(Press-News.org) This news release is available in German.

The Earth, planets, stars, and galaxies form only the visible portion of the matter in the universe. Greater by far is the share accounted for by invisible "dark matter". Scientists have searched for the particles of dark matter in numerous experiments - so far, in vain.

With the CRESST experiment, now the search radius can be considerably expanded: The CRESST detectors are being overhauled and are then able to detect particles whose mass lies below the current measurement range. As a consequence, the chance of tracking dark matter down goes up.

Theoretical models and astrophysical observations leave hardly any doubt that dark matter exists: Its share is five times more than all visible material. "So far a likely candidate for the dark matter particle was thought to be a heavy particle, the so-called WIMP," explains Dr. Federica Petricca, a researcher at the Max Planck Institute for Physics and spokesperson of the CRESST experiment (Cryogenic Rare Event Search with Superconducting Thermometers). "Most current experiments therefore probe a measurement range between 10 and 1000 GeV/c^2."

The current lower limit of 10 GeV/c^2 (GeV: gigaelectronvolt; c: speed of light) roughly corresponds to the mass of a carbon atom. However, recently various new theoretical models have been developed with the potential of solving long-standing problems, like the difference between the simulated and the observed dark matter profile in galaxies. Several of theses models hint towards dark matter candidates below the mass of the traditional WIMP.

Measurement record for light particles of dark matter

Now CRESST has achieved an important step toward tracking down these potential "lightweights": In a long-term experiment with one detector, the researchers achieved an energy threshold of 307 eV. "With that, this detector is best suited for measurements between 0.5 and 4 GeV/c^2, improving its sensitivity by 100 times," says Dr. Jean-Come Lanfranchi, scientist at the Chair for Experimental and Astroparticle Physics at Technical University of Munich.

"We now can detect particles that are considerably lighter than WIMPs - for example dark matter particles with a weight comparable to a proton, which has a mass of 0.94 GeV/c^2", adds Petricca.

On the basis of the newly gained insights, the scientists will now equip the experiment with the novel detectors. The next measurement cycle of CRESST is expected to begin at the end of 2015 and last for one to two years.

Experimental setup

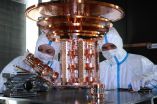

The central part of all CRESST detectors is a crystal of calcium tungstate. When a particle hits one of the three crystal atoms (calcium, tungsten, and oxygen), the detectors simultaneously measure energy and light signals from the collision that deliver information about the nature of the impinging particle.

In order to catch even the smallest possible temperature and light signals, the detector modules are cooled to near absolute zero (-273.15 degrees C). To eliminate disturbing background events, the CRESST scientists employ - for one thing - materials with little natural radioactivity. In addition, the experiment stands in the world's largest underground laboratory, in the Italian mountain Gran Sasso, and thus is largely shielded from cosmic rays.

What's new?

CRESST will work in the future with smaller and - compared to commercially manufactured materials - ultrapure crystals. With the reduced size a lower energy threshold can be achieved. These crystals are grown at the Technical University of Munich and exhibit extremely low innate radioactivity, making the experiment more sensitive.

The original bronze crystal holdings have been replaced with calcium tungstate. With this, the number of undesired effects due to natural radioactivity on the metal surfaces can be strongly reduced.

The precision of the light detector has been optimized - collisions of already known particles can be more clearly distinguished from collisions of dark matter particles.

INFORMATION:

Participants in the CRESST collaboration include the Max Planck Institute for Physics, the University of Oxford, the Technical University of Munich, the University of Tübingen, the Institute of High Energy Physics in Vienna, the Vienna University of Technology, and the Gran Sasso National Laboratory of the Istituto Nazionale di Fisica Nucleare in Italy. The work was funded by the German Research Foundation (DFG; via Cluster of Excellence Origin and Structure of the Universe), the Helmholtz Alliance for Astroparticle Physics (HAP) and the German Federal Ministry for Education and Research (BMBF).

Publication:

Results on light dark matter particles with a low threshold CRESST-II detector,

European Physical Journal C, Sept 2015

http://arxiv.org/abs/1509.01515

Washington, DC (September 8, 2015) - The modern-day complaints department tends to be a direct mention on Twitter to the company that has wronged you. It's easier than ever to have a direct line to a company, but what does a corporation get out of this interaction? A recent study published in the Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication by researchers at VU University Amsterdam, The Netherlands, found that people who follow corporate social media accounts that present a human voice are more likely to have a positive view of the company.

