(Press-News.org) People with congenital stationary night blindness, or CSNB, have normal vision during the day but find it difficult or impossible to distinguish objects in low light. This rare condition is present from birth and can seriously impact quality of life, especially in locations and conditions where artificial illumination is not available.

Working in collaboration with Japanese scientists, researchers at the University of Pennsylvania have for the first time found a form of CSNB in dogs. Their discovery and subsequent hunt for the genetic mutation responsible may one day allow for the development of gene therapy to correct the dysfunction in people as well as dogs.

They reported their findings in PLOS ONE.

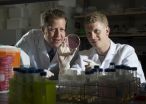

The team included the Penn School of Veterinary Medicine's Gautami Das, a postdoctoral researcher; Keiko Miyadera, an assistant professor of ophthalmology; and Gustavo Aguirre, professor of medical genetics and ophthalmology. Their main collaborator was Mineo Kondo, a professor and chair of ophthalmology at Mie University Graduate School of Medicine in Tsu, Japan, from whom they found out about a unique population of beagles with night-vision problems.

The dogs had been bred by a Japanese pharmaceutical company and displayed behaviors characteristic of night blindness.

"In bright light they can walk around and navigate easily, but in darkness they sort of freeze," Aguirre said. "It's really very dramatic."

The company enlisted the expertise of Kondo's team, which confirmed that the condition was CSNB by using physiological measures of the dogs' retinal function.

"They used a technique called electroretinography, which is what you would use as a diagnostic tool in human patients," Miyadera said. "You flash a light and you can detect the signals coming from the photoreceptors and other cells of the retina. Doing that with different light intensities and different dark and light adaptation situations helps you nail down the particular condition the dogs have."

All the affected dogs showed signs that were characteristic of CSNB, specifically a type known as Schubert-Bornschein complete CSNB, which is also seen in humans. In this condition, there is a malfunction in the process by which signals are transmitted between the retina's photoreceptor cells and bipolar cells.

The Japanese investigators first evaluated the dogs' pedigree to determine how the condition was inherited and found it was an autosomal recessive disease; in other words, a dog needs two copies of the mutated gene in order to be affected. This process also allowed the scientists to see which of the dogs was a carrier for the disease.

Kondo reached out to Aguirre's research group to delve deeper into the molecular underpinnings of the disease and to attempt to find a genetic cause.

Because the inheritance pattern they observed in the dogs is characteristic of several forms of human night blindness, the scientists examined genetic markers in both night-blind and carrier dogs to see if they had mutations in genes that also cause the disease in affected humans. But their analysis failed to turn up any matches with the human conditions; still, this allowed them to rule out 11 candidate genes and two other functionally relevant genes.

Continuing the search for a responsible gene, the Penn Vet researchers also examined affected, carrier and normal dogs for expression patterns of genes involved in the function of cones, rods, photoreceptor synapses and several key elements responsible for communication between photoreceptor and the retinal ganglion cells. Again, they failed to turn up clear patterns to indicate which gene was responsible for the condition.

They did, however, find a distinct pattern between affected, carrier and normal individuals when they used protein markers that labeled the synaptic end of the photoreceptor cells. Affected individuals had reduced labeling compared to carrier individuals, which in turn had reduced labeling compared to the control dogs.

"We often find with a disease where we have a loss of function that, even without a loss of cells, proteins and receptors may redistribute to different locations," Aguirre said.

The gene responsible for these dogs' condition remains a mystery, but the researchers believe a genome-wide approach by means of whole-genome sequencing will narrow their hunt. The scientists are excited about this possibility, as the gene may represent a novel one not previously associated with CSNB, or a new manner in which the mutation can cause disease.

"It could be that the mutation is in a regulatory region of the unidentified gene, such as within an intron or the promoter," Das said.

Once they find it, they can begin development of a gene therapy approach to treating the condition, a strategy found successful by Aguirre's group multiple times in dogs.

And this could find application in humans as well.

"The good news about this condition is that it is not progressive," Miyadera said. "You have all the cells there that you need to treat."

INFORMATION:

Additional authors on the paper included Evelyn Santana of Penn Vet; Kumiko Kato and Masahiko Sugimoto of Mie University; Ryoetsu Imai, Tomio Nakashita, Miho Imawaka, Kosuke Ueda and Hirohiko Ohtsuka of Takeda Pharmaceutical Co.; Kazuhiko Sakai and Takehiro Aihara of Kitayama Labes Co.; Shinji Ueno of Nayoga University; and Yuji Nishizawa of Chubu University.

The research was supported by the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology of Japan; the National Institutes of Health; the Foundation Fighting Blindness; Hope for Vision; and the University of Pennsylvania Vision Research Center.

