(Press-News.org) Researchers from Northwestern University and Yale University have developed a user-friendly technology to help scientists understand how proteins work and fix them when they are broken. Such knowledge could pave the way for new drugs for a myriad of diseases, including cancer.

The human body has a nifty way of turning its proteins on and off to alter their function and activity in cells: phosphorylation, the reversible attachment of phosphate groups to proteins. These "decorations" on proteins provide an enormous variety of function and are essential to all forms of life. Little is known, however, about how this dynamic process works in humans.

Using a special strain of E. coli bacteria, the researchers have built a cell-free protein synthesis platform technology that can manufacture large quantities of these human phosphoproteins for scientific study. This will enable scientists to learn more about the function and structure of phosphoproteins and identify which ones are involved in disease.

"This innovation will help advance the understanding of human biochemistry and physiology," said Michael C. Jewett, a biochemical engineer who led the Northwestern team.

The study was published Sept. 9 by the journal Nature Communications.

Trouble in the phosphorylation process can be a hallmark of disease, such as cancer, inflammation and Alzheimer's disease. The human proteome (the entire set of expressed proteins) is estimated to be phosphorylated at more than 100,000 unique sites, making study of phosphorylated proteins and their role in disease a daunting task.

"Our technology begins to make this a tractable problem," Jewett said. "We now can make these special proteins at unprecedented yields, with a freedom of design that is not possible in living organisms. The consequence of this innovative strategy is enormous."

Jewett, associate professor of chemical and biological engineering at Northwestern's McCormick School of Engineering, and his team worked with Yale colleagues led by Jesse Rinehart. Jewett and Rinehart are co-corresponding authors of the study.

As a synthetic biologist, Jewett uses cell-free systems to create new therapies, chemicals and novel materials to impact public health and the environment.

"This work addresses the broader question of how can we repurpose the protein synthesis machinery of the cell for synthetic biology," Jewett said. "Here we are finding new ways to leverage this machinery to understand fundamental biological questions, specifically protein phosphorylation."

Jewett and his colleagues combined state-of-the-art genome engineering tools and engineered biological "parts" into a "plug-and-play" protein expression platform that is cell-free. Cell-free systems activate complex biological systems without using living intact cells. Crude cell lysates, or extracts, are employed instead.

Specifically, the researchers prepared cell lysates of genomically recoded bacteria that incorporate amino acids not found in nature. This allowed them to harness the cell's engineered machinery and turn it into a factory, capable of on-demand biomanufacturing new classes of proteins.

"This manufacturing technology will enable scientists to decrypt the phosphorylation 'code' that exists in the human proteome," said Javin P. Oza, the lead author of the study and a postdoctoral fellow in Jewett's lab.

To demonstrate their cell-free platform technology, the researchers produced a human kinase that is involved in tumor cell proliferation and showed that it was functional and active. Kinase is an enzyme (a protein acting as a catalyst) that transfers a phosphate group onto a protein. Through this process, kinases activate the function of proteins within the cell. Kinases are implicated in many diseases and, therefore, of particular interest.

"The ability to produce kinases for study should be useful in learning how these proteins function and in developing new types of drugs," Jewett said.

INFORMATION:

The National Institutes of Health (grants NIDDK-K01DK089006 and P01DK01743341), the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (grant N66001-12-C-4211) and the David and Lucille Packard Foundation Fellowship supported the research.

The title of the paper is "Robust production of recombinant phosphoproteins using cell-free protein synthesis." The other co-first author is Hans R. Aerni, of Yale.

Alexandria, VA - In a study covered by EARTH Magazine, geoscientists identified fossils that are helping close the 15-million-year period in the fossil record known as Romer's Gap - the time from when fish showed early evidence of arms and legs until we definitively see four-legged land animals.

Scientists have been wondering for decades whether Romer's Gap exists because tetrapod fossils from that time were not preserved, or because their fossils simply have not been discovered yet. These new fossils are starting to close the gap and change the way scientists interpret ...

IVF cycles using embryos that have been frozen and thawed are just as successful as fresh embryos according to a new UNSW report.

The Assisted Reproductive Technology in Australia and New Zealand 2013 report, by UNSW's National Perinatal Epidemiology and Statistics Unit (NPESU), shows in the five years to 2013, fresh embryo IVF cycles that resulted in a baby remained stable at around 23%.