Corné Dijkmans (NHTV Breda ...

Sticky resin from conifers contains substances that could relieve or cure epilepsy. Researchers at Linköping University have synthesized and tested 71 substances known as resin acids, of which twelve are prime candidates for new medicines.

"Our goal is to develop some of the most potent substances into medicines," says Fredrik Elinder, professor of molecular neurobiology and head of the study, which was newly published in Nature's open-access periodical Scientific Reports.

Professor Elinder is an expert on the function of ion channels - the pores in the cell membrane ...

Individual transistors made from carbon nanotubes are faster and more energy efficient than those made from other materials. Going from a single transistor to an integrated circuit full of transistors, however, is a giant leap.

"A single microprocessor has a billion transistors in it," said Northwestern Engineering's Mark Hersam. "All billion of them work. And not only do they work, but they work reliably for years or even decades."

When trying to make the leap from an individual, nanotube-based transistor to wafer-scale integrated circuits, many research teams, including ...

Typhoon Kilo continues to thrive in the Northwestern Pacific and imagery from NASA's Terra satellite late on September 7 showed that the storm still maintained a clear eye.

The MODIS or Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer instrument that flies aboard Terra provided a visible-light image of Kilo on September 7 at 23:50 UTC (7:50 p.m. EDT). The image showed thick bands of thunderstorms wrapping around the eastern and northern quadrants of the visible eye.

At 0900 UTC (5 a.m. EDT) on September 9, Typhoon Kilo had maximum sustained winds near 65 knots (74.8 mph/120.4 ...

This news release is available in French.

Montreal, September 8, 2015 -- All countries have contributed to recent climate change, but some much more so than others. Those that have contributed more than their fair share have accumulated a climate debt, owed to countries that have contributed less to historical warming.

This is the implication of a new study published in Nature Climate Change, in which Concordia University researcher Damon Matthews shows how national carbon and climate debts could be used to decide who should pay for the global costs of climate ...

Scientists at Texas A&M University have made additional progress in understanding the process behind scar-tissue formation and wound healing -- specifically, a breakthrough in fibroblast-to-fibrocyte signaling involving two key proteins that work together to promote fibrocyte differentiation to lethal excess -- that could lead to new advances in treating and preventing fibrotic disease.

A new study led by biologists Richard Gomer and Darrell Pilling and involving Texas A&M graduate students Nehemiah Cox and Rice University technician Varsha Vakil points to a naturally ...

Contrary to popular belief, the worst injuries baseball catchers face on the field come from errant bats and foul balls, not home-plate collisions with base runners, according to findings of a study led by researchers at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine.

The research, done in collaboration with Baltimore Orioles trainers Brian Ebel and Richard Bancells, involved analysis of all catcher injuries during major league baseball games over a 10-year period.

A summary of the findings, published ahead of print Aug. 28 in the American Journal of Sports Medicine, ...

AUGUSTA, Ga. - The regular physical trauma that appears to put professional football players at risk for degenerative brain disease may also increase their risk for hypertension and cardiovascular disease, researchers say.

The frequent hits football players experience, particularly frontline defenders such as linemen, likely continually activate the body's natural defense system, producing chronic inflammation that is known to drive blood pressure up, according to a study in The FASEB Journal.

While strenuous physical activity clearly has its benefits, it also produces ...

Researchers at Southern Methodist University, Dallas, have discovered three new drug-like compounds that could ultimately offer better odds of survival to prostate cancer patients.

The drug-like compounds can be modified and developed into medicines that target a protein in the human body that is responsible for chemotherapy resistance in cancers, said biochemist Pia D. Vogel, lead author on the scientific paper reporting the discovery.

So far there's no approved drug on the market that reverses cancer chemotherapy resistance caused by P-glycoprotein, or P-gp for short, ...

Using "mini-brains" built with induced pluripotent stem cells derived from patients with a rare, but devastating, neurological disorder, researchers at University of California, San Diego School of Medicine say they have identified a drug candidate that appears to "rescue" dysfunctional cells by suppressing a critical genetic alteration.

Their findings are published in the September 8 online issue of Molecular Psychiatry.

The neurological disorder is called MECP2 duplication syndrome. First described in 2005, it is caused by duplication of genetic material in a specific ...