A new study from the Gladstone Institutes shows for the first time that impairments in mitochondria--the brain's cellular power plants--can deplete cellular energy levels and cause neuronal dysfunction in a model of neurodegenerative disease.

A link between mitochondria, energy failure, and neurodegeneration has long been hypothesized. However, no previous studies were able to comprehensively investigate the connection because sufficiently sensitive tests, or assays, were not available to measure ATP (the energy unit of the cell that is generated by mitochondria) in individual ...

WASHINGTON (Sept. 14, 2015) -- According to initial results of a multi-site landmark study, led by Dominic Raj, M.D., at the George Washington University (GW) site, cardiovascular disease morbidity is significantly reduced through intensive management of high blood pressure.

By targeting a blood pressure of 120 millimeters of mercury (mm Hg), lower than current guidelines, researchers found that adults 50 years and older also significantly reduced their rates of cardiovascular disease and cardiovascular events, such as heart attack and heart failure, as well as stroke, ...

Humans are extremely choosy when it comes to mating, only settling down and having kids after a long screening process involving nervous flirtations, set-ups by friends, online matchmaking sites, awkward dates, humiliating rejections, hasty retreats and the occasional lucky strike. In the end, we "fall in love" and "live happily ever after." But evolution is an unforgiving force - isn't this choosiness rather a costly waste of time and energy when we should just be "going forth and multiplying?" What, if anything, is the evolutionary point of it all? A new study may have ...

MRSA is bad news. If you've never heard of it, here's what you need to know: It's pronounced MER-suh, it's a nasty bacterial infection and it can cause serious disease and death.

Senior molecular biology major Jacob Hatch knows MRSA as the infection that took his dad's leg.

Hatch was thousands of miles away on an LDS (Mormon) mission when Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus decalcified the bones in his dad's foot and lower leg, leading to an emergency amputation just below the knee.

"It was really hard to hear the news--you never expect to hear someone in ...

Irvine, Calif., Sept. 14, 2015 -- University of California, Irvine researchers with the School of Medicine have identified the mechanism by which valproic acid controls epileptic seizures, and by doing so, also revealed an underlying factor of seizures.

Valproic acid is widely used to treat various types of seizure disorders, but to this point, the cellular mechanism affected by its anticonvulsant properties were not well understood.

Dr. Naoto Hoshi, an associate professor of pharmacology and physiology & biophysics, and colleagues discovered that valproic acid preserved ...

Athens, Ga. - Microbiology researchers at the University of Georgia studying a soil bacterium have identified a potential mechanism for neurodegenerative diseases.

A role for the protein HSD10 had been suspected in patients with Alzheimer's disease and Parkinson's disease, but no direct connection had previously been established. This new breakthrough suggests that HSD10 reduces oxidative stress, promotes cell repair and prevents cellular death.

The authors first discovered that an enzyme related to HSD10, CsgA, produces energy during sporulation in the bacterium ...

A new review has produced the most conclusive evidence to date that people consume more food or non-alcoholic drinks when offered larger sized portions or when they use larger items of tableware. The research, carried out by the University of Cambridge and published in the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, suggests that eliminating larger-sized portions from the diet completely could reduce energy intake by up to 16% among UK adults or 29% among US adults.

Overeating increases the risks of heart disease, diabetes, and many cancers, which are among the leading causes ...

Single grandparents raising grandchildren are more vulnerable to poor physical and mental health than are single parents, according to a study recently published in Current Gerontology and Geriatrics Research.

These caregivers may be at greater risk for diminished physical capacity and heightened prevalence of depression, researchers found.

Researchers at Georgia State University and the University of Toronto found that solo grandparents caring for grandchildren fare worse than single parents across four critical health areas: physical health, mental health, functional ...

SAN FRANCISCO--After analyzing the seismic waves produced by small underground chemical explosions at a test site in Vermont, scientists say that some features of seismic waves could be affected by the amount of gas produced in the explosion.

This unexpected finding may have implications for how scientists use these types of chemical explosions to indirectly study the seismic signal of nuclear detonations. Researchers use chemical blasts to learn more about the specific seismic signatures produced by explosions--which differ from those produced by earthquakes--to help ...

A new guideline that aims to prevent fractures in residents of long-term care facilities is targeted at frail seniors and their families as well as health care workers. The guideline, published in CMAJ (Canadian Medical Association Journal), was developed with input from residents of long-term care facilities and their families, as well as researchers and health care professionals.

Seniors living in long-term care homes have a two- to four-fold risk of sustaining a fracture such as a hip or spinal fracture, compared with adults of similar age living in the community. ...