breaks and regional variations in humidity.

The research published in PLOS Computational Biology, led by Dr. James Tamerius at the University of Iowa and Dr. Gerardo Chowell at Georgia State University, applied mathematical models to understand the social and environmental processes that generated two distinct pandemic outbreaks ("waves") in Mexico during the summer and fall of 2009.

The summer ...