(Press-News.org) CAMBRIDGE, Mass. (August 24, 2015) - By teasing apart the structure of an enzyme vital to the infectious behavior of the parasites that cause toxoplasmosis and malaria, Whitehead Institute scientists have identified a potentially 'drugable' target that could prevent parasites from entering and exiting host cells.

Although toxoplasmosis causes disease only in certain individuals-including immunocompromised patients, pregnant women, and their infants, the T. gondii parasite is closely related to Plasmodium, which causes malaria. Research on T. gondii can provide insights into Plasmodium's inner workings.

To learn more about the enzymes known as kinases, which regulate the activity of the toxoplasmosis-causing parasite Toxoplasma gondii, Whitehead Fellow Sebastian Lourido and his team enlisted an unlikely assistant: the alpaca. Unlike humans, whose antibodies have a heavy chain and a light chain, alpacas create heavy chain-only antibodies, which can be engineered into even smaller antibody fragments known as nanobodies. Alpaca nanobodies have a unique shape that allows them to reach into a protein's nooks and crannies, inaccessible to conventional antibodies.

Working with scientists from Whitehead Member Hidde Ploegh's lab, Thomas Schwartz's lab at MIT, and D.E. Shaw Research, Lourido identified a nanobody against the T. gondii enzyme CDPK1 (for "calcium-dependent protein kinase 1") that binds the kinase's regulatory domain and revealed a previously unappreciated feature of the its activation. CDPKs are essential for T. gondii and related parasites to invade and exit host cells, move, and reproduce. According to Lourido, this is one of the first times that nanobodies have been used to decipher the inner workings of an enzyme.

Conveniently, the nanobody, called 1B7, stabilizes CDPK1 in a conformation that allowed researchers in the Schwartz lab to solve the kinase's structure and describe the nanobody's interaction with the molecule. With the structure in hand, the Shaw lab created long-timescale molecular dynamics simulations of the enzyme, to model the events leading to kinase inactivation. Details of the team's work are published online this week in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS).

Structural homology between CDPKs and the calmodulin-dependent kinases (CaMKs) found in humans led to earlier assumptions that both types of enzymes are activated in a similar fashion. But the team's work shows otherwise. A CaMK is activated when a wedge holding it in an inactive state is knocked away. In contrast, Lourido likens a CDPK's active conformation to a broken arm that must be splinted in two places to maintain its integrity. When the rigid splint is removed, the kinase loses its structural ability to function. By blocking CDPK1's regulatory domain, the 1B7 nanobody inhibits the kinase by preventing the enzyme's splint from attaching.

"This work reveals something interesting about this class of enzymes," says Lourido. "It's the first time a calcium-regulated kinase has been shown to be activated in this manner. The principle that we identify is really important: we've found a new vulnerability within an enzyme that we know is extremely important to this class of parasites--including Plasmodium, the parasite that causes malaria--and is absent from humans."

Because humans lack similar kinases, drugs that target CDPKs would not affect host cells.

"The location where 1B7 binds to CDPK1 is a new drug target that people had not considered before," says Jessica Ingram, a postdoctoral researcher in Ploegh's lab and one of the lead authors of the PNAS paper. "We'd like to do some drug screens in the presence of the nanobody to see if we can find small molecules that bind in the same way. We could also look at other nanobodies against other kinases to see if this is applicable to other parasites and systems."

INFORMATION:

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health (NIH; GM103403, T32GM007287, 1DP5OD017892), U.S. Department of Energy (contract DE-AC02-06CH11357), National Science Foundation (grant 1122374), and the German Academic Exchange Service (DAAD PROMOS).

Sebastian Lourido is a Fellow of Whitehead Institute for Biomedical Research, where his laboratory is located and all his research is conducted.

Full Citation:

"Allosteric activation of apicomplexan calcium-dependent protein kinases"

PNAS, online the week of August 24, 2015

Jessica R. Ingram (1), Kevin E. Knockenhauer (2), Benedikt M. Markus (1), Joseph Mandelbaum (1), Alexander Ramek (3), Yibing Shan (3), David E. Shaw (3,4), Thomas U. Schwartz (2), Hidde L. Ploegh (1,2), Sebastian Lourido (1).

1. Whitehead Institute for Biomedical Research, Cambridge, MA 02142, USA

2. Department of Biology, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, MA

02139

3. D. E. Shaw Research, New York, NY 10036, USA

4. Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Biophysics, Columbia University, New York, NY 10032, USA

Commonly used antidepressant drugs change levels of a key signaling protein in the brain region that processes both pain and mood, according to a study conducted at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai and published August 24 in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS). The newly understood mechanism could yield insights into more precise future treatments for nerve pain and depression.