However, there has been a more than 25% increase in the birth rate for frozen embryo transfers in the last five years, rising from 18% to 23%.

The report also found a growing number ...

Patients with chronic rhinosinusitis (sinus infection) and obstructive sleep apnea report a poor quality of life, which is substantially improved following endoscopic sinus surgery, according to a study published online by JAMA Otolaryngology-Head & Neck Surgery.

A growing body of literature has highlighted the important links between quality of life (QOL), sleep, and chronic rhinosinusitis (CRS), such that disease severity has been correlated with worse QOL and patients with worse QOL have poor sleep. It is possible that CRS propagates sleep dysfunction through many ...

This news release is available in German.

The goal of brain simulations using supercomputers is to understand the processes in our brain. This is a mammoth task: the activity of an estimated 100 billion nerve cells - also known as neurons - must be represented . It is also a task that has historically been impossible because even the most powerful computers in the world can only simulate one percent of the nerve cells due to memory constraints. For this reason, scientists have turned to downscaled models. However, this downscaling is problematic, as shown by a recent ...

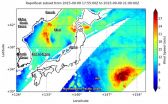

Japan has experienced large rainfall that caused flooding and large evacuations as a result of two weather systems. NASA's GPM Core satellite measured rainfall as NASA's RapidScat saw Etau and Typhoon Kilo on either side of Japan.

Over the past week Japan has experienced extreme rainfall that resulted in flooding, landslides and many injuries. A nearly stationary front that was already moving over Japan caused much of the rain but Tropical Storm Etau also interacted with the front and magnified the scale of the deluge.

Heavy rainfall led to the evacuation of over one ...

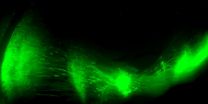

NEW YORK, NY (September 10, 2015)--Researchers have discovered why long-term use of L-DOPA (levodopa), the most effective treatment for Parkinson's disease, commonly leads to a movement problem called dyskinesia, a side effect that can be as debilitating as Parkinson's disease itself.

Using a new method for manipulating neurons in a mouse model of Parkinson's, a Columbia University Medical Center (CUMC) research team found that dyskinesia arises when striatonigral neurons become less responsive to GABA, an inhibitory neurotransmitter. This suggests that it may be possible ...

Alexandria, VA - The American Geosciences Institute's (AGI) is pleased to announce the release of a community consensus statement on access and inclusion of geoscientists with disabilities. This statement was inspired by the 2014 AGI Leadership Forum, which brought together the Executive Directors and Presidents of AGI's Member Societies to discuss the issue of access and inclusion of persons with disabilities in the geosciences.

The meeting was facilitated by the Executive Director of the International Association for Geoscience Diversity (IAGD) Christopher Atchison, ...

NASA's RapidScat instrument analyzed the sustained surface winds of Tropical Storm Henri on Sept. 8 as the storm was intensifying.

When the International Space Station flew over Tropical Depression 8 in the Eastern Atlantic Ocean on September 8 at 1p.m. EDT, NASA's RapidScat instrument aboard captured data on the storm's surface winds. RapidScat showed that there were tropical-storm-force winds north and east of the center near 27 meters per second (60.4 mph/97.2 kph). However, sustained winds on the west and southwestern quadrants were near 12 meters per second (26.8 ...

September 10, 2015 (Washington) - There are substantial differences among Americans when it comes to knowledge and understanding of science topics, especially by educational levels as well as by gender, age, race and ethnicity, according to a new Pew Research Center report.

The representative survey of more than 3,200 U.S. adults finds that, on the 12 multiple-choice questions asked, Americans gave more correct than incorrect answers. The median was eight correct answers out of 12 (mean 7.9). Some 27% answered eight or nine questions correctly, while another 26% answered ...

DOWNERS GROVE, Ill.-- September 10, 2015--Having patients lie on their left side while the right side of their colon is being examined can result in more polyps being found, thus increasing the effectiveness of colonoscopy for colorectal cancer (CRC) screening, according to a study in the September issue of GIE: Gastrointestinal Endoscopy, the monthly peer-reviewed scientific journal of the American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ASGE).

CRC is one of the most common cancers in the US and other western countries. Studies have shown that deaths from CRC are reduced ...