The study was conducted in mice suffering from chronic neuropathic pain, a condition which is caused in mice and humans by nerve damage. Chronic neuropathic ...

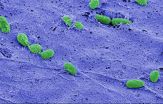

Bacteria are best known as free-living single cells, but in reality their lives are much more complex. To survive in harsh environments, many species of bacteria will band together and form a biofilm--a collection of cells held together by a tough web of fibers that offers protection from all manner of threats, including antibiotics. A familiar biofilm is the dental plaque that forms on teeth between brushings, but biofilms can form almost anywhere given the right conditions.

Biofilms are a huge problem in the health care industry. When disease-causing bacteria establish ...

Atlanta, GA - August 24, 2015 - Respiratory syncytial virus (RSV), which is the leading cause of childhood respiratory hospitalizations among premature babies, can be detected from the clothes worn by caregivers/visitors who are visiting infants in the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU), according to research being presented at the International Conference on Emerging and Infectious Diseases in Atlanta, Georgia.

"The aim of this study was to identify potential sources of transmission of RSV in the NICU to better inform infection control strategies," said Dr. Nusrat ...

Atlanta, GA - August 24, 2015 - Experts show that while Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS-CoV), a viral respiratory illness, is infecting less people, it has a higher mortality rate and affects a specific target population when compared to Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS-CoV). This research is being presented at the International Conference on Emerging and Infectious Diseases in Atlanta, Georgia.

"The research conducted in this study focuses on understanding what population of individuals are most likely to become infected by MERS-CoV, compared to the population ...

BEAUMONT -- Entomologists in Texas got a whiff of a new stink bug doing economic damage to soybeans in Texas and are developing ways to help farmers combat it, according to a report in the journal Environmental Entomology.

Various types of stink bugs have long been a problem on soybean crops, but when sweeps of fields in southeast Texas netted 65 percent redbanded stink bugs, entomologists realized this particular bug had become the predominant pest problem, according to Dr. Mo Way, an entomologist at the Texas A&M AgriLife Research and Extension Center in Beaumont.

The ...

Philadelphia, PA, August 24, 2015 - Antibiotic-resistant bacteria are a concern for the health and well-being of both humans and farm animals. One of the most common and costly diseases faced by the dairy industry is bovine mastitis, a potentially fatal bacterial inflammation of the mammary gland (IMI). Widespread use of antibiotics to treat the disease is often blamed for generating antibiotic-resistant bacteria. However, researchers investigating staphylococcal populations responsible for causing mastitis in dairy cows in South Africa found that humans carried more antibiotic-resistant ...

Cancer researchers are constantly in search of more-effective and less-toxic approaches to stopping the disease, and have recently launched clinical trials testing a new class of drugs called BET inhibitors. These therapies act on a group of proteins that help regulate the expression of many genes, some of which play a role in cancer.

New findings from The Rockefeller University suggest that the original version of BET inhibitors causes molecular changes in mouse neurons, and can lead to memory loss in mice that receive it. Published in Nature Neuroscience on August ...

Resveratrol, a compound found commonly in grape skins and red wine, has been shown to have several potentially beneficial effects on health, including cardiovascular health, stroke prevention and cancer treatments. However, scientists do not yet fully understand how the chemical works and whether or not it can be used for treatment of diseases in humans and animals.

Now, researchers at the University of Missouri have found that resveratrol does affect the immune systems of dogs in different ways when introduced to dogs' blood. Sandra Axiak-Bechtel, an assistant professor ...

In a new effort, researchers from the University of Pennsylvania and Baylor College of Medicine have used advanced imaging technology to fill in details about the underlying cause of canine diabetes, which until now has been little understood. For the first time, they've precisely quantified the dramatic loss of insulin-producing beta cells in dogs with the disease and compared it to the loss observed in people with type I diabetes.

"The architecture of the canine pancreas has never been studied in the detail that we have done in this paper," said Rebecka Hess, professor ...

Black bears in Yosemite National Park that don't seek out human foods subsist primarily on plants and nuts, according to a study conducted by biologists at UC San Diego who also found that ants and other sources of animal protein, such as mule deer, make up only a small fraction of the bears' annual diet.

Their study, published in this week's early online edition of the journal Methods in Ecology and Evolution, might surprise bear ecologists and conservationists who had long assumed that black bears in the Sierra Nevada rely on lots of protein from ants and other insects ...